The debate on European fiscal rules and specifically the German debt brake, which has been fueled by the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling of 15 November, is being conducted under legal, political and economic aspects. In our view, the latter must take center stage. Even if a budgetary decision complies with a law in a legally correct manner, this decision can be wrong in economic terms. This is because there is a risk that wrong decisions will lead to an even greater increase in debt because the economy suffers a massive slump.

The arguments of the advocates of fiscal rules

According to many financial experts, fiscal rules, including the German debt brake, are there to prevent governments from accumulating more and more public debt at the expense of future taxpayers to finance their spending desires. The sustainability of government debt is less guaranteed the higher the government debt ratio, i.e. the ratio of government debt to a country’s economic strength. If the (nominal) growth rate of an economy is lower than the (nominal) interest rate on government debt, tax revenues grow more slowly than the interest burden – when tax rates are unchanged. The proportion of government revenue that has to be used to finance the interest burden then increases and the fiscal room for manoeuvre decreases accordingly.

In order to remain capable of acting in terms of fiscal policy, taxes would then have to be increased at some point. In other words: according to this interpretation, additional government debt today harbors the risk of higher tax burdens tomorrow. However, higher tax burdens lead to inefficiencies and disincentives and settle like mildew over the private sector, whose innovative strength then diminishes. This dampens growth in the long term, making the constellation “interest rate higher than growth rate” even more likely or even cementing it. This dilemma should be avoided by setting limits to the spending behavior of governments through fiscal rules.

The warnings against high government debt ratios and the justifications for fiscal rules always follow these lines of argument. However, they suffer from the fact that they do not deal with the substantive interrelationships between macroeconomic growth rates, interest rate levels and government spending. The argument is based on mathematical conclusions “if” things occur in a certain way. Statements such as “If the interest rate is higher than the growth rate, then …” are made without clarifying the question of when and why such a constellation has occurred or can occur and how long it has lasted or can last. However, this is crucial for assessing how relevant the statement made is and which economic policy conclusions can be derived from it.

Growth rate and interest rate – interdependent variables

The three variables mentioned are closely interrelated. The growth rate of an economy is not externally determined in the short or long term, but is the result of the interplay between the economy and economic policy. Growth and productivity depend above all on investment behavior, on which the interest rate level in turn has a major influence. Conversely, an economy that is stagnating in real terms (i.e. price-adjusted) cannot have a positive real interest rate in the long term because investors, as the most important debtors, cannot generate a positive return on average when the economy is stagnating and therefore cannot generate a positive interest rate.

