On 9 December last year I wrote that Germany is in recession, while economic and financial policy imagines that things can only go up. Since then, endless nonsense has been written about winter recessions, technical recessions and the like. Economic policy has been able to hide behind this whitewashing by the media. Now Germany is in the midst of a severe recession and it will not be easy to stop the downward momentum because politicians have still not recognised the signs of the times.

The day before yesterday, the Federal Statistical Office reported that new orders in German industry fell again in April, following an outright slump in March. To cite just the most prominent example and Germany’s flagship industry: In mechanical engineering, new orders have now been declining steadily since autumn 2021. In the third quarter of 2021, the index level (2015 = 100) was 125. After six consecutive declines in the past six quarters, the index is now, in April 2023, at 92. This is a real debacle and shows how absurd the hope of the government and official advisers is that there could be upward investment activity by companies this year.

In order to assess the severity of the threat posed by the domestic economic downturn, one must always take into account in Germany that positive impulses are once again coming from foreign trade. The German current account will return this year to the surpluses achieved before the commodity price explosion, and yet this will not be enough to avert a possibly prolonged crisis as the domestic economy slows down.

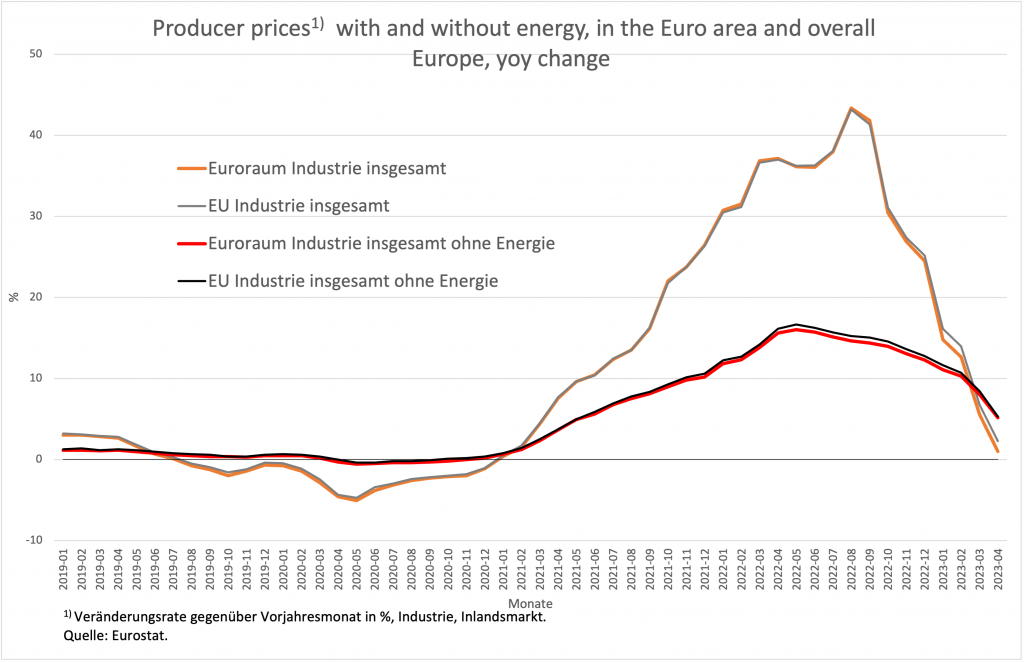

At the same time, Eurostat reports that producer prices in the European Monetary Union (EMU) fell by 3.2 per cent in April compared to the previous month. The index is thus more than nine per cent lower than in September 2022, the peak of the wave of price increases. Compared to April 2022, industrial producer prices rose by only 1 per cent in the euro area in April 2023. An absolute decline even compared to the previous year’s value is only a matter of one or two months.

