Time and again in the German and European media the story is told that the problem with Germany’s current account surpluses is no longer relevant as its surplus with countries of the EMU disappeared. According to many observers this is proof positive that German trade surpluses do not harm the European economy and that they certainly have no bearing on the euro crisis. I want to take this opportunity to, once again, present some facts.

In Germany, the German Bundesbank is responsible for statistics on the balance of payments. Only the Bundesbank publishes comprehensive data regarding these balances (the balance of payments is indeed a balance: the side of goods and the side of capital must always be in balance). There has never been an even balance between Germany and the other euro area countries in the trade of goods and services (special trade refers to the so-called ‘additions to trade in goods’).

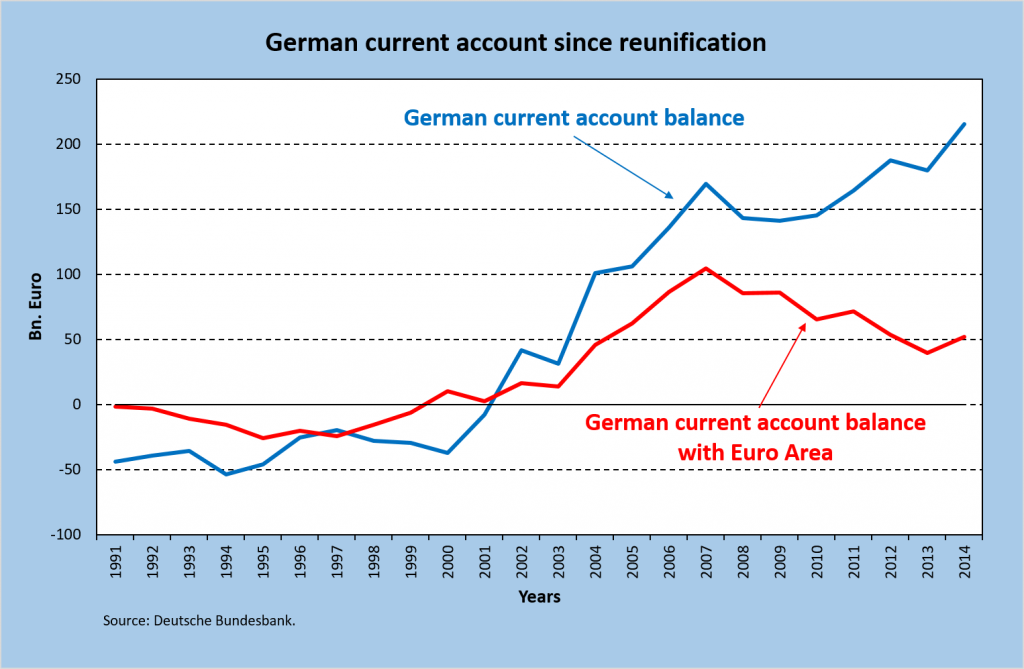

Figure 1 shows the current account balances of Germany with the world and with the other EMU countries from 1991 onwards. It is clear that the German current account surplus with the euro area begins to shrink at the start of the global crisis in 2008. It had been cut in half by 2014 compared to 2007, to just over 50 billion euros. In 2013, it was 40 billion euro – the lowest point. After 2013, the surplus started to rise again. The figures for the first three quarters of 2015 show a strong increase compared to the first three quarters of 2014 (50 billion euro to 30 billion euro).

Figure 1.

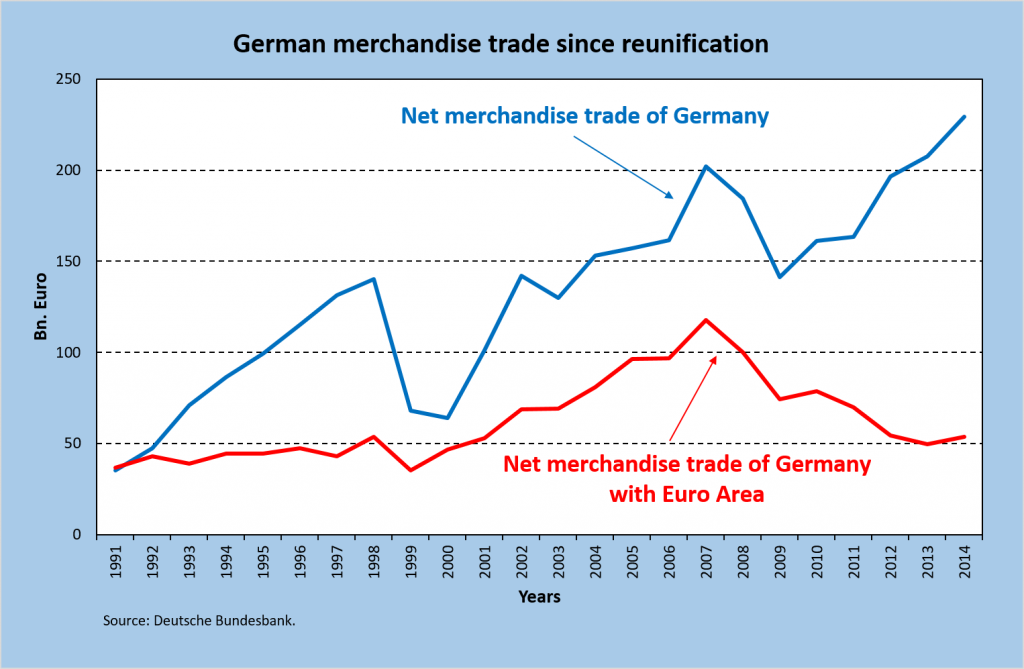

Figure 2 gives shows the trade of goods only. The figures leave out the transfer of incomes, either from labour or from capital. It also leaves out services. The pattern in recent years is quite similar to the evolution seen in Figure 1. The volume of trade in goods falls by more than 100 billion euro to about 50 billion euro in 2013 and 2014.

