In our Atlas der Weltwirtschaft 2022/2023 we included a special section dealing with the countries in Eastern Europe that are members of the EU and in some cases even members of EMU. Some of these countries have recorded enormous losses in international competitiveness over the past two decades, as can be seen from the real effective exchange rate of their currencies. A scenario of this kind is now looming again.

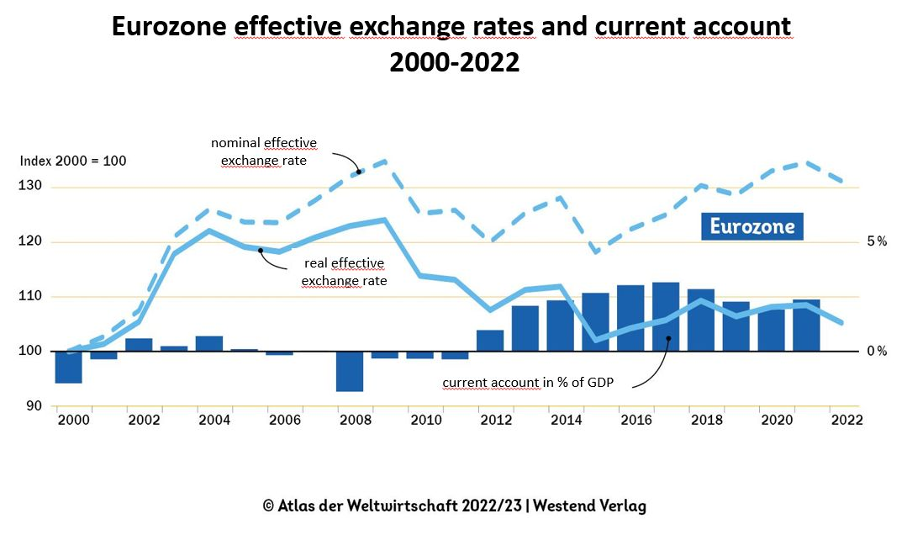

Between 2000 and 2022, Bulgaria, for example, experienced two massive surges in its real exchange rate against the euro area. This can be seen in figures 1 and 2 (both reproduced from the Atlas): The real effective exchange rate of the euro (the solid line in figure 1) rose by 20 percent between 2000 and 2004, remained roughly constant until 2009, then fell again, and has been roughly 10 percent above its 2000 starting value for the last five years. This means that the competitiveness of the euro area deteriorated until the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008/2009, but then improved again. In response, the balance of the euro area current account increased significantly (the blue bars in the chart are in positive territory with values of 2 ½ percent).

