Flassbeck-economics analyses the European economy every month in detail and gives its view on the state of the cycle and the economic policies that should be adopted. We are covering a wide range of indicators and countries (the UK will be included in the future). Our skepticism concerning the European recovery and the ability of the European economy to escape the straightjackets of the European Stability Pact has proved to be absolutely right. Today, the European economy is facing the worst crisis since the Great Depression and there is no easy way out. Europe is blocked by austerity and mercantilism, the origin of both is Germany.

You will perhaps not believe this, but ‘economic experts’ working for ‘think tanks’ promote the view that the German economy is booming (or at least only very slightly sputtering), although all the official figures only show a ‘moderate growth.’ Among the indicators that these ‘experts’ use – rather than official, relevant and valid figures – are booming stock markets and the optimism of ‘insiders’ which shows up in surveys. Quite unlike us, these ‘experts’ believe that the official figures and forecasts are too low (see here). The explanation of all of this is straightforward: these analysts take a few hard numbers that they fail to interpret correctly and they blindly and wrongly believe that their so-called sentiment indicators explain reality.

One must never forget, the aim of producing such surveys is to make money. Money can only be made if these ‘experts’ manage to conceal how irrelevant their surveys really are. This is systematically made easier for them by the ‘market,’ in reality the financial markets. Financial markets are constantly craving ‘information’ on future developments. The trick is to get new information before anyone else. Whether the data are valid for the purposes of a serious forecast or analysis is besides the question. The important issue is that financial market actors try to anticipate how markets will react five minutes after the publication of a survey. It gives them a very short term advantage. This is how a lot of money is being made these days.

For example, the so-called Markit-index for the manufacturing sector in Germany stood at over 50 for many months by now, meaning that there is expansion according to the ‘official’ interpretation, although, as we have shown over and over again and show again here, that there has been no expansion whatsoever since 2011 in this area.

It would not be necessary to take the games of the financial markets seriously, if it were not for the deplorable fact that more and more journalists uncritically accept such indicators and forecasts. Journalists also increasingly use financial economists as expert sources on macroeconomic developments. But financial economists look at data from a completely different angle than macroeconomic analysts do: they look at it from the point of view of financial markets only. The end result is that a picture of economic development is being produced and presented that is fundamentally at odds with reality. And, perversely, this, in fact, constitutes an advantage to those who produce these fallacious analyses: their work makes it easy for policy-makers to conceal their misunderstandings and their blatant blunders.