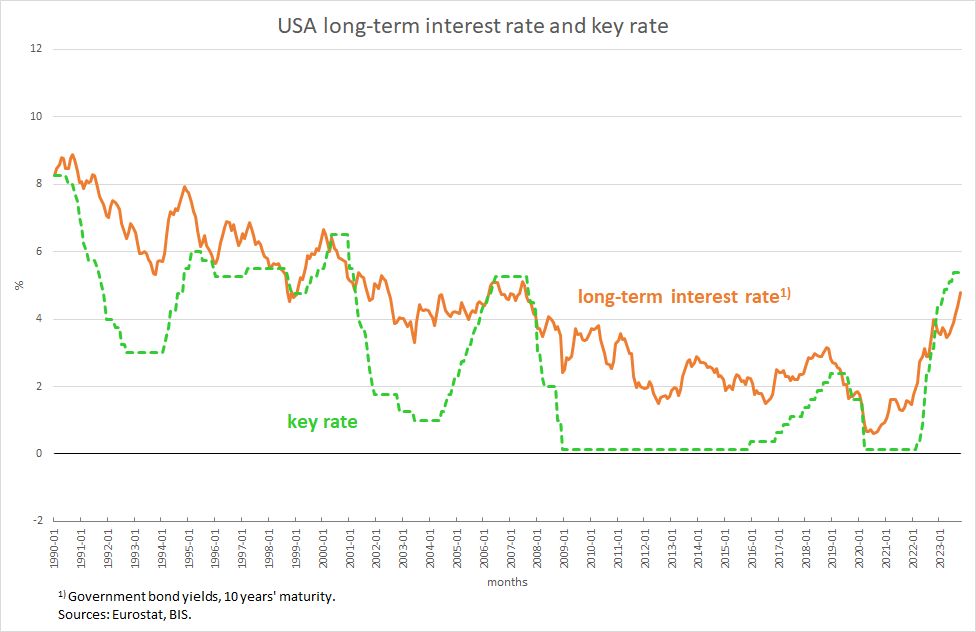

The level of short-term interest rates in all major industrialized countries (i.e. particularly in the EMU and the USA) is determined by the central bank’s key interest rates. As Figure 1 shows for the USA, long-term interest rates can never detach themselves from short-term interest rates because there are many substitution possible between financial assets with different maturities. Although there is massive speculation with government bonds, long-term interest rates remain on the course that the central bank determines with short-term interest rates.

Figure 1

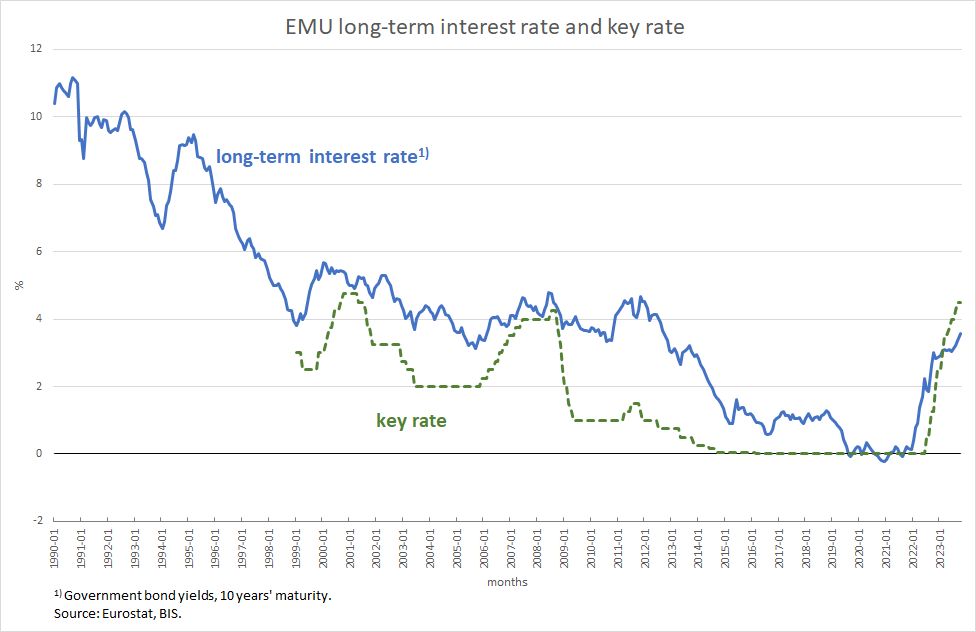

This is even more true for Europe (Figure 2) than for the USA. The small and very short-lived spike in the ECB’s key interest rates in 2011 shows that even such a small spike can have a major impact for several months due to speculation at the long end.

Figure 2

The dependence of long-term interest rates on policy interest rates means that constellations in which the growth rate is below the interest rate level are not unalterable natural phenomena or the result of the “judgement” of the financial markets, but the result of deliberate monetary policy decisions. They are never random and are generally not permanent. High government debt ratios could therefore cause difficulties for fiscal policy if, for example, as was the case in the 1970s and 1980s, monetary policy wants to put wage policy under preventive pressure with high interest rates.

Government debt – a long-term millstone around the neck of the private sector?

The neoliberal mainstream does concede that the state can and should automatically have an anti-cyclical and thus stabilizing effect on the economy through the tax and social security system, that a certain supply of public goods is necessary for the private sector to function properly and that the public capital stock can also be financed to a certain extent with loans for reasons of intergenerational fairness and to smooth the tax burden.

