Continuous fire from all media sources, as can be seen in many examples these days, develops a life of its own at a certain point that is difficult to control, because even rationally thinking and working contemporaries are not unimpressed by it. In the wake of media indoctrination, people almost sleepwalk into dangerous but supposedly unavoidable paths because no one dares to call out loud and audibly “stop”.

This also applies increasingly to the danger of inflation in Europe, which is painted on the wall hundreds of times every day. Whereas a few weeks ago at least the ECB was still able to keep its head above water to some extent, now reason is slowly going down the drain there too. The bank’s chief economist, Irishman Philip Lane, now feels compelled (in the FT) not to rule out rising inflation expectations and signals a possible “normalisation” of monetary policy.

The German member of the ECB Executive Board, Isabel Schnabel, believes that one cannot keep the rise in house prices out of the inflation calculation (which might be difficult to justify), and the president of the ECB, Christine Lagarde, now also considers the risks of inflation to be greater than the risks of deflation. Because the president of the Bundesbank assumes a four per cent inflation rate for Germany this year, the new chief adviser to the federal finance minister believes that the trade unions will raise their wage demands accordingly and that the risk of a wage-price spiral is therefore great.

What has happened?

All this is more than astonishing. We actually know exactly what has happened. Yet almost everyone pretends that there are great mysteries surrounding the explanation of the current inflation rate. The individual prices behind the increased inflation rate, on the other hand, we understand without further ado. This is what the German Federal Statistical Office, to name just one example among many, wrote a few days ago:

“Supply bottlenecks, shortages of raw materials, increased demand at home and abroad have had an impact on the construction sector: Construction has become significantly more expensive in 2021. … the producer prices for individual building materials such as wood and steel have risen more strongly on average in 2021 than at any time since the survey began in 1949. For example, solid structural timber became 77.3 % more expensive than the previous year’s average, roof battens 65.1 %, and structural timber 61.4 %. Even the prices for chipboard, for which the waste product sawdust is usually used, rose by 23.0 %. By comparison, the producer price index of commercial products as a whole increased by 10.5 % on average in 2021 compared to 2020.

Not only the increased timber prices, but also the steel prices drive up the costs in construction: reinforcing steel in bars was 53.2 % more expensive on an annual average in 2021, reinforcing steel mesh cost 52.8 % more than in 2020. Among other things, reinforcing steel is used in shell construction to reinforce floor slabs, ceilings or walls. Metals were 25.4% more expensive overall in 2021 than in the previous year, which is likely to have an impact on construction projects. For example, semi-finished products made of copper and copper alloys, which are used for heating construction or in electrical installations, became 26.9 % more expensive than the previous year’s average.”

There is nothing mysterious about this: for reasons that are difficult to understand in detail, but which have to do with the production stops in the wake of the Corona crisis, there have been massive shortages of certain inputs for construction production and for other important industrial sectors. This raises the price index first at the producer level and then at the consumer level. The result is commonly and lightly called inflation, but it is only an expression of the fact that in a market system prices signal scarcity. Normally, we trust the efficiency of individual markets in such processes and do not expect the state to intervene.

This is compounded by significantly higher prices for agricultural products and, most markedly, for energy. Both gas and oil have become much more expensive, even if oil prices are still quite a bit below their historical highs. There may be shortages here too, but we know very well that speculation plays a major role in oil prices, as in most commodities.

You almost never hear anything about this in the German media, but a serious newspaper like the English FT reports about it again and again. If continental Europeans took off their neoliberal blinkers, it would be as obvious as the physical shortage. Speculation can be fought, but to do it with rising interest rates is completely absurd because you would have to raise interest rates massively and the collateral damage would be immense. Proposals for tighter regulation of these markets have been on the table here for many years and could easily be implemented with the necessary political will.

Nothing can be done immediately in the short term against the shortage of some goods in the wake of the Corona shock, which is completely new and probably unique for the global economy. One can only hope that these shortages, because they bring enormous and unexpected profits for the producers of these products, will be quickly eliminated. The old and new producers will try to earn a share of the boom by expanding the supply as much as possible through new investments in new production facilities. Any tightening or normalisation of monetary policy would already do damage at this point because investments would be jeopardised.