Figure 1

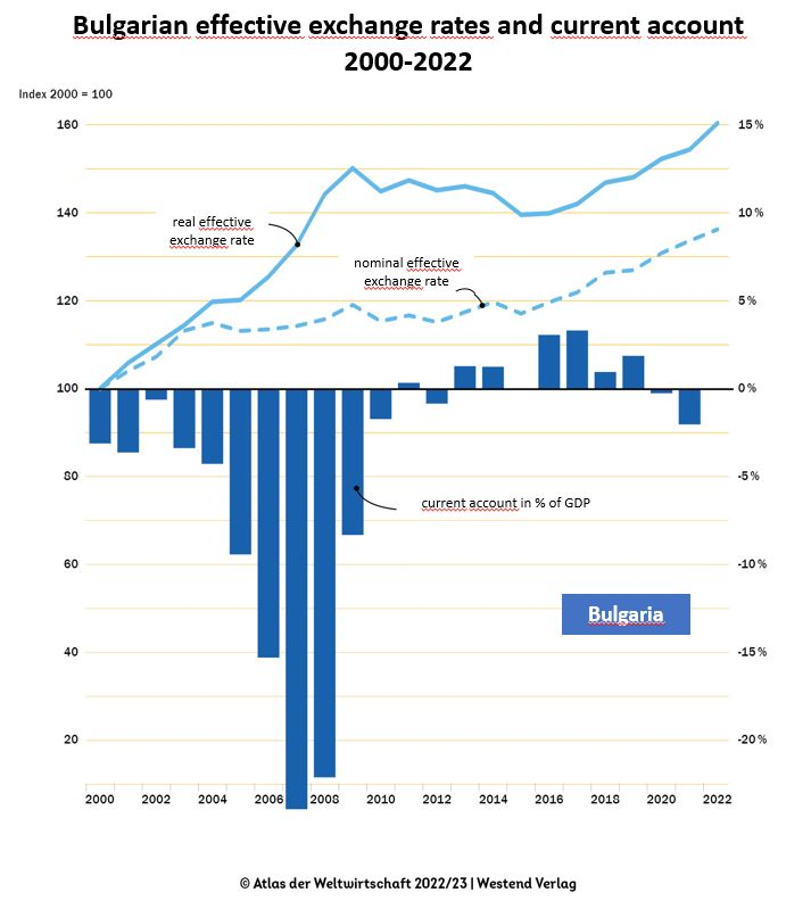

Bulgaria’s real effective exchange rate, on the other hand (see Figure 2), increased by about one-fifth relative to the euro area after pegging its currency to the euro in 2005 until the 2009 financial crisis, then declined somewhat and increased sharply again from 2017. In 2022, it was about 50 percent higher than that of the Eurozone. The fact that the current account balance did not slip into negative territory again as sharply as in the first decade is due to western firms producing locally with highly productive technology for Bulgarian exports. In the short term, therefore, the current account is no longer such a clear macroeconomic indicator of undesirable developments as it was in the noughties.

Figure 2

Something similar has also taken place in emerging economies in Northeastern Europe, such as Estonia and Lithuania. These two countries fixed the exchange rate of their currencies against the euro as early as 2004, well before they joined EMU in 2014 and 2015, and subsequently had much higher growth rates in unit labour costs (ULC) than the EMU average. This led to a major crisis in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, which was only overcome with wage cuts and a resulting domestic market weakness. As shown in the atlas, only a massive migration of workers mitigated the consequences for the labour market.

The wage problem in emerging countries remains unresolved

Massive losses of international competitiveness cannot be sustained by companies in any economy in the world. As explained in the Atlas, only western companies that bring their highly productive technology to these emerging countries and produce there can survive such a deterioration in the cost situation for any length of time. This is because, thanks to their high productivity, they have far lower ULC from the outset than their competitors in the high-wage countries. If the gap in ULC, and thus the cost advantage, is immense at the beginning, it only gradually melts away, even if wages rise excessively in the low-wage country selected by western producers.

Domestic firms in the low-wage countries, on the other hand, whose productivity at the outset was much lower than that of their western competitors, stand little chance in the event of excessive wage cost increases. They cannot adjust their productivity to that of western competitors as quickly: Initially, they had less experience in the leading technology, hardly developed international sales structures, and poorer financing conditions for investments. Even if these factors have gradually improved, this is of no help to the companies that have had to exit the market in the meantime.

And so the population – with the exception of those who are employed by the western companies – view the dominance of western companies in their own countries with increasing skepticism. Moreover, the loss of competitiveness means a loss of jobs. As a result, more and more workers are leaving their home countries if they do not see any future prospects for themselves there, even after many years.

In the wake of the recent energy and food price crisis this problem seems to live on: Indeed, price developments over the past year and a half have been reflected more strongly in wages in the Eastern European countries than in Western European countries – the first group faces wage-price-spirals, the latter not. This can be concluded from a comparison of the development of overall ULC. That puts once again massive pressure on domestic companies in the eastern countries.

If the countries are part of the European Monetary Union (EMU) or have pegged the exchange rate of their currency to the euro, the cost problem for their companies is obvious: A stronger rise in ULC compared to the main trading partners will lead a loss of international competitiveness. If the countries still have independent, flexible currencies, nominal devaluations can cushion cost increases in national currency and thus protect competitiveness. But concerns about strong reactions on the foreign exchange markets, i.e. a devaluation that significantly exceeds inflation differentials and thus makes all imports excessively expensive, force central banks to raise interest rates beyond those of the European Central Bank (ECB). This weighs even more heavily on investment activity in the countries concerned than in the euro zone.

