Based on what it calls a data-based approach, the ECB raised interest rates once again on May 4, 2023. This time it is “only” 0.25 percentage points, but the ECB emphasizes in its statement that there are “ongoing high inflation pressures” that compel it to act this way. On the same day, Eurostat published the values for the change in industrial producer prices in the domestic market. In March 2023, producer prices were still 5.6 percent higher than their value a year earlier, but for the second time they have fallen compared to the respective previous month’s value.

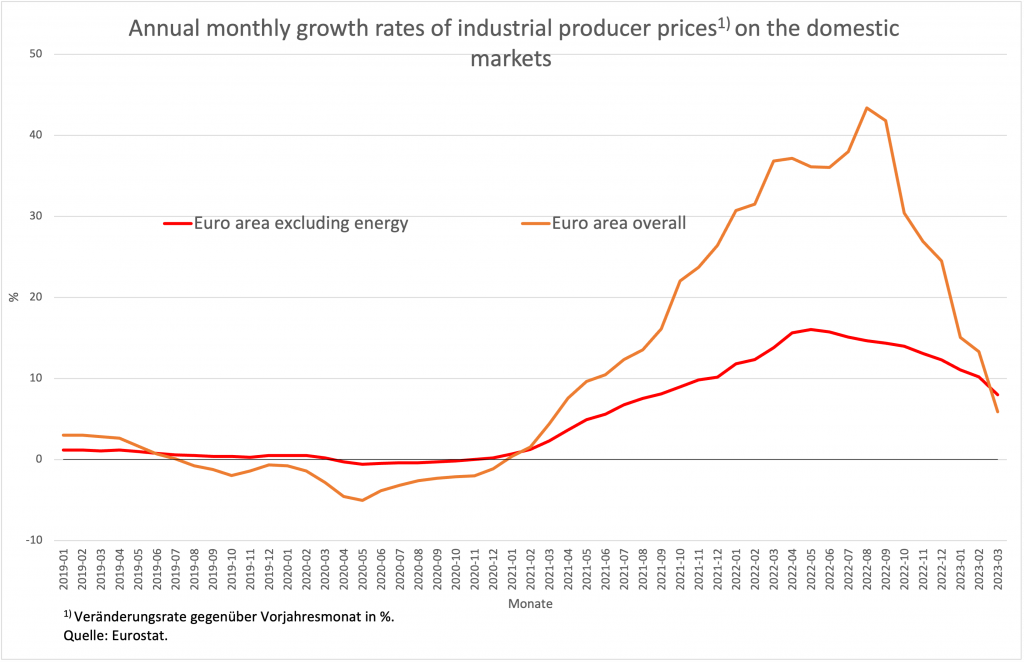

One wonders what persistent high inflationary pressures should be when prices at the most important upstream level are falling in absolute terms. If we look at European producer prices in the usual way of calculating them, namely as a rate of change compared with the same month of the previous year, it is immediately clear that there is no longer any question of sustained inflationary pressure (Fig. 1). On the contrary, much faster than inflationary pressure was built up (even before the start of the war in Ukraine at the end of February 2022, a growth rate of 30 percent had been reached for European producer prices), it is being reduced again.

