How Germany used “neo-liberal reforms” to beggar its neighbours and continues to push the eurozone over the brink.

Translated and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

Hartz IV (the German neo-liberal labour market reforms of 2002) was a “blessing” according to the German magazine Der Spiegel (here in German). The editor quoted a professor of economics at the University of Regensburg, who also works for the IAB (Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung) in Nuremberg, on the subject. That’s a fortunate coincidence, because last week I was invited to the University of Nuremberg to discuss this topic with a professor from the same faculty there. And, what a surprise, I heard exactly the same theses as the professor from Regensburg had given Spiegel. They deal with the effects of labour market reforms and examine, for example, the so-called “matching efficiency” on the labour market, i.e. the question whether vacancies and job seekers found each other faster after the reforms than before?

However, this is a problematic approach when it comes to an overall political assessment of the effects of Hartz IV. Like all these analyses, it is based on the assumption that a ceteris paribus (all else unchanged) clause applies: one simply assumes that nothing important has happened except for the Hartz reforms during the period under study. This overlooks, however, the fact that the Hartz reforms considerably intensified a development that had already been planned since the end of the 1990s and which tended to increase wages in Germany far less than would have been necessary from the point of view of productivity development. At that time, even the trade unions, which “reserved productivity gains for employment” (see here a tribute from that time in German), signed this choice of words within the framework of an Alliance for Jobs in 1999. If such a measure as Hartz IV is to be empirically investigated, the effects of the reform as such cannot and must not be separated from the effects of the whole complex, in which the Hartz reforms were embedded.

Why the thesis of Hartz IV as a “blessing” lies far from reality can be easily demonstrated by doing what economists should be doing, i.e. including in the analysis all effects – national and international – that were triggered or reinforced by such an institutional change as Hartz IV. But international influences do not occur at all in the studies (or in interviews) of German economists. This is never justified in a highly interconnected world economy, but in a monetary union like the one we have in Europe for twenty years, it is reckless.

If someone had asked me in 1995 how Germany’s attempt to reduce its wages (or increase them less compared to productivity growth) within the framework of the European Monetary Union, would have worked, the answer would have been very simple. I would have said that if the other nations were to accept German wage dumping without countermeasures or even increase their wages more than would be justified by their respective productivity, Germany would undoubtedly experience an export boom and exceptionally good economic development. I would also have said, however, that such a policy would bear the seeds of the destruction of European Monetary Union and would have catastrophic consequences for Germany in the longer term.

To adequately evaluate Hartz IV, it must be viewed in the overall constellation that existed in Germany and Europe at the time of wage determination. Hartz IV was only the last element of a policy aimed at pushing wage development below the level that corresponds to what we call the golden wage rule, i.e. the increase resulting from the productivity trend plus the politically set target inflation rate. Hartz IV has considerably weakened the bargaining power of trade unions because the willingness of workers to support receiving higher wages is diminished by the threat of quickly falling to the level of social welfare in the event of unemployment. The individual employee simply accepts that his fight for higher wages can very quickly end in personal disaster.

The consequences of the “Agenda 2010”

The core problem in the scientific investigation of the labour market reforms implemented by Social Democrat- Green coalition after 2000 lies in the one-sided orientation of the economy. Many economists in Germany have adopted a simple argumentation with which they have defended German policy since the beginning of monetary union: If, as in Germany with the help of Agenda 2010 (a series of neo-liberal reforms planned and executed by the Social Democrat – Green coalition at that time, which aimed to reform the German welfare system and labour relations), a (relative) reduction in wages (compared to wages in other nations) could be achieved and after twenty years of more employment, less unemployment, and a strong position in Europe, this German policy must simply have been the right one.

This simple narrative seems to justify Agenda 2010 over and over again, and the German media are uncritically following it. In the SPD, at least some in the new leadership have understood that serious mistakes in the agenda urgently need to be corrected. But they are oblivious of the decisive European dimension as well. In combination with Merkel’s conservative Christian Union parties, which are the biggest fans of Agenda 2010, it is unlikely that there will be even a single voice of weight in the federal cabinet that would be able to really come to terms with history.