Loss of international competitiveness under the euro

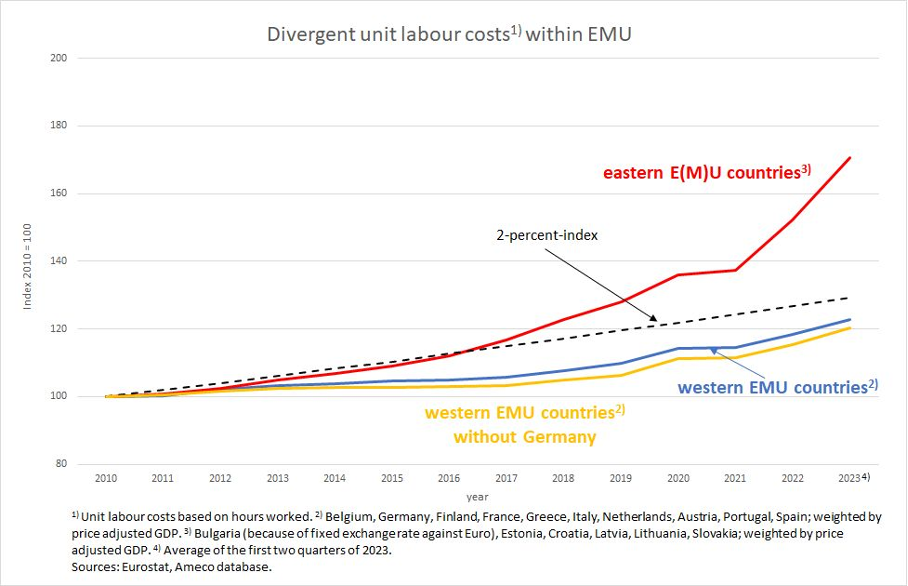

To illustrate the increasing tensions, we have summarized the relevant data for some Eastern European countries that are part of EMU or have a fixed exchange rate against the euro (Bulgaria) and contrasted it with the trend in 10 western European EMU countries from 2010 onward (Figure 3). The result is frightening. While ULC growth (per hour) in the western countries actually remains below the level that would be compatible with an inflation target of 2 percent (corresponding to the dashed line), the Eastern European labour costs are growing much too strong.

Over the past five years in particular, wages in the Baltics, but also in Slovakia, Croatia and Bulgaria, have grown far too fast compared with the development of domestic productivity and compared to the West. In the current year, for which corresponding figures are available for the first half of the year, the gap with western Europe is likely to widen once again.

Figure 3

The graph also illustrates that the western EMU countries excluding Germany (yellow line) are below the overall development of the western countries including Germany (blue line) in the period shown. The reason for this is that countries such as France and Italy have endeavored to make up for the German lead in ULC from the noughties through their own wage restraint.