But even the financing of public investment with debt, the so-called golden rule of investment, is controversial. This is because – as Lars Feld, former chairman of the German Council of Economic Experts and current advisor to the Federal Minister of Finance, recently stated in a lecture in mid-October – “Debts that are incurred for investments [are] to be paid at some point and [also] represent a problem in the sustainability issue [of government debt]. There is no guarantee that government investments will lead to an economic return.” In addition, it is unclear which government spending should be regarded as investment. In this respect, the golden investment rule does not provide a clear criterion for limiting government debt. Consequently, the current German and European fiscal rules do not differentiate between consumptive and investment public spending.

Government debt as a counterbalance to private savings

These ideas miss the essential macroeconomic connection between government debt and the development of a country’s economic strength. This is because they primarily revolve around the question of whether and which public goods the state is allowed to finance with loans, but not whether the state has the permanent task of ensuring a macroeconomic dynamic that allows unemployment to be kept low and future tasks to be tackled proactively.

A market economy is by no means a stable system. The private household sector, for example, traditionally saves part of its disposable income. The overall reduction in demand, which is logically inevitable (as shown here), must be offset at all times by one or more of the three other economic sectors (companies, the state, foreign countries) to prevent a self-reinforcing economic downturn.

If the corporate sector does not fulfil the task of counteracting private households’ propensity to save through debt, or does not do so sufficiently, this task is concentrated on the state in large, largely closed economies such as the EMU and the USA. If the state’s hands are tied by fiscal rules that ignore this compelling macroeconomic context, there will be huge undesirable developments – regardless of whether monetary policy has set the interest rate correctly.

Debating the sense of fiscal rules without addressing these relations is therefore about as meaningful as arguing about whether you should make strawberry ice cream with or without sugar while the strawberries used burn in a pot on a hot hob. At its core, the discussion must revolve around the question of whether fiscal rules prevent the state from fulfilling its macroeconomic stabilization function in a timely manner and to the full extent.

A comparison between the USA and EMU

Empirically, the question of the appropriate level of government debt can be analysed on the basis of two large comparable regions, namely one that made every effort after the financial crisis of 2008/2009 not to allow government debt to rise in relation to gross domestic product (GDP) and one that had no rules in this respect and incurred debt on a grand scale. After all that we hear about the dangers of permanently rising government debt from financial scientists and regulatory politicians such as Lars Feld, the result can only be that the region with the rising debt has fared worse in every respect than the more solid region.