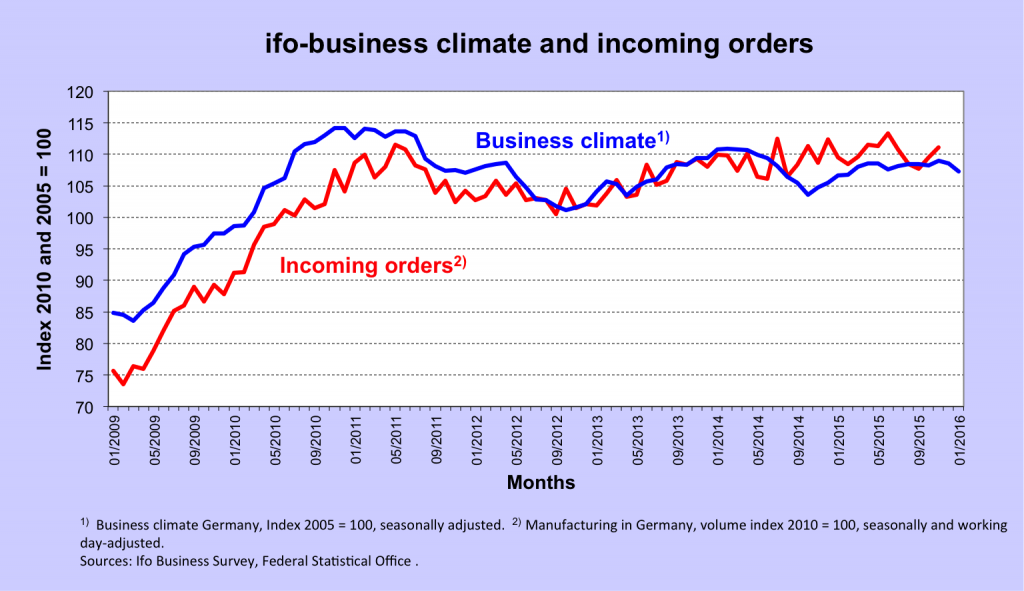

In reality, in Germany stagnation continues. The slightly weakening trend is being confirmed by the new figures (we showed the stagnation in our cyclical analyses in many reports of previous months). Figure 1 shows the ifo index, which, unlike the above-mentioned indicators inspires a certain degree of confidence. However, recently (in January) the index weakened. Like incoming orders that are barely increasing the index basically shows stagnation.

Figure 1

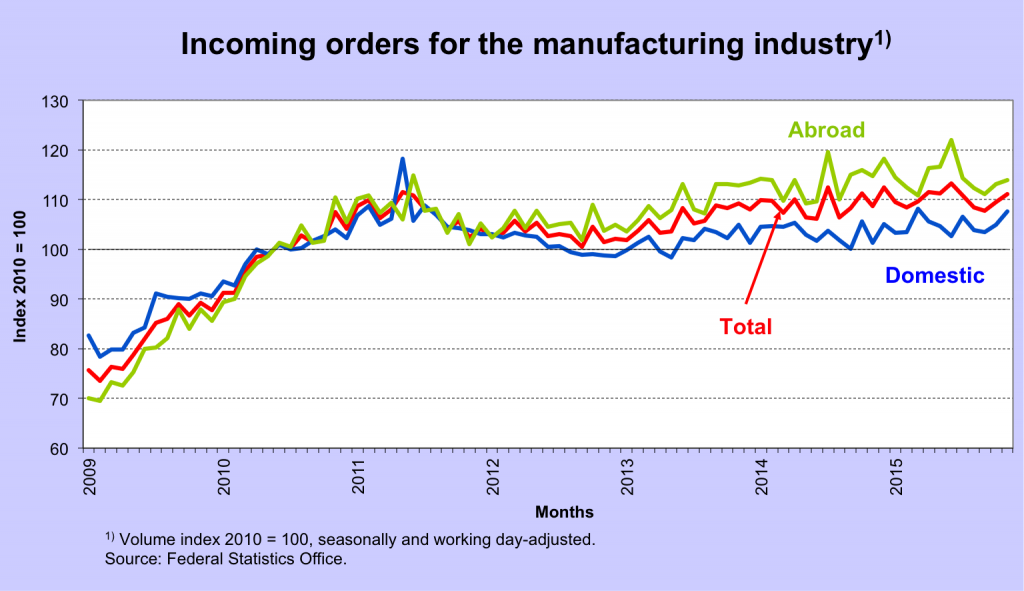

Dividing new orders between domestic and foreign ones shows that there are no appreciable impulses in either. While it is true that the slump in foreign orders did not continue in the third quarter of 2015, the slightly upward trend does not lead to anything more than stagnation (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