Loss of international competitiveness under an independent currency

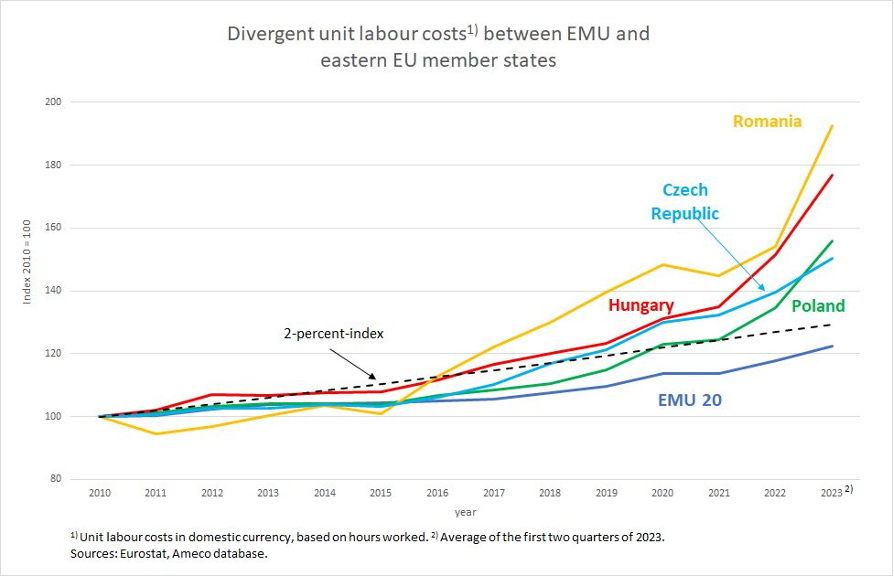

What about the most important Eastern European EU countries with independent, flexible currencies? Calculated in domestic currency, ULC in these countries have also grown much stronger compared with the euro zone (Figure 4).

Figure 4

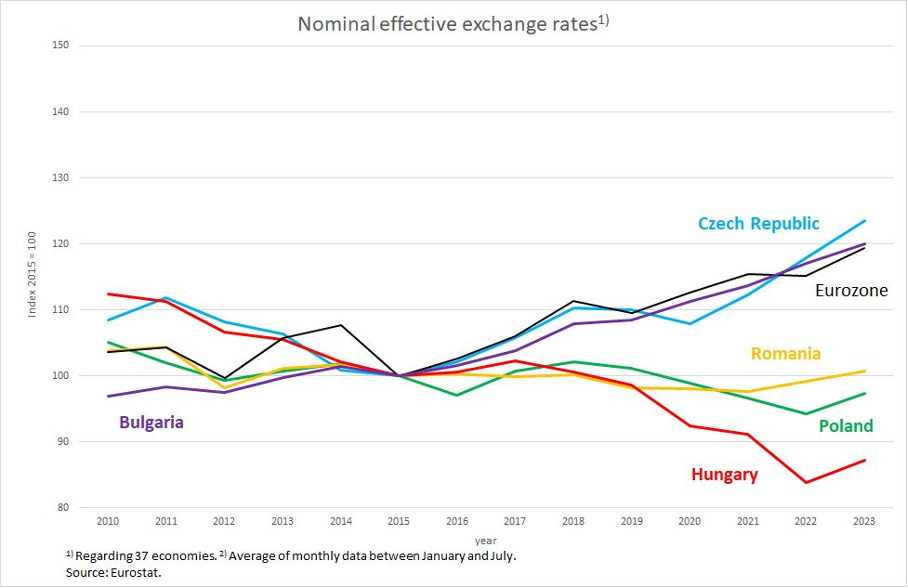

But these countries were able to avoid such massive losses in competitiveness as in Bulgaria or the Baltic states in the past decade thanks to devaluation. Hungary in particular, but also Poland, took advantage of the exchange rate valve: Their nominal effective exchange rate fell or stagnated, while that of the euro rose (figure 5). Only the Czech crown appreciated again significantly in nominal terms in parallel with the euro after 2015.