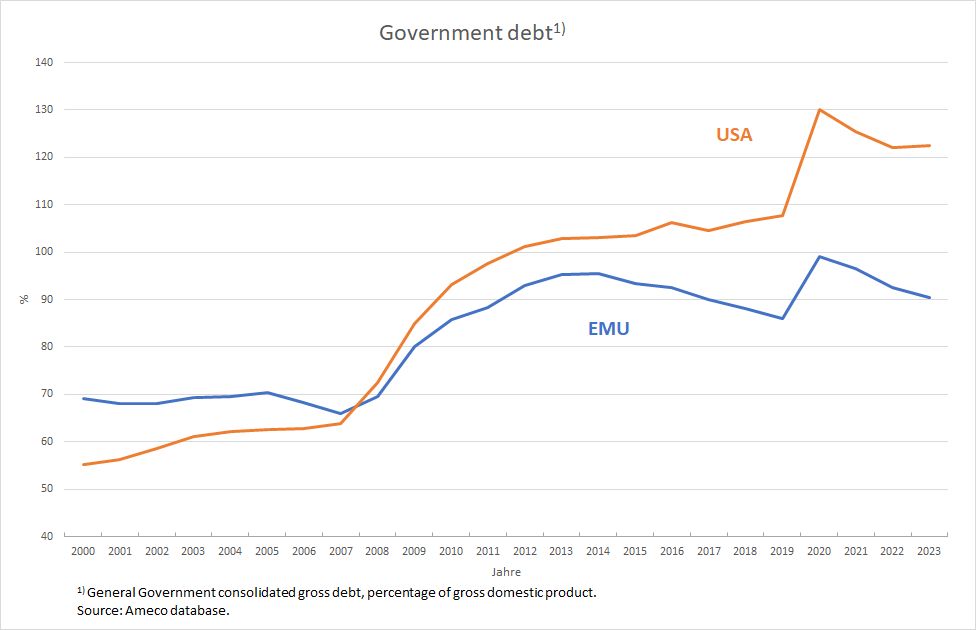

In the US, the ratio of government debt to GDP has risen virtually across the board over the past 22 years, apart from the brief decline in 2021 and 2022, which was a counter-reaction to the enormous increase during the coronavirus crisis (Figure 3). At over 120 per cent, the rate has now reached a level that never existed before the pandemic and which many consider to be very problematic.

In the EMU, on the other hand, following the sharp rise in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis and the subsequent euro crisis, the public debt ratio fell significantly from just under 70 per cent to 95 per cent between 2014 and 2019, by a good 10 percentage points to around 86 per cent. The pandemic-related surge to almost 100 per cent has also been largely offset in the meantime – the ratio now stands at 90 per cent, roughly the same level as in 2017.

Figure 3

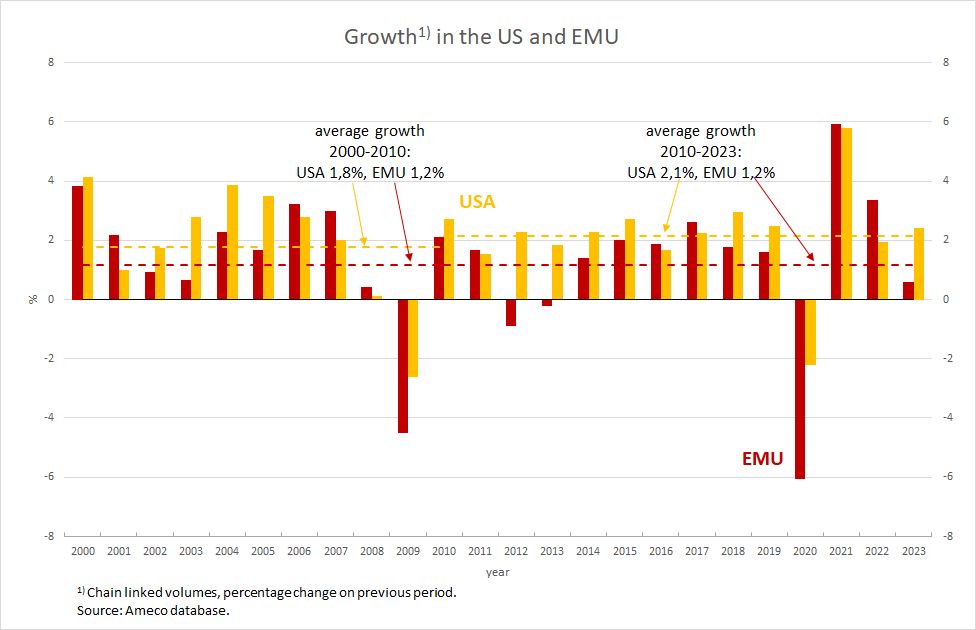

The result of this policy can be assessed on the basis of three macroeconomically relevant variables: growth, unemployment and inflation. In terms of growth (Figure 4), the USA was considerably more successful than the EMU: with average annual growth of 2.1 per cent in the period after the financial crisis to date, it performed better (EMU 1.2 per cent) and also achieved a higher figure than in the period before (1.8 per cent between 2000 and 2010). It is also striking that the USA lost significantly less economic income than the EMU countries during the two severe crises in 2009 and 2020.

