Hardly anyone noticed, but the spring report of the German research institutes finally states again what many have been waiting for: Germany’s export surplus is returning to its old strength after a year of weakness. As recently as the fall of 2022, the institutes believed that this year’s surplus (in this case the so-called net exports) would again be around 80 billion euros, far below the figure of 191 billion euros it had reached in 2021 (and in this order of magnitude in most previous years). Even in 2024, the institutes expected at the time, it would not exceed 84 billion.

It is possible to be so wrong. In their latest forecast, the institutes fundamentally revise their assessment of the opportunities for German exports on the world markets and now estimate that as early as this year, net exports will again show a surplus of 160 billion euros. For 2024, it is now even expected to exceed 180 billion euros, almost as much as in 2021. The Federal Statistical Office confirms the rapid revival of German export strength; in January and February of this year, an export surplus of 16 billion was achieved in each case.

Where does the forecast error come from?

If you look more closely, it’s easy to see why the institutes got it so wrong. The huge error in net exports has nothing to do with Germany’s export strength, but with another grandiose miscalculation on the imports side. As recently as the fall of 2022, the institutes expected the price of electricity and gas to peak only this year.In making their “assumption,” the institutions apparently were guided by the idea that the forward contracts that existed in the fall of 2022 for 2023 and 2024 would reflect likely developments in the next two years. Consequently, they assumed that wholesale prices would remain very high “in the coming months” and would only start to decline gradually in the spring of 2023. Futures contracts, it should be noted, however, have nothing to do with the future, but only with the expectations of some market participants, who can be just as wrong as ordinary citizens.

As the assumptions of the forecast in spring 2023 show, they were wildly off the mark. The institutes expected the average price of electricity in 2023 to still be slightly higher than in 2021, but gas and oil, according to the current assumption, will return almost to the values that applied in 2021, i.e. before the crisis. As a result, Germany will pay over 200 billion euros less for imports this year than the institutes expected last fall.

This misprediction in itself is not particularly important, but at least two significant conclusions can be drawn from it. The first is obvious: A country’s current account balance responds immediately and quickly to a marked change in the terms of trade, i.e. the price ratios in foreign trade. If the terms of trade fall because imported raw materials become much more expensive, the bill a country has to pay for these raw materials rises very immediately because it cannot do without their use in the short term, i.e. the quantities required cannot be reduced very much.

That’s obvious, many non-economists will say, what’s so special about that? Indeed, it is obvious, but for decades the vast majority of economists have tried to persuade us that current account balances have nothing to do with the prices of imports and exports, but are the result of capital flows, i.e., above all, of a country’s decision to invest surplus savings abroad or not.

Neoclassically oriented economists emphasize the importance of capital flows for the emergence of current account balances. The focus is on the autonomous decision of consumers to save more or less. Even economists who are considered relatively enlightened support the thesis that the emergence of current account balances depends on an economy’s “propensity to save,” i.e., high propensity to save equals current account surplus and vice versa. It is assumed that economies live below their means, i.e. that they earn more than they spend, because they have a high propensity to save. In contrast, economies with current account deficits are assumed to have a low propensity to save and thus a tendency to live above their means, i.e. to spend more than they earn.

Price Ratios in an International Context

One could easily test this thesis by asking how, then, the saving behavior of different countries can be reconciled at the global level. After all, there is no possibility for the world as a whole to save in the sense mentioned above, i.e. to spend less than it takes in. The world’s saving is always exactly zero.

If all countries of the world had the desire to be savers, in order to provide in this way for the future (like that in Germany with full earnestness as reason for the surpluses is presented), we must inform them unfortunately that this is impossible. All squirrels of this world can put back nuts, all countries cannot provide in this way for the future, however. If all countries in the world have similar savings plans, for example, a desire to save more to provide for the future, there must be one or more mechanisms to ensure that these savings plans, which are inconsistent when viewed from a global perspective, are brought into line with the logical need to establish an absolutely balanced current account for the entire world.

The struggle for current account surpluses (unlike all trade) is a zero-sum game for all countries in the world. So some countries must necessarily abandon the notion of building current account surpluses. But how do you get them to do so – against their stated will? Logically, it is absolutely imperative that only a mechanism which itself has zero-sum character, i.e. always takes from one what it gives to the other, can bring about this balance. The two most important mechanisms of this kind are changes in the terms of trade, i.e., changes in export prices to import prices, and, closely related but not the same, changes in export prices (expressed in international currency) to each other, i.e., what are called real exchange rate changes or changes in the competitiveness of countries.

Consequently, the first lesson to be drawn from the brief episode of a much smaller German current account surplus in 2022 is that the neoclassical theses on current account balances must be immediately and definitively shelved. If this had been known at the time of the euro crisis, Greece would have been spared much suffering.