Figure 5

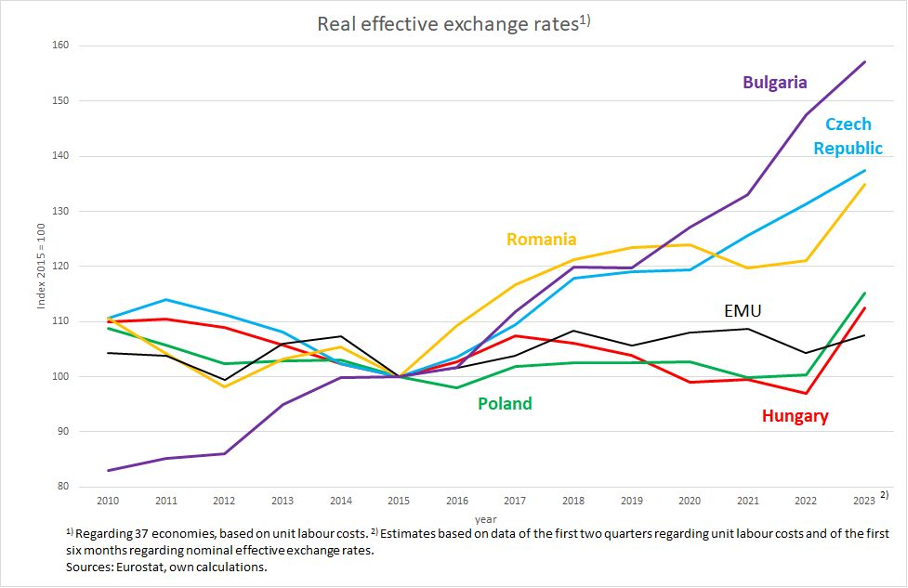

The result of these adjustments is shown in figure 6. The real effective exchange rate on a ULC basis, which simultaneously reflects internal ULC developments and external exchange rate developments, is the most comprehensive measure of changes in competitiveness at the level of a country. In the Czech Republic, for example, this real exchange rate has appreciated strongly since 2015, taking a heavy toll on the country’s international competitiveness. Romania also depreciated too little in nominal terms to maintain its real effective exchange rate at the 2010 starting level: Instead, it is now around 30 percentage points above that of the euro area.

Figure 6

Bulgaria’s distress, already described above, is also evident in figure 6: The situation there is even worse than in the Czech Republic. This shows that unilateral exchange rate pegging can cause major problems. It offers no protection against the loss of international competitiveness if it is not accompanied by a wage policy that takes account of average domestic productivity advances and is oriented toward the inflation target of trading partners.

By contrast, Poland and Hungary have successfully defended their competitiveness vis-à-vis EMU through a combination of rather moderate ULC increases and nominal depreciation of their currencies until 2022. At the current margin, however, the problem also appears with these two countries that the high price increases of the last two years regarding energy and food have found their way into wage settlements to a greater extent than on average in the euro zone.

The ECB’s interest rate yoke has effects far beyond the Eurozone

Since small countries’ currencies are repeatedly the object of speculation in the foreign exchange markets, an adequate, i.e. timely and quantitatively appropriate, reaction of nominal exchange rates to differences in price or ULC developments between trading partners is by no means guaranteed. The smaller countries traditionally address this problem by hedging their currencies through interest rate policy: Relatively high interest rates compared with more inflation-stable foreign countries – in this case the euro zone – are intended to maintain the attractiveness of their own currency. In addition, they hope to get inflation under control in this way.