Figure 1

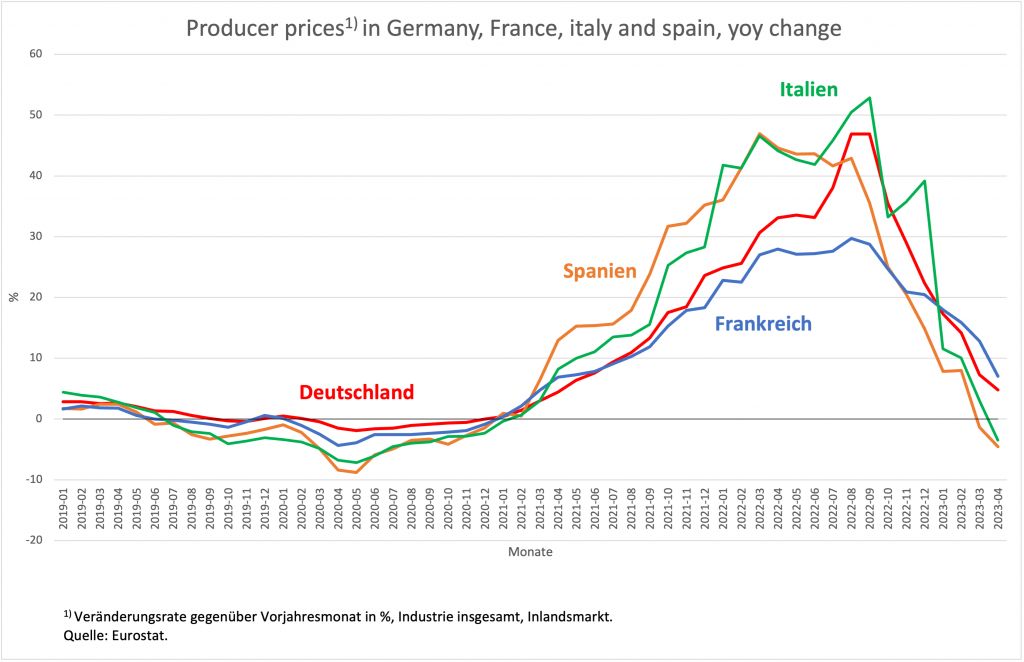

In Italy and France, the month-on-month declines were downright dramatic at 5.1 and 6.5 per cent, respectively. However, while France is still up seven per cent year-on-year (Germany was up 4.8 in April), Italy is already down 3.5 per cent even in this comparison. Spain also records a year on year value of minus 4.5 per cent, which is a clear indication of where the rate of price increases at the consumer level is heading. In Spain, this “inflation rate” was last measured at 2.9 per cent, already very close to the ECB’s target.

Figure 2

Both the massive economic slowdown and the price development show how inappropriate the approach of economic policy, including European monetary policy, currently is and, according to everything that has been announced so far, will also be next year.

Fiscal and monetary policy from another planet

German fiscal policy seems to have completely abandoned taking the economic situation into account in its decisions. The Federal Minister of Finance acts as if the abrogation of the debt brake in the crises of recent years was the reason and justification for having to comply with the debt brake regardless of the economic situation, i.e. even if the German economy collapses in 2023 and possibly also in 2024. However, there is no economic law that says that several crises are automatically followed by a recovery. If economic policy makes big mistakes again, the crisis will continue unabated. The idea that we now have to return to state precautionary savings in order to be able to draw on the reserves (in the form of a lower level of government debt once again achieved) for exogenous crises is absurd, when it is precisely this precautionary saving that fuels the crisis.

Christian Lindner has summed up the government’s collected confusion on economic policy issues in two short pithy sentences. In an interview he said, “In times of inflation, rampant new debt would be irresponsible… we (would) delay fighting inflation.” But, firstly, there is no inflation, secondly, it is never a question of “rampant new” debt, and, thirdly, new debt would prevent a recession, but under no circumstances would it delay or even challenge the decline in prices that is already underway.