Two temporary phenomena

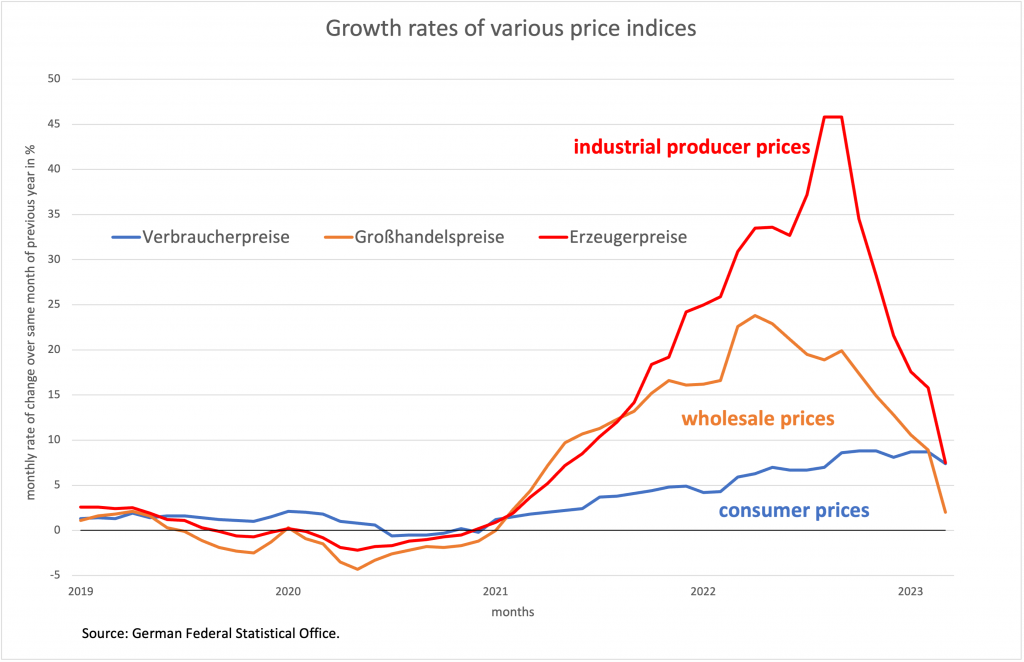

The second lesson directly concerns what has been commonly called inflation for the past year. This “inflation” was, this much is indisputable, the direct consequence of price increases for imports, especially for fossil fuels. However, if these price increases are clearly limited in time in terms of their impact on the German current account, they are also limited in terms of their effect on the rate of domestic price increases. Recent developments in wholesale prices and producer prices in Germany confirm just that. Both price indexes, which have a certain lead over consumer prices, have (as figure 3 shows) already moved or are moving very close to the ECB’s target of two percent.

Producer prices, even if they do not fall further, will fall below the 2022 level as early as July, i.e., they will show a negative rate. Producer prices for services have already fallen year-on-year in absolute terms in the fourth quarter of 2022. In the euro area, the year-on-year inflation rate fell to 6.9 percent in March, again with a clear downward trend.

Figure 3

In view of this, however, one has to ask why “inflation” is being given the impression by almost everyone involved, including the crucial institutions and economic policy, that it is a very dangerous and possibly persistent phenomenon that needs to be tackled at all costs by monetary policy and wage policy. The ECB and German and European policymakers should have made it clear from the outset that the price increases observed were not an inflationary process, but a one-off price increase which, moreover, had come from outside and had to be accepted by all those involved in order to avoid pointless conflicts of the kind represented by a price-wage price spiral.

But many “experts” have remained silent because they secretly believed that “inflation” was the result of excessively expansionary monetary policy over the past decade, which coincided with external price increases. That is why, on the one hand, people have not hesitated to recommend a tough response to monetary policy against all reason (as shown here), and, on the other hand, many observers have advised unions not to accept a real wage sacrifice under any circumstances. The decline in the terms of trade and the loss of real income for society as a whole, as shown in the decline in the current account, were mostly simply ignored (as shown here).

The fact that the most important relationships were as much misinterpreted in the third oil price explosion as they were in the two oil price shocks of the 1970s, casts a terrible light on professional economics. The discipline deals almost exclusively with equilibrium models and empirical methods such as econometrics, and has lost most of its understanding of dynamic macroeconomic developments. If ideological barriers are added, as is regularly the case with monetary policy and inflation, the published results no longer have anything to do with science. An economic and financial policy that does not have its own expertise and relies on the results of the prevailing economic theory is incapable from the outset of adequately meeting the many challenges it is faced with.