Figure 4

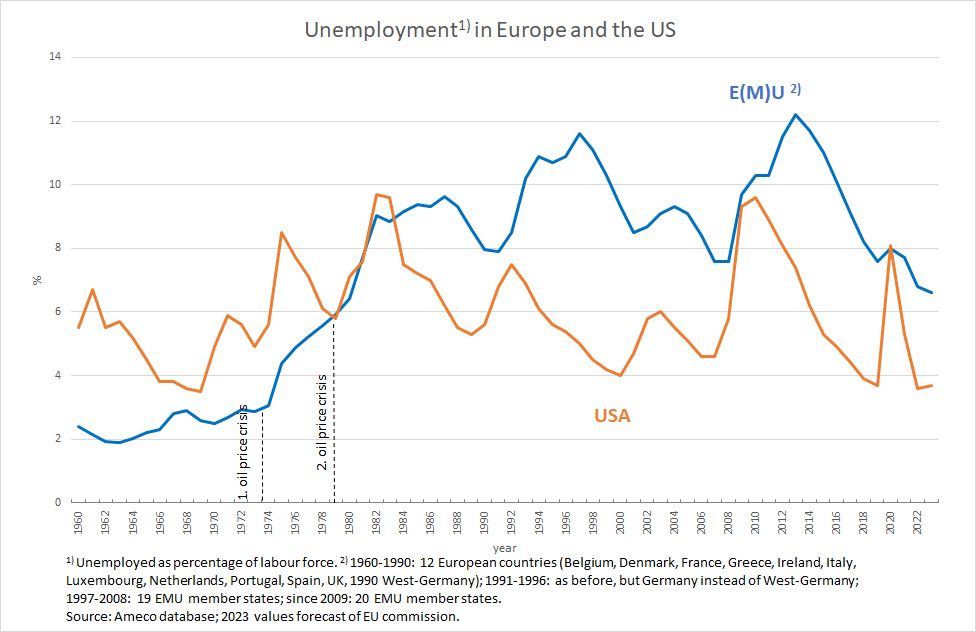

The US growth success was also reflected in the labor market (Figure 5). Although the US had the same unemployment rate as the EMU in 2010, the US managed to bring unemployment back to a full employment level much faster. Despite the decline in unemployment since 2013, the EMU is still a good 6 ½ per cent away from what could be described as full employment.

Figure 5

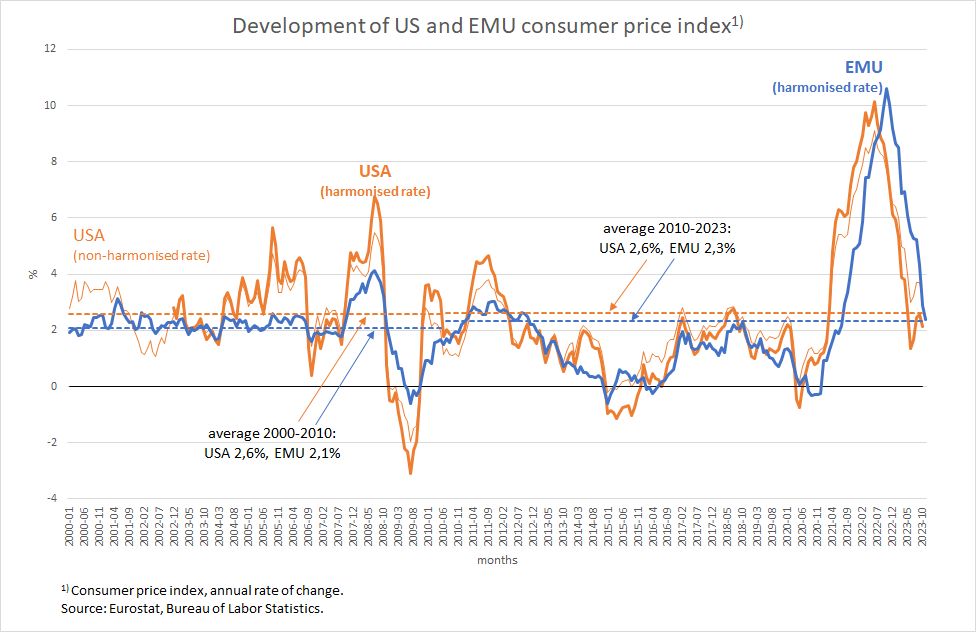

The US policy of government debt to stimulate the economy has also not had a negative impact on price trends (Figure 6). At an average of 0.3 percentage points between 2010 and 2023, the differences to the EMU are not worth mentioning. Moreover, such a difference – in contrast to the significantly larger differences in growth – is irrelevant. Ultimately, it does not matter which rate of price increase is agreed upon and to which all players adjust in the long term. The only important thing is what the real economic outcome is in the end.