Figure 2.

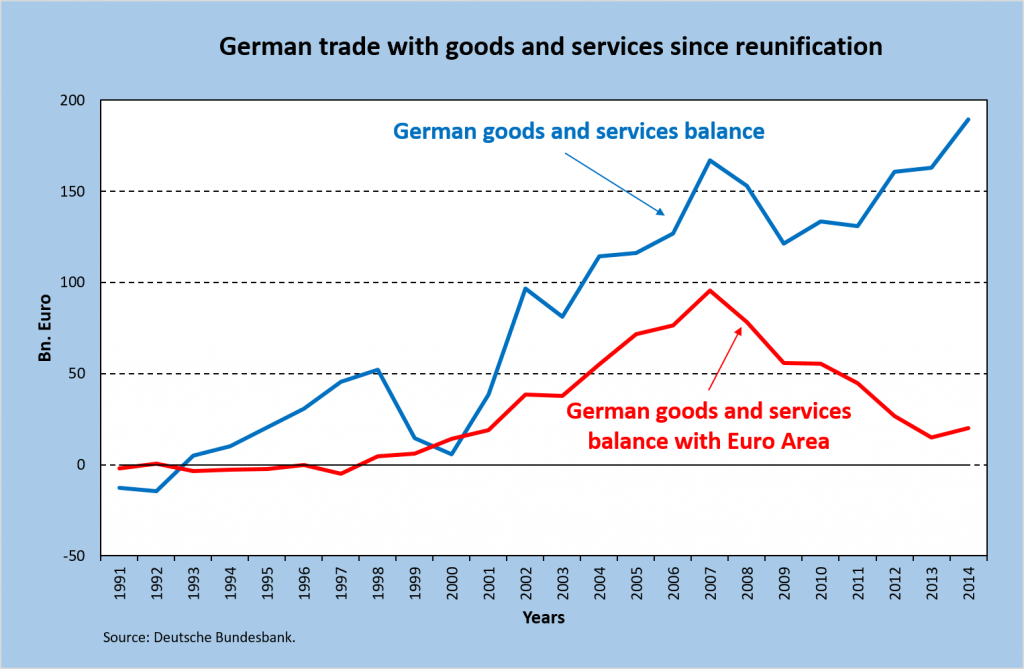

Figure 3 shows the balance of German goods and services according to the Bundesbank. Here the surplus falls even more, to 15 billion euro in 2013. After 2014, it slowly rises again. There is an increase in the first quarter of 2015 compared to the first quarter of 2014. All of this shows that there is no such thing like a balanced foreign trade balance with the euro partners. The special trade that some people refer to to make the point about balanced trade comprises only a specific part of the German trade in goods. It is an inaccurate measure of the total trade balance. The special trade figures massively overestimate German imports from the EMU. In 2014, the figures of the monthly statistics of the Bundesbank with regards to special trade and the so-called general trade were approximately 50 billion euro lower than the figures of the statistics office. (This enormous discrepancy may have to do with subcontracting processes and with different accounting methods for exports and imports in special trade.)

Figure 3.

The totals shown in Figure 3 prove that there is a marked decrease in the German surplus with the euro area. The decrease coincides with the long-lasting recession within the euro area. German trade relations with the rest of the world developed completely differently. The rest of the world also suffered from the crisis of 2008 – 2009. The German export surplus of goods and services with the rest of the world also fell (compare the figure of 2007 with the one of 2009). However, the German trade surplus with the rest of the world fell much less than the surplus with the EMU in the same period (i.e. about 6 billion euros compared to 40 billion euros).

The blue line in the figures shows that while the German surplus with the world rises the surplus with the euro area continues to fall. The net demand for German goods from the rest of the world (excluding the euro area) compensates for the decline in net demand from the EMU partners and is still growing (see the blue line in Figures 2 and 3).

This shows something extremely important that many overlook or refuse to recognise. Countries outside the euro zone relatively quickly recovered from the financial crisis, otherwise their demand for imports would not have increased to the advantage of Germany. But the euro zone did not recover. Instead, in Europe the crisis deepened. Within the EMU, an economic crisis in addition to the consequences of the financial crisis originated. This is a crisis that we only have to thank ourselves for. Europe failed to recover from the Great Recession of 2008 – 209 because austerity and wage moderation nullified any attempts to reboot the European economy. This is the fundamental problem. Frankly, the decline of the German trade surplus with the euro area is not that important. What is important, and indeed, essential, is that the trading conditions did not normalise within the EMU. As long as this is the case, the European economy cannot recover.

The euro zone can only start growing again when the rise in German surpluses comes to an end. Only then could one say that something has changed ‘structurally’ for the better. This can only happen if a ‘structural’ change in unit labour cost ratios takes place within the EMU, in concrete terms, when German wage moderation comes to an end and German unit labour costs equalise with those of the two other big EMU partners, France and Italy. If this would happen, we can even foresee a situation where the heavily indebted EMU partners could start repaying their debts. For the moment, this is not even imaginable.

Unless an equalisation (or near equalisation) of unit labour costs takes place, there is no hope for a real reversal in the direction of the flow of goods. Many stubbornly refuse to understand this. It seems counter intuitive to them, wrong, even bizarre: why give up a dominant economic position? Is accumulating trade surpluses not what economics is all about? But this is completely wrong. It is easy to present misguided figures to the German public. It is unlikely that they will be questioned, especially since what is being presented is completely in tune with widespread common prejudices and dominant ideological belief (‘the crisis countries are to blame for their own economic performance and it is they who need to adjust, not us’).

Part two will show to what extent falling imports in the deficit countries were responsible for falling deficits.