Figure 1

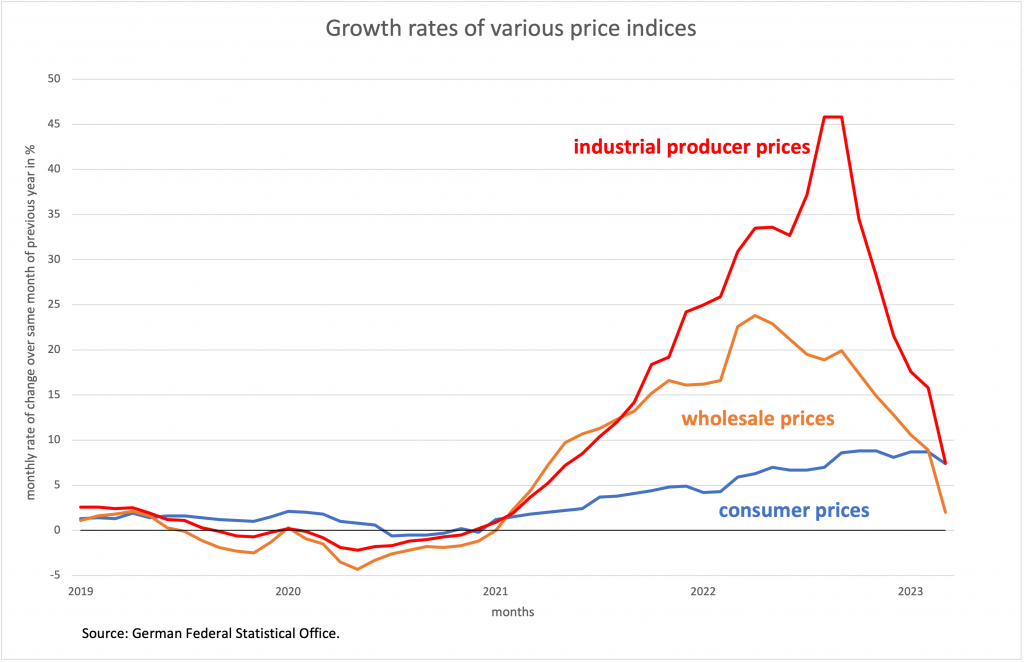

The same is true for Germany (Figure 2). Wholesale prices are also plotted here, which also clearly point to a sharp slowdown in inflation momentum.

Figure 2

It is worth recalling what the prevailing neoliberal doctrine said last year about the importance of producer prices. Hans-Werner Sinn noted last September that in August 2022, “commercial producer prices, which measure what happens at the preliminary stages of industrial production, were a whopping 46% higher than in the same month a year earlier, following a 37% gain in July.” If, Sinn continued, one “consults the long-term correlation between the rates of price increases in industrial producer prices and consumer goods, the 46% for Germany (in August) would imply consumer goods inflation of up to 14% for November (2022) in the pipeline”.

As we know, things have turned out differently and one wonders what Mr. Sinn has to say about the fact that growth at the producer level has now fallen to almost five percent and that even if prices do not fall further, a negative year-on-year rate will be reached in a few months? Does he then also predict that this will be felt at the consumer level with some delay?

I doubt it. And the reason is obvious. After all, Hans-Werner Sinn also said last September that the ECB

“…must accept the reproach that it has contributed significantly to the current inflation… because since the Lehman crisis it (has) allowed the central bank money supply to increase twice as fast as the FED in relation to economic output and (has) generated a great deal of Keynesian debt steam by buying the government securities of the euro countries on a huge scale, namely for 4.4 trillion euros. Through the purchases, which since the summer of the Lehman year (2008) comprised 83% of the money supply growth in relation to economic output, it has pushed interest rates on government securities down to the neighborhood of zero. In doing so, it has caused the states to take on more and more debt in an almost breakneck manner, disregarding all debt pacts. These measures will push the general government debt ratio, including EU debt, well above 100% in the long term. Since government debt increases aggregate demand, this has had clear effects on inflation. The Corona-related supply shortages and energy shortages were the spark of inflation, but the sovereign debt was the tinder that now keeps the fire burning.”

The national debts still exist, but the inflation fire resulting from it according to the opinion of the ruling doctrine, that no longer exists. But because the thesis of monetary overexpansion advocated by Sinn and many others is also secretly believed by many in the ECB (the German, Dutch and Austrian regional bank presidents are likely to be the typical advocates), the ECB can no longer find its way back to a calm and reasonable diagnosis.

Real inflation always has to do with the fact that a one-time price increase develops into a process in which new inflationary impulses are given again and again, which quickly work their way through the entire economy. There can never be such a “breather” in an inflationary process as has now been observed for several months. The tremendous pace of decline in growth rates would be absolutely impossible at any stage of the economy if an inflationary threat had arisen after the initial impulse. The ECB’s “ongoing inflationary pressure” is a misinterpretation that shows that people at the top of the ECB are working with false ideas about the dynamic development of an economy.

