A few days ago, the Federal Statistical Office reported that the average inflation rate in Germany in 2024 was only 2.2 per cent. The harmonised rate used by the ECB was 2.5 per cent. According to an ECB estimate from December 2024, the (harmonised) inflation rate for the euro area for the whole of last year will have been 2.4 per cent. This is a result that is surprisingly close to the ECB’s target and shows that most of the forecasts made by seemingly well-informed sources on inflation trends were far too pessimistic.

But instead of taking note of this and asking themselves why they were so wrong, some of the press, driven by inflation phobia, such as the Handelsblatt, pounced on the 2.6 per cent published by the office for the month of December – even though the office explicitly pointed out that, due to methodological changes, the results are not readily comparable with those of November. There is a fatal tendency in certain media and on the financial markets to write up the risk of inflation because many financial market players expect higher profits when interest rates are high.

The figure for the year as a whole is interesting in that it shows how far institutions such as the German Bundesbank were from reality in their forecasts. In December 2022, the Bundesbank had predicted (see original Bundesbank chart) that the German inflation rate (harmonised rate) for 2024 would be 4.1 per cent. Even for 2025, the Bundesbank came up with an annual average of 2.8 per cent, a forecast that will be significantly undershot as early as 2024. At the same time, the expectation regarding economic growth was far too optimistic (1.7 per cent plus for 2024; in fact, it is close to zero).

Even in September 2023, the ECB was still expecting the inflation rate for 2024 to average 3.2 per cent. All estimates were significantly too high. This is disastrous, as it shows that the central banks have a severe bias towards inflation phobia. What’s more, the inflation phobia is being reinforced by many media outlets for maximum publicity effect, and politicians can hardly defend themselves against it because they are afraid of coming into conflict with the independent central bank.

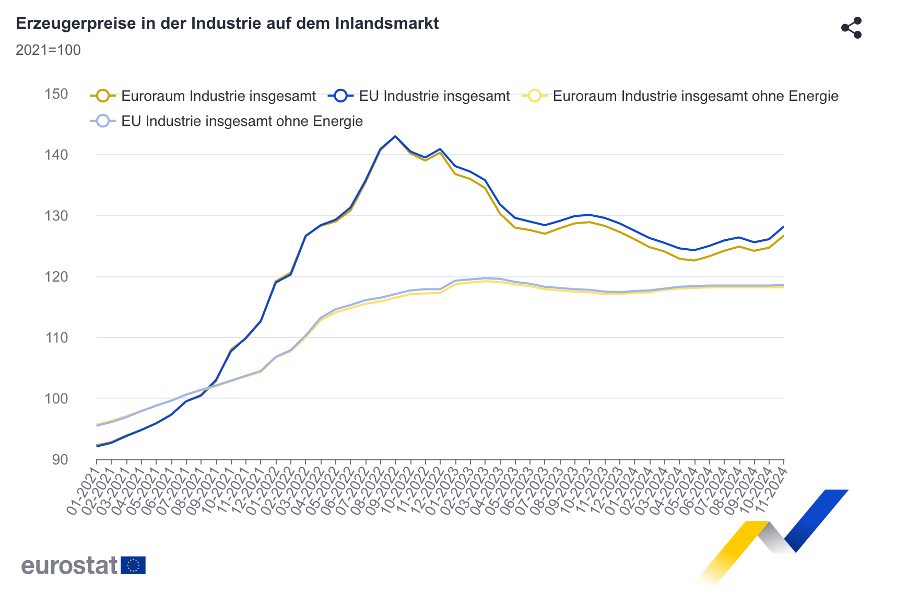

The ECB’s wait-and-see approach is extremely expensive for society because there really is no longer any risk of inflation. One of the best leading indicators for general inflation trends, industrial producer prices, are completely constant, i.e. they show a growth rate of zero if you exclude the strongly fluctuating energy prices. The figure from Eurostat shows that these producer prices (excluding energy, the pale yellow curve) have hardly moved at all from the beginning of 2023 to November 2024. Which means nothing other than that competitive pressure is so high that industrial companies have not been able to raise prices for almost two years, despite the fact that wages have been rising sharply of late.

Since industrial production and sales are declining across Europe at the same time (somewhat less in other countries than in Germany, but clearly declining), the (nominal) return expectations of companies in this sector are clearly negative on average. As can be seen from the development of real GDP in the euro area (which is growing at around 0.5 per cent), this is not offset by the other sectors either. The fact that a ‘neutral interest rate’ is being discussed in central bank circles, which could be around two per cent, can only be understood as an intellectual gaffe based on unsuitable models.

In the face of economic stagnation and an absolute decline in the areas that promise higher productivity and dynamic investment activity, an interest rate of well over three per cent from the central bank (companies have to pay even higher interest rates to their banks) has an enormously restrictive effect; it inevitably leads to a drastic reduction in investment activity, as we are currently experiencing. Even a further slight interest rate cut, which is expected in 2025, will not change this situation for the time being. Two per cent is still restrictive and by no means ‘neutral’.

This is where the rest of economic policy comes into play. The only thing that helps when production is stagnating or even falling and interest rates are too high is a general revival of demand to improve return expectations across the entire economy. This is only possible through government spending financed by new debt. Everything else is window dressing and merely shifts money from one pocket to the other. Only spending that is not ‘financed from the opposite direction’ (by cutting government spending or raising taxes) can have such an effect. The term ‘financed from the opposite direction’ means that, due to the drop in demand, corporate profits are reduced by the amount that is being attempted to be saved.

All this is about global control. There is no need for economic policy to worry about any individual company. Correcting management mistakes is impossible anyway and counterproductive. There is also no point in counter-financed subsidies to reduce electricity prices or investment bonuses, because neither can ever have an effect on the economy as a whole.

Since no decisions are expected before the election at the end of February and it will take a long time afterwards before a government is formed that is capable of economic action, only lucky coincidences can prevent Germany from stagnating to the maximum for the third year in a row. With the wrong monetary policy, the state can turn itself upside down, but it will not succeed in initiating an economic turnaround for the better with all the measures currently being discussed across party lines. Only with a very large debt club, as the US is demonstrating, could the state overcome the restrictive monetary policy. However, this is practically out of the question due to German confusion about the meaning and role of state debt (as shown, for example, here).