I have been observing the German economy very regularly for almost 50 years. What is currently happening has never happened in Germany in this long time: The economy is in a long and severe recession, but politicians don’t want to admit it. They deny what is obvious because they suspect that no political constellation can be found with which a consistent policy to combat the recession could be implemented. As a result, some are talking about “deindustrialisation”, others about a “shortage of skilled workers” and third parties – once again – about the unwillingness of recipients of state aid to take up work.

In the past, such political statements could be described as false diagnoses in a phase of economic weakness, but today they are simply ridiculous excuses because no one has the courage to say that almost all political forces together have manoeuvred Germany into a dead end and can no longer find the way back.

The economic situation is bad

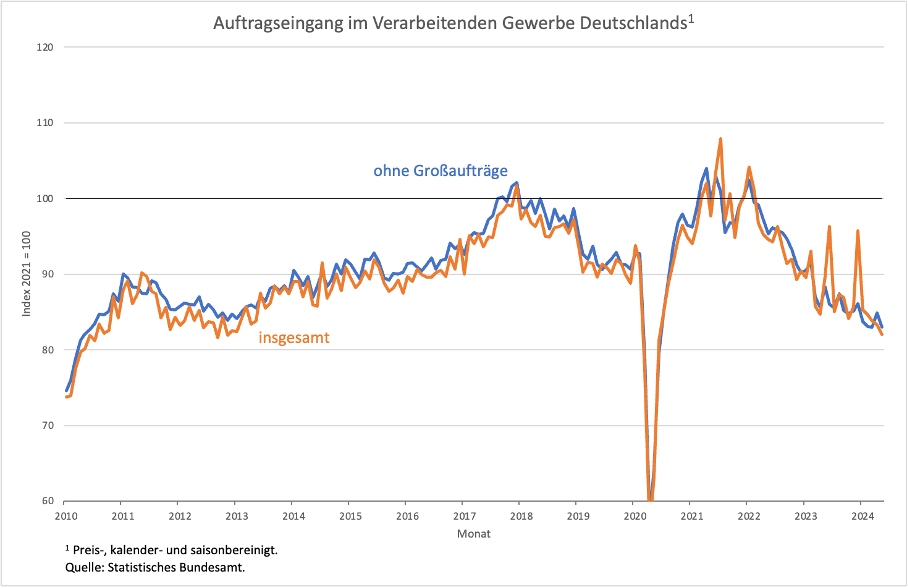

The economic situation is easy to describe. One of the most reliable indicators of economic development is incoming orders in the manufacturing sector (Figure 1). The numbers here have been pointing clearly downwards since the start of 2022. That is now almost two and a half years. The index left the one hundred mark in the first few months of 2022 and, after a long downward journey, landed at just over 80 in May 2024. If we add to this the fact that the latest survey results for July all continue to point downwards, we can expect the 20 per cent decline in incoming orders to be reached in the near future.

Figure 1

This applies to both domestic and foreign demand. Those who continue to gloss over the situation and hope for a miracle, as the Federal Minister of Economics is still doing, are wasting valuable time, because in the not too distant future, weak demand will destroy entire industrial sectors that will never be able to recover. This is already clearly evident in the announcement by many companies that they will be significantly reducing their workforce. But it is also evident in the labour market as a whole, where the number of unemployed persons has been rising by around 20,000 per month for some time and the number of vacancies on offer is falling by around 10,000 per month. But this is not being discussed either, because it would immediately reveal how absurd the discussion about a shortage of skilled labour or even a general shortage of labour is (as claimed here by the ECB leadership).

One of the biggest mistakes of our time is probably the belief that we can largely ignore cyclical fluctuations of the economy because things will pick up again sooner or later. However, a long economic downturn leads to a permanent loss of income and reduces an economy’s ability to invest and offer highly productive jobs. Structural problems and weak investment are usually the result of a lack of dynamism in the economy as a whole, which has its origins in the failure of policy during periods of economic weakness. Anyone who has a debt brake in the Constitution and has to comply with a dysfunctional European debt rule is on extremely shaky ground from the outset.

The political situation is tricky

The reasons for the recession are obvious. The European Central Bank wanted to create a weakness in demand in order to combat inflation, which it saw as essential – and it succeeded. The country that is most dependent on investment demand in Europe and the world was hit the hardest because high interest rates are poison for investment activity. Although the “inflation” is long gone because it was only a one-off price spike and not a dangerous “inflation”, the ECB (see the Schnabel interview linked above) is clinging to clumsy attempts to justify its wrong decisions and is thus delaying the return to an appropriate interest rate level.

Politicians generally find it difficult to criticise the independent central bank because they believe that any criticism from their side will be seen as an attack on the central bank’s independence. But politicians could have the courage to engage. They could exert a much greater influence on the general discussion of economic phenomena if they were involved in it with a high level of expertise both in and outside the public arena. But expertise is missing. As a result, the central banks are not only left to make the decisions, but also to dominate the entire discussion. This cannot be meant by independence and frustrates citizens because there is never a serious attempt to explain economic development and its consequences.

But even beyond monetary policy, the political situation is tricky. The Federal Minister of Economics has said this most clearly. He knows that the coalition agreement of the ruling coalition contains the wrong course in terms of fiscal policy and the debt brake. However, he believes that it will still be possible to make ends meet if the coalition partners agree on many small measures on the supply side that cost practically nothing, as in the latest growth package. This is a mistake. You can turn hundreds of small supply-side screws without the economy moving a millimetre. As long as the fundamental interest rate problem has not been solved or covered up by massive government demand policy (as in the USA), any attempt to move the world by turning small screws is doomed to failure.

That’s exactly what you have to put on the table if you want to have an enlightened debate. Pretending that there are simple and “cheap” alternatives to government demand stimulus blocks the absolutely necessary debate on the debt issue (which is explained here). It directly supports the position of those who, like the minister of finance Christian Lindner, do not know and do not want to know the macroeconomic relationship between savings and debt because it does not fit into their ideological world view.

It is also more than astonishing that Habeck believes that his party can convince voters to vote Green in the next federal election campaign with better arguments on the issue of public debt. But how does he intend to convince citizens, especially during the election campaign, who have been fed for decades by him and the majority of other parties with the argument that demand policy via government borrowing can be replaced by “growth packages” with hundreds of small and very small measures? He will not succeed in initiating a comprehensive debate on debt because the mass of the population in Germany is simply not prepared for it. What’s more, even after the next general election there will be no majority in parliament that takes a non-ideological position on debt. The Christian Democrats are at least as stubborn as the liberal FDP on this issue, but without them it will in all probability not be possible to form a government.

No, the way out of the impasse will not fall from the sky. Only if enough sensible people in Germany were to come together to subject the debt issue to a rational review could there be governments in the future that would not gamble away Germany’s future as recklessly as the current one. Is that to be expected? I don’t think so. Germany and Europe are heading for a dark economic future.