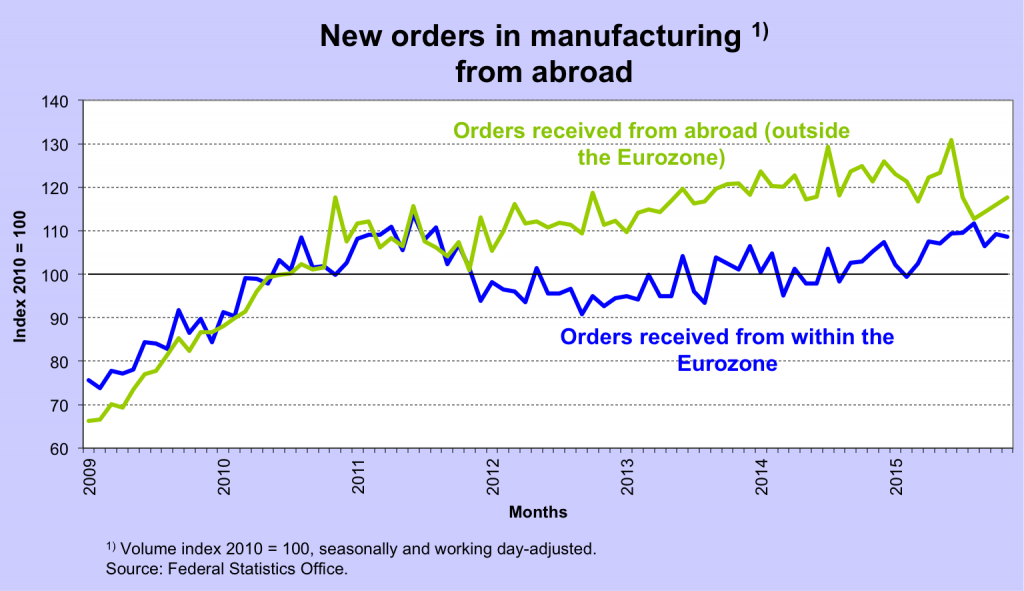

As Figure 3 proves, primarily non-European countries are responsible for the slump in orders. Orders from within the euro zone expanded.

Figure 3

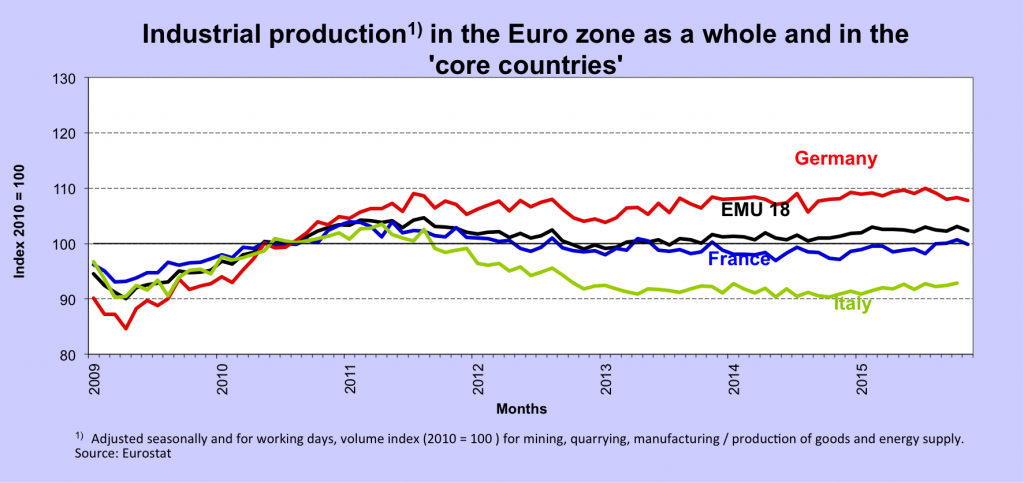

The most recent development in the euro zone as a whole gives nonetheless no reason for hope. Industrial output decreased once again. This is primarily due to France and Germany (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