Figure 6

The US government dares to counterbalance the private propensity to save

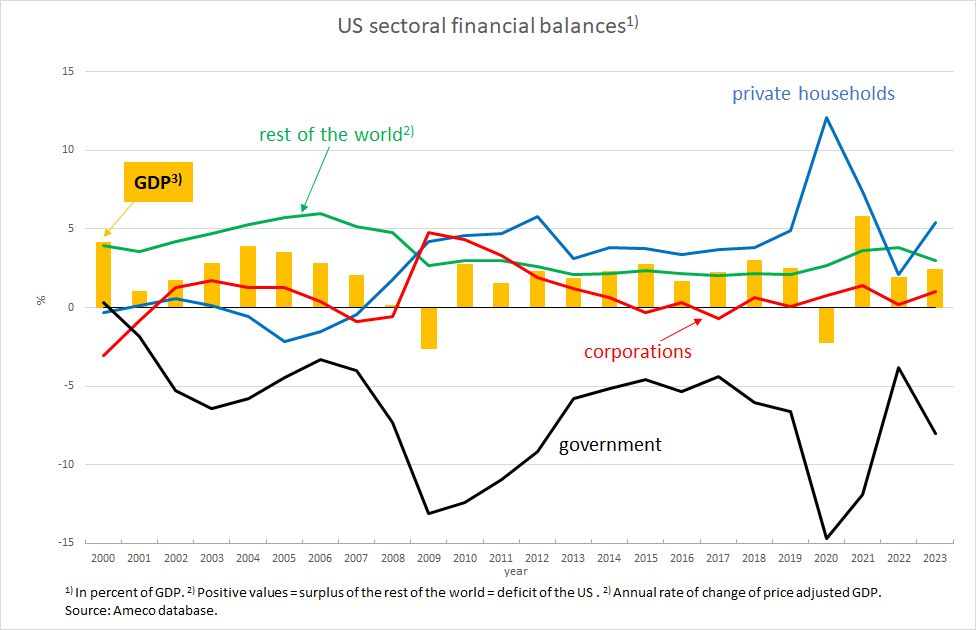

Instead of arguing about individual budget items, the question that should now be highlighted is: Why has the USA, despite all the prophecies of doom from financial experts, managed to achieve far better economic development with much more government debt than Europe has managed with its fiscal rules? Although this question can never be fully answered, the answer can be approximated to a certain extent by looking at the development of the financial balances of the four economic sectors. Without these balances, as explained above, it will never be possible to understand the significance of the government deficit and its development.

Figure 7 shows that the USA is faced with a constellation in which the state has no choice but to take out new loans every year. All other sectors, including companies, have almost always been above zero for two decades, i.e. in savings mode: they are recording revenue surpluses. As planned revenue surpluses can only be realized in the economy if another sector accepts deficits and thus prevents overall economic income from falling, the state has done what it had to do to prevent the economy from shrinking.