Many economic analyses in this context suffer from the fact that they are based on the conditions of a relatively closed economy and on an economy linked to the rest of the world by a system of flexible exchange rates. Germany, however, was already a relatively open economy at the beginning of its wage-cutting ‘experiment’ and, over the years and as a result of wage moderation, became an extremely open economy, i.e. an economy with an extremely high export share. Germany is also a member of a large monetary union, the Euro, i.e. it operates under foreign trade conditions that are diametrically opposed to the model of flexible exchange rates. Analyses that do not take this into account in the first place cannot therefore provide any serious insight.

What exactly happened in reality? With relatively normal productivity growth, the rise in German real wages in the first ten years of the century remained very close to zero. The deliberate and politically orchestrated wage restraint in Germany created growing scope for German companies to either reduce prices in order to gain market share from their other trading partners in foreign trade (also on third markets, not only within the Monetary Union) or to achieve considerably higher profits at unchanged prices than companies in the EMU countries with “normal” wage developments.

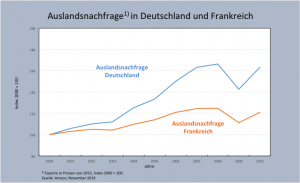

As far as exports are concerned, Germany thus outperformed all other European partners by a wide margin, as shown in Figure 1, using France as an example. German exports literally exploded in 2006 and 2007, as well as after the financial crisis. Germany was able to maintain its global market share despite emerging competition from China, while Italy and France fell far behind. The share of exports in Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) rose dramatically and now stands at almost 50 percent.

Figure 1: Foreign Demand for Germany and France from 2000

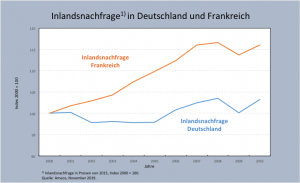

However, as Figure 2 shows, the price for wage moderation was a weak German domestic demand, as private households in Germany responded as expected to their significantly worsened income prospects by restricting their consumption. Private consumption remained extremely weak for a long time and adapted almost perfectly to the stagnation in real hourly wages.

Figure 2: Domestic Demand for Germany and France from 2000

This resulted in a split economic development rarely seen in history. While exports took off, domestic demand was stagnant and did not recover until after 2010. It then rose roughly at the same rate as France, which means that the level gap in domestic demand between the two countries remains large.

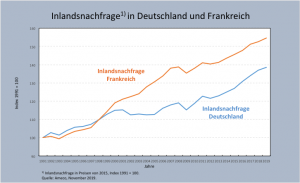

Figure 3: Domestic Demand for Germany and France from 1991

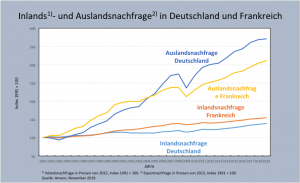

If we compare domestic and foreign demand from 1991 onwards (Figure 4), we can see the enormous gap that has arisen between German and French foreign demand and between German domestic demand and German foreign demand.

Figure 4: Domestic and Foreign Demand for Germany and France from 1991

The solution to the riddle

These simple empirical results contain the key to solving the mystery of the “success” of the neo-liberal Agenda 2010 programme: there has not been one channel through which wage cuts affect goods and labour markets, but there are always two completely different channels: the internal market channel and the export channel. The first was a disaster – not least for the prevailing doctrine – the second resulted in Germany’s apparent success story.

The fact that the expected domestic economic effects did not occur can be seen from the fact that domestic demand did not increase. The neoclassical idea of eliminating unemployment by wage reduction or wage moderation is based on the idea that, in the event of a wage reduction (or even of real wages falling short of productivity), companies begin to restructure their production processes by making greater use of the now (relatively) cheaper labour and thus replacing the relatively more expensive capital (the price of which has not changed). The “hope” is that this substitution of capital by labour will tend to lower labour productivity or increase it more slowly, so that there will be no more or at least less rationalisation-related redundancies.

This idea of substitution is completely unrealistic for various reasons. If this theory is valid, it should be possible to see over time that productivity increases less than in comparable countries that have not applied wage restraint. This is not the case in comparison to France. In Germany, productivity continued to rise at a pace very similar to that before the de facto wage reduction and that of France, where there had been no wage moderation. However, if productivity continues to rise, as in Germany, it is clear from the outset that the substitution thesis cannot be empirically proven. The fact that employment has increased without domestic demand growing in line with it can only be explained by the rise in foreign demand.