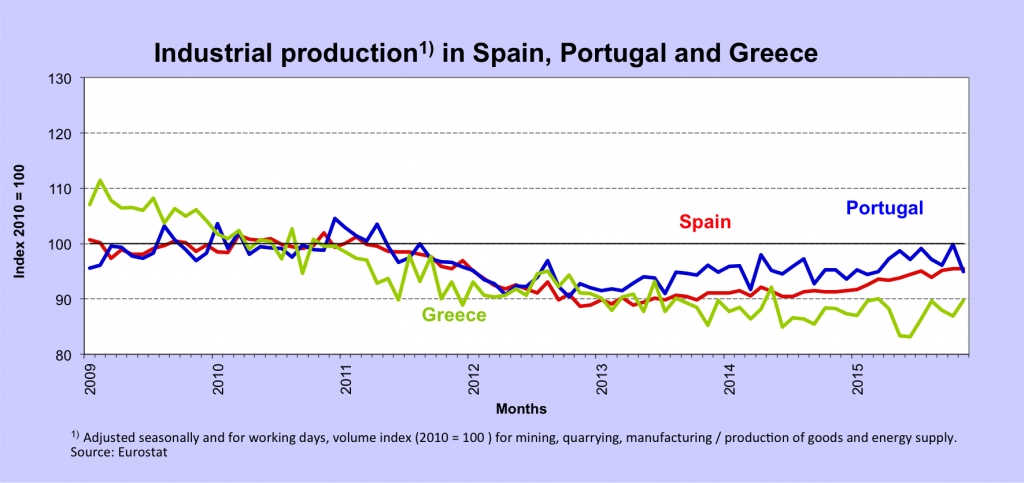

No progress was recorded in southern Europe in November either (see Figure 5). Portugal witnessed a slump in November and in Spain it became clear that the modest recovery in industrial output from mid 2014 will not last. The Greek situation is and will remain hopeless.

Figure 5

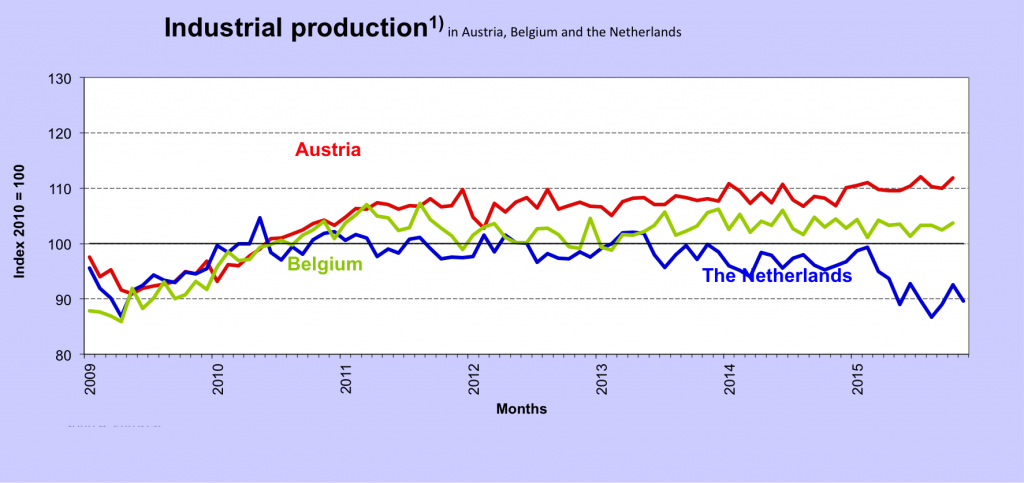

Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands show how difficult it is for the core northern countries to make progress. The Netherlands remain in a deep recession. Despite the multiple ‘reforms’ there is no sign of any economic revival in sight. The fact that the Dutch Minister for Finance Dijsselbloem believes that he can cure Europe with his recipes, even though he failed miserably at home, can only be described as tragic for Europe.