Figure 7

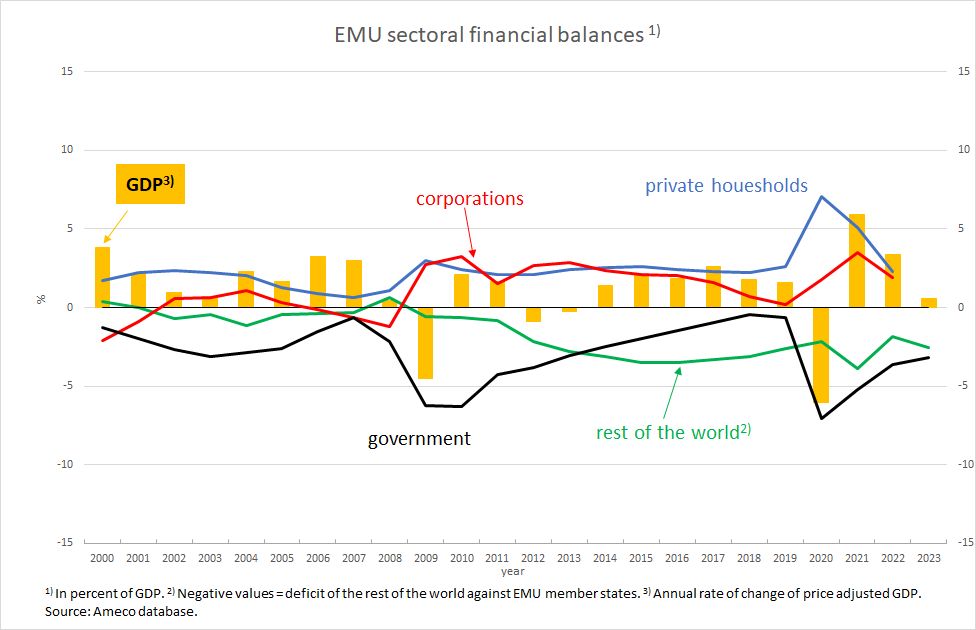

In Europe (Figure 8), the overall constellation is not dissimilar as far as the private household and corporate sectors are concerned. Here too, the private revenue surpluses since 2010 have not allowed the state to stop incurring new debt in any year. However, in contrast to the USA, the EMU has a current account surplus – the curve for foreign countries is below zero: the rest of the world is indebted to the EMU, i.e. transfers demand to it. In the USA, it is exactly the other way round: the rest of the world is running surpluses there and thus withdrawing demand from the USA. It is solely thanks to the surplus demand from the rest of the world vis-à-vis the EMU that new government debt in Europe was able to fall continuously between 2010 and 2019 without the region sinking into a permanent recession. Incidentally, the German surplus was the main contributor to the European current account surplus. At the same time, Germany’s consolidation strategy was the main factor behind the reduction in new European debt.

Figure 8

Economic policy conclusions

The analysis of the financial balances for both economic areas suggests that the USA has avoided considerable losses in growth, especially in times of crisis, with a faster and quantitatively much more significant counter-reaction by the state. In the course of economic dynamics, it is not only important that the state shows deficits in the ex-post analysis of balances, but also that the state acts quickly and decisively in the event of a restrictive movement by private individuals in order to prevent a slide into a deep crisis. Only if the state is able to act at all times can it intervene in good time. However, this is precisely what legal regulations such as the German debt brake or the European debt rules prevent, because they simply do not recognize prevention.

But even in times without a crisis, it is important that the state aligns itself with economic development and not with abstract rules. Rules that only focus on emergencies, but not on the fact that the state always has the task of counterbalancing private savings plans in the current constellation of balances, are misguided from the outset. Because almost all countries in Europe endeavored not to further increase or even reduce government debt after the financial crisis, they accepted the fact that economic development showed little dynamism and thus failed to reduce unemployment to full employment levels. The fact that there was any upward momentum at all is thanks to the surpluses with non-European countries, which demonstrates the dependence of European development on the economic situation in the rest of the world – a dependence that is rightly criticized by many.

In other words: If states do not succeed, even with zero interest rates as in the 2010s, in getting companies to systematically and predictably, i.e. actively, take the debtor position, the state will have to fill the demand gap with permanently and permanently increasing debt. A comprehensive analysis of this kind is the basic prerequisite for arriving at any meaningful economic policy statements. Anyone who looks at the state in isolation or mechanistically limits themselves to interest-growth ratios is not contributing to the solution of economic policy problems but fueling them.