However, the ECB should at least be able to recognize that, on a European scale at any rate, the development that the ECB leadership has repeatedly cited as a danger, namely a price-wage-price spiral, has not occurred. Producer prices would not have been falling in absolute terms for months if the trade unions had succeeded on a broad front in keeping their members free from the burden of price increases that are in their origin externally induced.

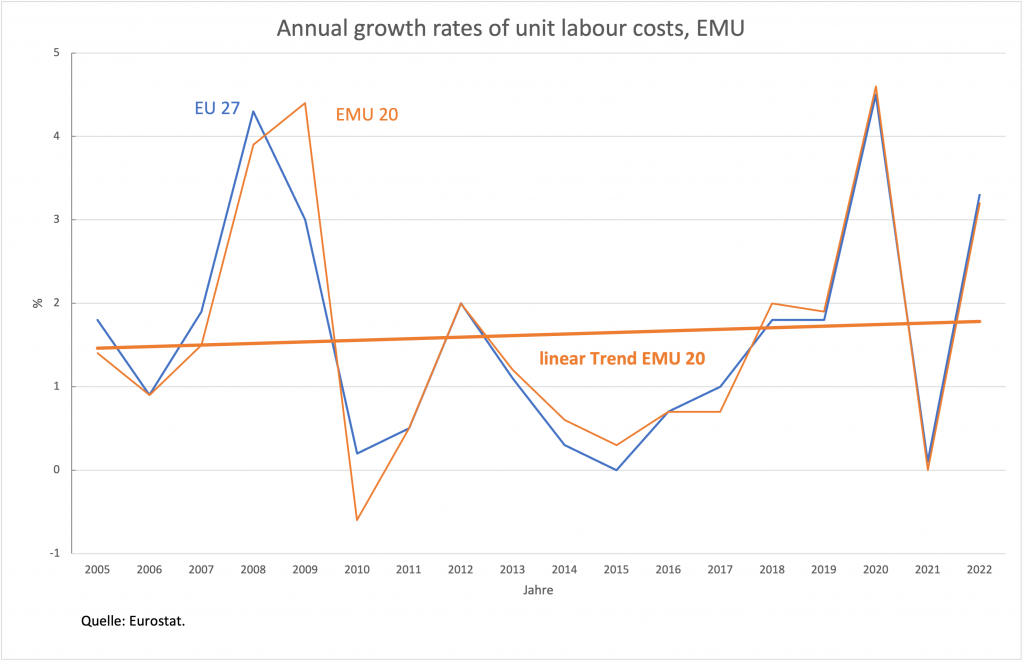

As shown many times, the decisive determinant of longer-term inflation is the development of unit labor costs. In the EMU, they have not risen for many years to the extent that is appropriate for a two percent inflation target, and even in 2022 their development is not inflationary at just over three percent (figure 3).

Figure 3

In the largest member country, Germany, there were still large real wage losses last year. Nevertheless, most of this year’s deals do not suggest that the dreaded spiral has begun. One-off payments have been used to prevent real wages from falling again. Statistically speaking (i.e., based on the average basket of goods), lower wage groups will even see increases in real wages. Beyond this year, however, the agreements are not inflationary, but are within the bounds of what is compatible with an inflation target of two percent in the medium term.

Even if, as seems to be the case in Germany, the normalization of price developments is less clear at the consumer level, that is no reason for monetary policy to remain on the brakes. If, in certain areas such as retailing, competition is not great enough to force companies to pass on price cuts quickly at the upstream stage, it is the Cartel Office that has to intervene but not the central bank. When the so-called transmission channel that monetary policy relies on is clogged by a lack of competition in the retail sector, interest rate hikes do damage without fixing the problem.

At the same time, the economy in the largest member state is literally collapsing, as the latest industrial orders show, and economic policymakers are standing idly by. But more on that next week.