Moreover, if neoclassical economics were to make a contribution to explaining reality, it must be observed that a reduction in wages would immediately be fully offset by positive employment effects. If real wages per hour – instead of rising by two percent – stagnate, employment (the number of hours worked) would have to increase immediately by two percent. Only in this case would the overall real wage bill remain the same and, consequently, only in this case would a negative domestic demand effect be ruled out.

However, if there is a negative demand effect, the total positive employment effect of wage moderation expected by the neoclassical economists will be overturned. This is because companies act quite differently than expected by the neoclassical model, when demand falls almost simultaneously with the fall in wages. That this is the case is obvious irrespective of the rationalisation effect, because when wages are cut, the workers immediately adjust to their new situation, i.e. adapt their demand to the reduced income prospects. Although the company then pays lower wages than would otherwise have been the case, it also has a lower utilisation of its capacities.

This means that in an economy like the German one, where productivity has continued to rise despite wage moderation but domestic demand has increased less than productivity, the neoclassical effect has definitely not materialised. Thus wage moderation was a failure, no matter what else happened. Consequently, only the export channel remains, which has made the country “successful” (as measured by labour market statistics) despite relatively lower wages.

What would have happened without the “reforms”?

If domestic demand had not been constrained in Germany, but hourly wages had been allowed to follow productivity, domestic demand would have been stronger and the ensuing European economic and financial chaos would not have followed. German exports, and with them the German export surpluses, would never have gone through the roof as they did, and the foreign debt of the EMU partner countries would never have been as high as it has been. Moreover, the partners would be much less dependent on the “debt policy” of the state, which is outlawed in Europe under German „guidance“.

There can be no doubt that an already open economy that succeeds in massively undercutting its neighbours in a monetary union will sooner or later benefit from this in the form of current account surpluses if its neighbours do not oppose it in time. We know, however, that these successes will not last. Because the neighbours will sooner or later have to declare bankruptcy or adopt a similar policy; there is nothing to be gained in the long term from the wage-cutting strategy.

The opposite is the case and we can now clearly see it in Europe: In the longer term, the adjustment process will be very expensive, even for the first wage cutter. Because the wage cuts that the deficit countries are forced to decrease their demand, so that demand for the products of the first wage cutter also decreases. And this is now sitting on a dangerous economy, because of its extremely export-oriented structure. The fact that the German export and car-production dependent structure is also fatal with regard to the universally recognised requirements of climate protection makes the situation even more dramatic for Germany.

So the overall conclusion remains simple: the wage reduction strategy is not successful either in terms of growth or jobs, because it only works through the unsustainable export channel. Anyone who wants to create sustainable employment must ensure a dynamic development of demand within the economy of a country itself. If productivity then rises with capital expenditure on property, plant, and equipment, wages will have to rise so strongly that the demand dynamic in the eyes of companies is strong enough that investments that go far beyond the current utilisation of capacities are also worthwhile. Then additional jobs will be created with which existing unemployment can be reduced.

The Agenda policy did not achieve that, but only chose the primitive path of exporting unemployment to neighbouring countries. And that, one should never forget, was only possible because of recent monetary union in Europe. If Germany still had the Deutschmark, it would have been revalued sooner or later and the Hartz “success” would have terminated quickly.

What follows?

In order to counter the centrifugal forces in Europe, Germany must lead the way by withdrawing its reforms and normalising wage developments. On the other hand, Germany would undoubtedly be hit hard economically in an exit scenario of Italy or France. It would have to reckon with its production structure, which is extremely export-oriented and which was formed in the years of monetary union, being subjected to a hard adjustment. The German recession is already showing how susceptible the country is to exogenous shocks.

The basic decision in favour of the euro can still be justified today with good economic arguments. The dominant economic theory, however, has ignored these arguments from the outset and politically disavowed them. Built on monetarist ideas in the European Central Bank and crude ideas about competition between nations in the largest member state, the monetary union could not function. All those who want to save Europe as a political idea must now realise that this can only be achieved with a different economic theory and a different economic policy that follows from it. Only if the participation of all members of society in economic progress is guaranteed under all circumstances and the competition of nations is abandoned can the idea of a united Europe be saved.