It is truly paradoxical: in the USA, where the state has successfully been relied on for decades to keep the economy running, Donald Trump’s billionaire advisors are now calling for a radical reduction in the state’s influence. Libertarians like Elon Musk and Peter Thiel, like their Argentinian role model Javier Milei, firmly believe that only by radically reducing the influence of the state can the market economy be revived and revitalised.

Whether Trump really buys this radical cure is an open question. Given the experience of his first four years in office, he probably realises how heavily the US depends on state stimuli via government debt. In Europe, where people have neither grasped the role of the state in the US nor the role it should play in Europe, the neoliberals à la Merz and Lindner will take the radical reformers’ initiatives as an opportunity to blow their libertarian horn even louder.

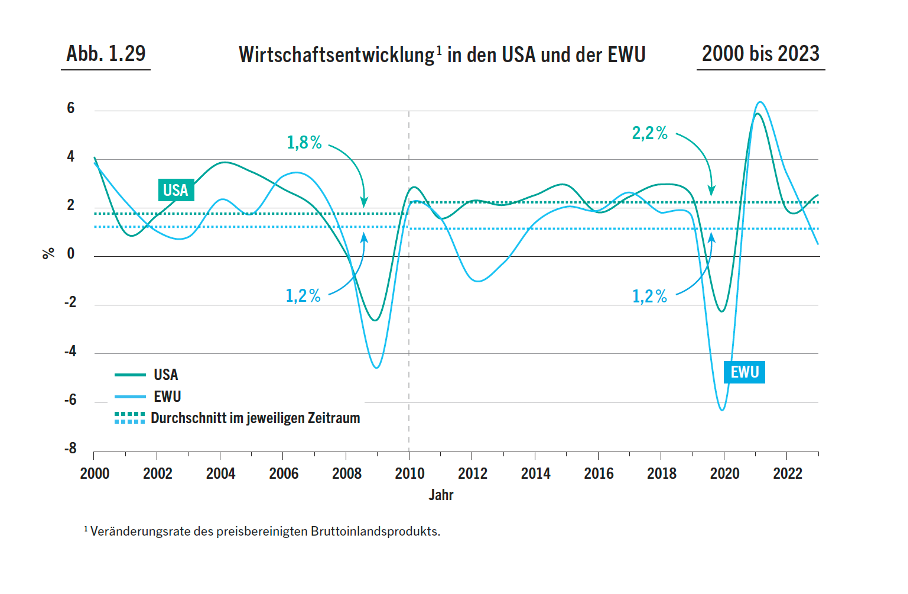

Europe has lagged far behind the US in the past two decades (as shown in detail in my new book, from which the image is taken) because the state there has played a role that would have been flatly prohibited by European norms. Looking at growth rates since 2010, Europe’s failure is obvious:

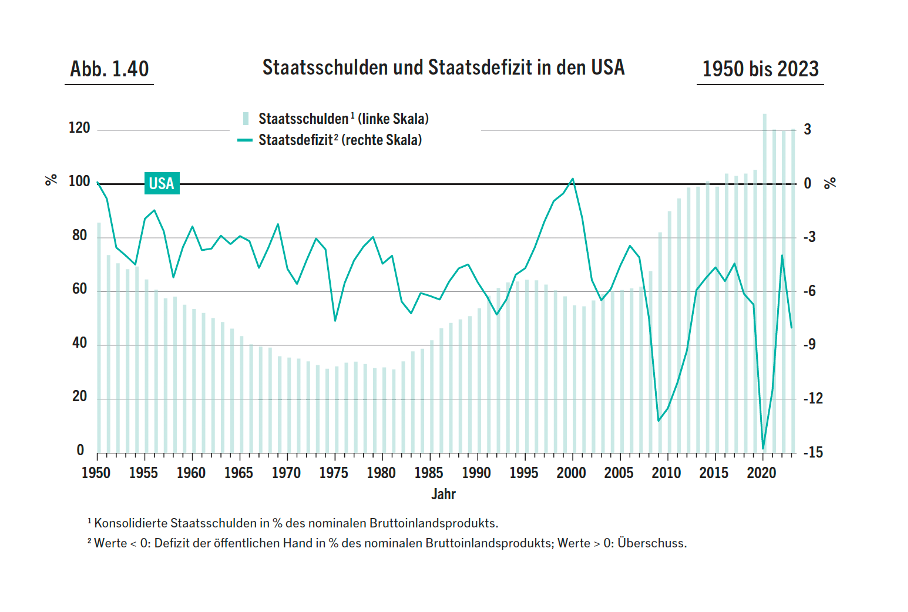

The US achieved an average increase in aggregate income of 2.2 per cent per year between 2010 and 2023, while the European Monetary Union managed just 1.2 per cent. In the US, as the second figure shows, public debt rose from 85 to 120 per cent of GDP over the same period, while in the EMU it stagnated at around 90 per cent. There can be no doubt that the increase in US public debt was both inevitable and the cause of America’s success.