Figure 6

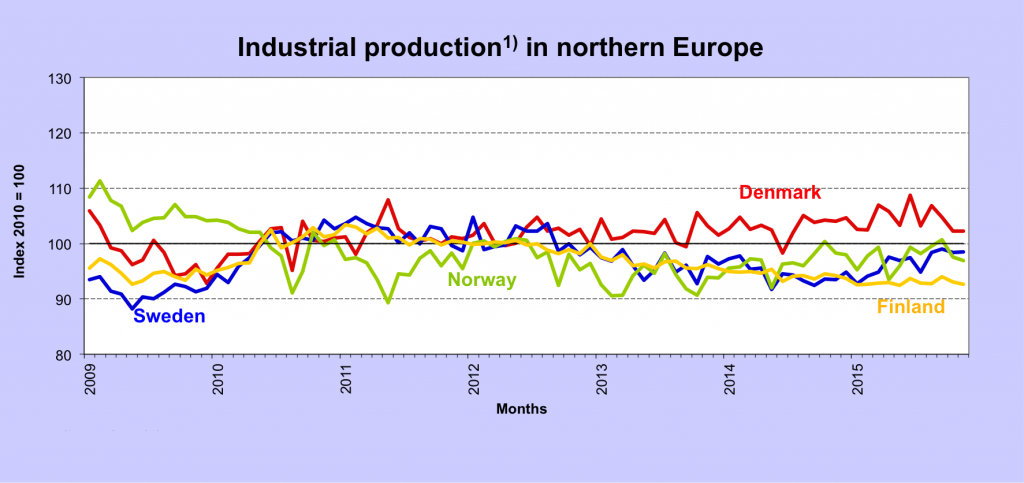

In northern Europe, the overall picture is virtually the same (see Figure 7). Denmark could not keep up its short-term momentum and falls behind again. Sweden is somewhat better off than a few months ago, but this is far from a real breakthrough. Interestingly enough, the Swedish Riksbank virtually obtained carte blanche to intervene in the currency market if weakening the Krona should turn out to be necessary. We will come back to this at the end of part two of this report. Even Finland, one of the countries with the most vocal ‘reform advocates’ within the Euro group, does not recover. On the contrary, it continues to slide downhill.

Figure 7

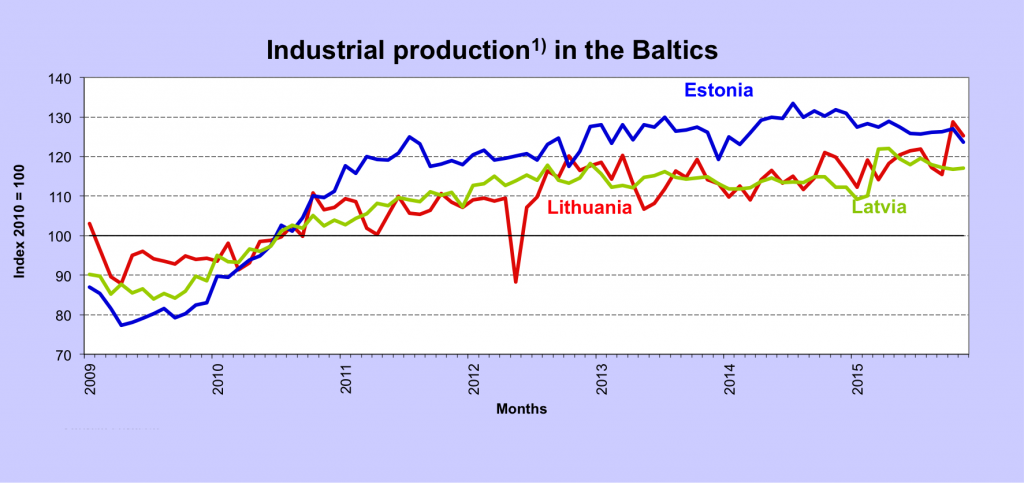

The Baltic States are also trapped in stagnation (see Figure 8). In particular, Estonia, which also belongs to group of the hard ‘reformers’ in Brussels, sees its economy going down the path towards what could very well become a recession. Lithuania and Latvia were both evolving in the right direction, but it seems that, at least in Latvia, this development reversed.