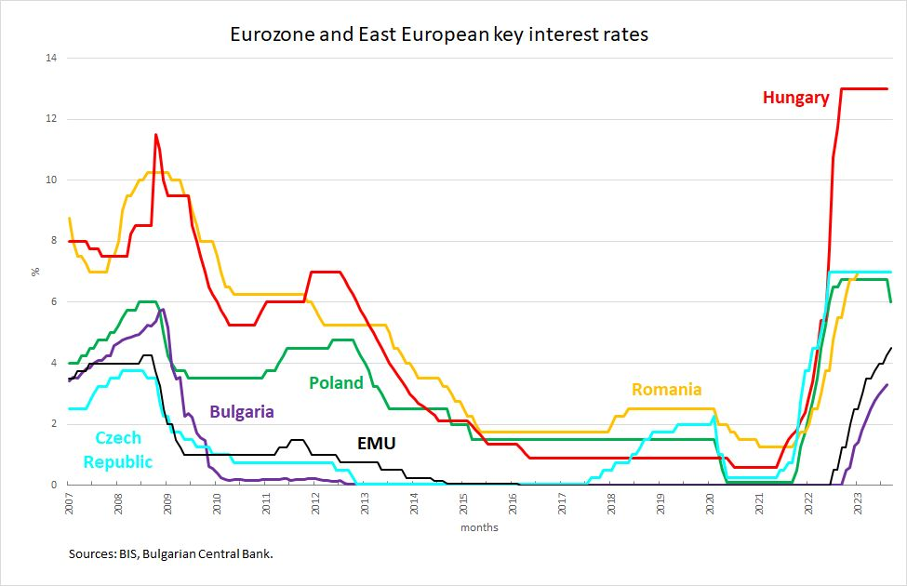

Figure 7

And so the central banks of the Eastern European EU countries with independent currencies began to raise interest rates massively as early as the summer of 2021, well before the ECB in turn began tightening monetary conditions, as can be seen in Figure 7. The Hungarian central bank took a particularly radical approach, as consumer price inflation rates shot up earlier and much more massively than in the euro area and the nominal effective exchange rate depreciated by eight percent between May and September 2022: It raised the key interest rate from 5.4 to 13 percent within those four months. The nominal exchange rate then rose again almost to the level it had had in the previous two years.

In Poland, too, the massive increase in key interest rates from 0.5 to 6.75 percent within a year had a stabilizing effect on the nominal exchange rate after some time. Here, as in Romania and the Czech Republic, consumer prices had not increased to the same extreme as in Hungary, and accordingly the key interest rate hike was only half as sharp as in Hungary.

However, the effect of monetary policy on price developments is rather small in all the countries considered here: Consumer price increases are still above the EMU average – and in some cases significantly so. They obviously reflect the pressure exerted by ULC. In this respect, it is hurting domestic companies that currencies are not depreciating accordingly. The high key interest rates seem to have less influence on wage agreements than to fuel the danger of carry trades: The latter arises because speculators increasingly demand these currencies in order to earn from the interest rate differential against the euro. As a result, these currencies depreciate less in nominal terms than is actually necessary or even appreciate in the short term, which again worsens the competitive position of domestic companies. In the Czech Republic, for example, such a process of nominal appreciation already seems to be taking place.

The dilemma between fighting inflation and the danger of carry trades, in which the Eastern European central banks find themselves, is exacerbated by the interest rate policy of the ECB. The ECB’s response to the corona and energy crisis-induced price surges started in July 2022 with sharp interest rate hikes, although the much feared wage-price spirals failed to materialize on average in the euro zone. In doing so, it has set an interest rate level against which Eastern European central banks feel they have to compete.

In Frankfurt, no one has thought of giving the Eastern European neighbors a helping hand by promising to hedge the necessary nominal devaluations of the currencies against excessive reactions on the foreign exchange markets. And in Brussels, as in the past two decades, there is still no concern about the monetary constellation in the east of the EU.

Conclusion

Companies located in Eastern Europe are facing three obstacles: first, high cost pressure due to wages, second, high interest rates and thus poorer financing conditions, making it more difficult to increase productivity through real capital formation, and third, foreign competitors that are constantly gaining competitiveness. To be successful, one must have stable real exchange rates on the one hand and low interest rates on the other. Hardly any country in Eastern Europe has achieved this combination.

The solution to this problem lies in wage and income policy, which the state cannot leave to the collective bargaining partners alone. Only the state can develop guidelines that make monetary stability in the above sense possible if it also ensures social compensation for the weakest members of society. Wage policy as a whole must be balanced in such a way that domestic jobs are not jeopardized.

Yet wages and their central importance for the stability of a country’s economic development still seem to be something of a taboo subject three decades after the fall of the Iron Curtain. And this is the case, although the economic stability and prosperity of the eastern neighbors is in the highest interest of the Western European states – especially in a geopolitically tense situation like the present one, in which the cohesion of the EU is invoked almost daily by almost all high-ranking politicians. The ECB, too, cannot be interested in a euro crisis in the Baltic states, for example, nor in currency crises on its own doorstep. Are those who bear responsibility in Europe simply unwilling or unable to look beyond their own horizons and to cut off old ideological braids such as “wages are exclusively a matter for the markets or, at best, the collective bargaining parties,” “the central bank is exclusively committed to price stability in its currency area,” or “monetary policy does not cooperate with anyone; at best, it only gives advice to others”?

In the end, citizens across Europe are paying the price for such a continued blinkered mentality on the part of our responsible politicians and the economists advising them.