Even with the phrase “in times of inflation”, the Federal Finance Minister proves his complete cluelessness. He, too, obviously believes in the horror story that economists of the calibre of Hans-Werner Sinn put into the world, according to which the ECB and government debt were ultimately responsible for “inflation”, even if the trigger was a different one. With this diagnosis, so much is already clear today, the Federal Minister of Finance will do enormous damage to the country entrusted to him and far beyond.

This applies equally to those responsible at the ECB. Look at the speech the president of the German Bundesbank gave at the University of Bochum on 5 June and you will see where the ECB’s grandiose misjudgement comes from. At a time when it is obvious that the forward-looking inflation dynamic is completely broken, even threatening to turn into a deflationary one, the president said:

“Underlying price pressures are … far too high, and they are hardly receding so far. In May, core inflation (excluding food and energy) is likely to have been 5.1 per cent in Germany and 5.3 per cent in the euro area. Therefore, monetary policy must not and will not let up in the fight against inflation. We must be even more persistent than the current inflation.”

This is not merely wrong, it is crazy. A May year-on-year growth rate is no measure at all of inflationary pressures, of what might be coming. You have to look either at current rates, that is, month-to-month movement, or at prices, which, like producer prices, have a lead before consumer prices and what is called core inflation. How, when you are in such a position, can you just keep the public in the dark about the real forward looking indicators like current consumer or wholesale prices? Obviously, the aim here is to obscure one’s own failure to adequately diagnose inflation.

The most problematic thing about the analysis of those responsible, however, is that it does not in any way appreciate the reasonableness of German wage policy. The wage settlements that have been made since the price spikes are aimed at cushioning the strong increase in the price of essential goods (food and energy) as much as possible for the lower wage groups and at imposing the indisputable macroeconomic real income loss more heavily on the upper wage groups. This approach prevents the imported price surges from turning into a sustained higher rate of price increases. Therefore, the desired rate of price increase of 2 per cent will come about again by itself, without monetary and fiscal policy first having to bring about a recession, which would again particularly endanger the less well-off.

The contradictory nature of the experts’ assessment of the situation becomes clear when, parallel to the warning of high core inflation, they state that private consumption is stagnating – as, for example, the outlook of the German Bundesbank in its monthly report of May (page 10). If this is the case, where does consumer restraint come from? Obviously from the fact that real wages are falling, which logically rules out the threat of an acceleration of inflation on the part of wages.

Monetary policy would have every reason to respond to wage policy rationality with an investment-friendly interest rate policy. If it does not see itself in a position to do this because in some European countries wage policy assumes less macroeconomic responsibility than in Germany, it should urgently seek dialogue with the wage bargaining parties there. But apparently the necessary slaughter of the sacred cow called monetarism is an insurmountable obstacle. It prefers to use “inflation expectations to be anchored” as a justification for tightening monetary policy in the middle of the downturn and thus risking a Europe-wide recession.

If, because of disregard for the role of national wage policies, unit labour costs in EMU and the EU diverge again as they did in the first decade of monetary union (where Germany was the biggest sinner), there is a threat of widening trade imbalances once more. It is irresponsible to bemoan the inevitably resulting high government deficits and then declare them the cause of renewed tensions within the E(M)U. This policy will not only reduce the already large wage imbalances in the EU, it will also increase the risk of a recession. This policy will exacerbate the already high tensions in Europe and increase bitterness about Germany’s attitude.

Indeed, it looks as if the ECB will raise interest rates again next week. That would then be the ultimate proof that the ECB leadership has lost all scale under pressure from the northern countries and is forcing Europe into a recession that will have enormous political consequences. Not only in France, Italy and Spain, but also in Germany, nationalist political forces are pushing forward who have no promising recipes themselves, but who “know” very well that all evil comes from Brussels. These forces will promise the citizens exactly the economic upswing that the ruling parties and a misguided ECB cannot deliver, because they have no macroeconomic concept, get tangled up in misdiagnoses and waste all political energy on side wars.