Under the current conditions of saving and borrowing in the individual sectors of the US economy (explained here), there is logically no other way for the US to ensure a satisfactory development of demand than through rising government debt. Should the libertarian billionaires prevail and should the second Trump administration attempt to reverse fiscal policy, it would be the end of American dynamism and American superiority. In that case, however, one can assume that Trump will quickly chase the libertarians away and go back to borrowing, just as he did in his first term in office.

Under the current conditions of saving and borrowing in the individual sectors of the US economy (explained here), there is logically no other way for the US to ensure a satisfactory development of demand than through rising government debt. Should the libertarian billionaires prevail and should the second Trump administration attempt to reverse fiscal policy, it would be the end of American dynamism and American superiority. In that case, however, one can assume that Trump will quickly chase the libertarians away and go back to borrowing, just as he did in his first term in office.

Why are Europe and Germany so unreasonable?

The more conservative forces around Merz and Söder prevail in the upcoming elections in Germany, the more Europe will fall behind. If Lindner were to become finance minister again, it would be the worst case scenario for a rational fiscal policy. For Europe, economic incompetence is even more dangerous these days than it is for the US, because the US still has the outlet of foreign trade. If the second Trump administration were to succeed in significantly reducing the current account deficits through tariffs or a weakening of the dollar, this would provide some relief for the state. Europe can only lose out. Germany, with its still exorbitant current account surplus, would finally be brought to its knees.

But it is not only the conservatives; the German social democrats are also on the wrong track. The paper adopted by the party executive a few weeks ago states right at the beginning: ‘After two years without economic growth, very fundamental questions are at stake for our country. The competitiveness of Germany and Europe must improve in many areas. At the European level, the reports by Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta provide important starting points for this.’ The paper is also dominated by the idea of further increasing international competitiveness. The word “demand”, on the other hand, does not even appear.

All the talk in Germany and Europe about ‘improving competitiveness’ is nothing more than a hollow phrase, because there is no way to win a trade war against the US and the attempt to improve competitiveness with respect to China is doomed to failure anyway (as shown here).

But even if you don’t go down the German path of improving competitiveness, you still haven’t reached your goal. In Europe, there are still very different ideas about how to generate growth without incurring government debt. I was invited to a conference in Italy in mid-September, where I tried to explain the macroeconomic context, but it was in vain. The former social-democratic Prime Minister Enrico Letta spoke immediately before me and the conservative Italian Foreign Minister, Mr Tajani, spoke immediately after me. Both insisted on the idea that it would be possible to stimulate growth with an intelligent policy for small and medium-sized enterprises, which would cost almost nothing and then reduce the national debt..

This is also a topsy-turvy world. There is no way to stimulate the economy without solving the fundamental demand problem of today’s economies. In Italy, too, the entire private sector is, on balance, a major saver. Consequently, the country is under permanent recessionary pressure that only the state can remove by incurring new debt.

In the FAZ, the new French finance minister Armand recently said that reducing public debt has the highest priority for the Barnier government. But he did not say a word to suggest that he had ever heard of the relevant macroeconomic interrelations. On the contrary, when he says that cutting government spending is difficult because it has negative consequences for people, he shows that he is stuck at the level of the Swabian housewife.

He should have told the FAZ journalists, who have been stubbornly denying macroeconomic connections for years, that cutting government spending leads to exactly the opposite of what is intended. By reducing demand, it worsens the situation of companies and consequently the overall economic situation. But that worsens the state’s budgetary situation, not improves it. Cutting government spending of any kind is not ‘difficult’, it is nonsensical under the given circumstances.

Demand is the problem, not competitiveness

Large, largely closed economic areas such as the US and the European Union must be able to generate the demand they need to achieve full employment. It is foolish to act like a single entrepreneur who can force others out of the world’s markets by improving his own competitiveness when he is a huge part of that market himself. Consequently, the approach chosen by the European Commission, namely to task Mario Draghi and Enrico Letta with making proposals for improving European competitiveness, was misguided from the outset and an expression of the confusion at the top of the European Commission. The report by Draghi and Letta does not address the central issue of creating endogenous demand, although it argues in favour of more government spending and more European debt in its conclusions.

All those who insist that the supply side must be addressed in order to solve economic problems remain at the level of the business economist, the manager or the frugal housewife. They assume, usually without really knowing better, that there is no demand problem because ‘the markets’ ensure an efficient conversion of savings into investments. This is the crucial misunderstanding and the serious mistake of the prevailing economic thinking. This transformation necessarily assumes that the corporate sector, as in the 1960s, borrows and invests on balance. Anyone who fails to recognise that there has been a drastic change here since the beginning of the century, because companies are net savers, cannot make any competent statement at all.

It is truly grotesque how far the empirical findings on the state of the German economy differ from the findings discussed in politics. At the beginning of this week, the ifo Institute reported that the lack of demand in the German economy is currently almost as great as it was during the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. Over 40 percent of all companies are suffering from it. And capacity utilisation in the economy as a whole (see graph from the autumn 2024 joint economic forecast), which is also calculated by the ifo Institute, is approaching the levels reached during the major recessions of the past. But, as we know, ideology and political cowardice are not impressed by facts.