Figure 8

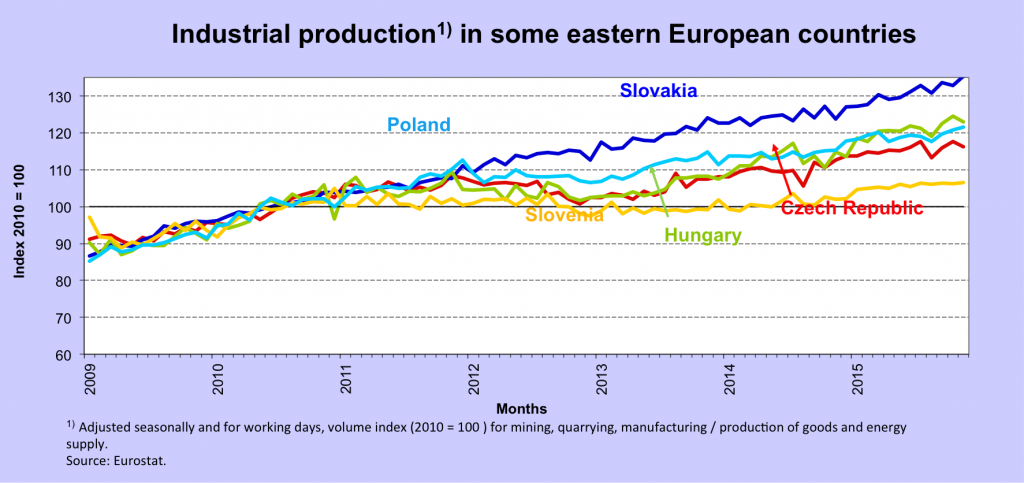

In the other Eastern European countries (see Figures 9 and 10) only Slovakia is on a steady upward path. Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland are progressing slightly upwards, but on a much slower pace than Slovakia. Slovenia stagnates again.

Figure 9

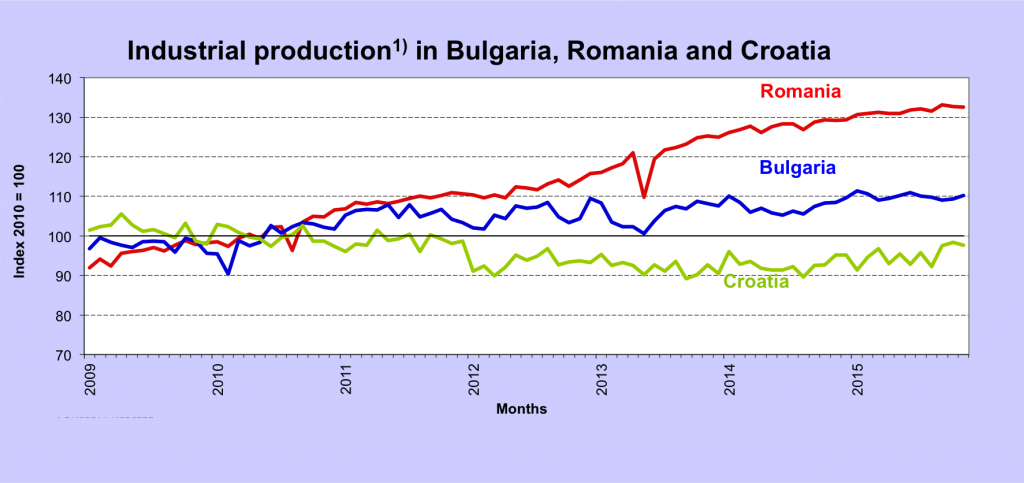

In Romania, the very weak movement upward is gradually transforming itself into stagnation. Industrial output is stagnating in both Bulgaria and Croatia.

Figure 10

I will explain in the second part of this article how the construction sector and the retail sector are evolving, how unemployment and prices develop and which economic policy proposals should be made and implemented to make the European economy work again.