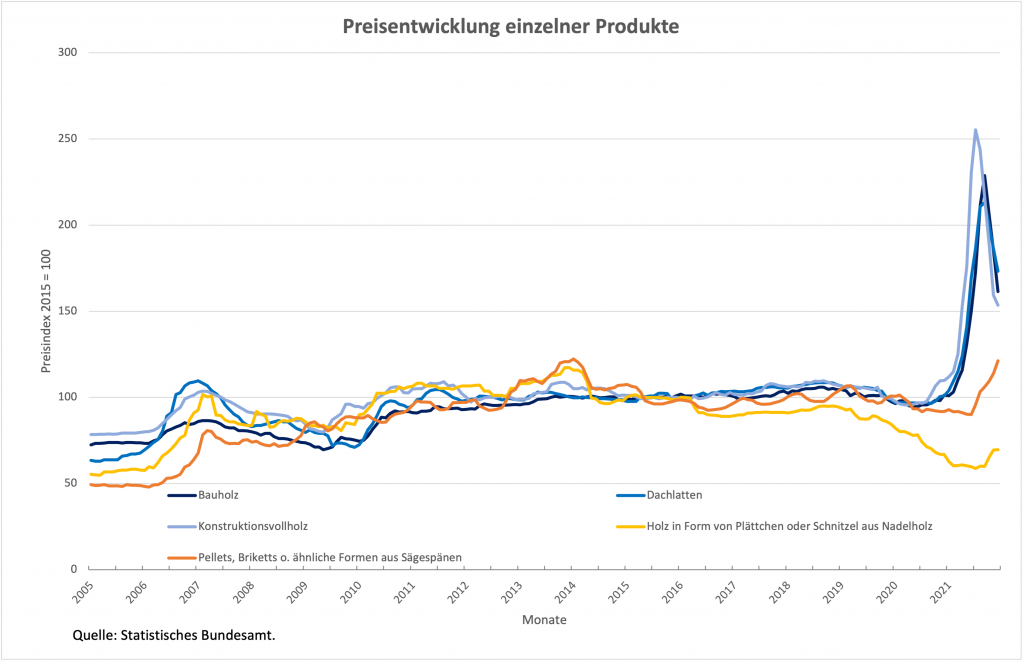

We also know that such price-driving scarcity effects are not permanent for purely statistical reasons. Some prices have already passed their peak, such as the prices for the wood products mentioned above (Figure 1). It would be more than astonishing if the prices of these products were to rise again next year far above their current level. Only then would there be a continuation of inflation, because the fall in prices – even from a very high level – means a fall in the inflation rate next year as well. The higher prices currently rise, the more certain one can be that there will be no continuation of high inflation rates.

Figure 1

Who has to bear the burden?

At the national level, only individual groups can be completely exempted from the burden of shortages as well as speculation-induced price increases, which are an almost global phenomenon. The state can undoubtedly relieve the poorest in society, but society cannot spare large groups such as workers as a whole the adjustment to the increase in the cost of living, especially not to the increase that comes from outside. The state has a variety of possibilities to help quickly and unbureaucratically those who, measured by their income, are hit the hardest. But it is also possible in collective bargaining to ensure that the lower income groups receive larger increases and thus the income pyramid is compressed.

If, on the other hand, workers were to make a blanket attempt to exempt themselves from the adjustment and pass on all the burdens to employers, this would not succeed. Employers are always able to successfully defend themselves by responding to rising wages in turn with rising prices. But why should trade unions, which until recently have not even been able to enforce the ECB’s inflation rate of 2 per cent, suddenly be able to translate much higher price increases, for which German employers are only partly responsible, into higher nominal wages?

In addition, the German and other European trade unions should have learned in the 1970s that even success in achieving higher nominal wages is a double-edged sword, because it is precisely this “success” that conjures up the case where the central bank – rightly – stifles the economy with rising interest rates and forces rising unemployment, with the result that trade union opportunities are considerably restricted. Who would be helped by this?

Unemployment in Europe, even if economists like Lars Feld simply do not take note of it, is still very high. Immediately after the Corona shock, the trade unions are weaker than ever. The DGB’s position (The Confederation of German Unions) on this discussion then does not sound like a declaration of war, but rather like whistling in the woods:

“It is also more than understandable when trade unions point out in collective bargaining that real wage losses – i.e. wage increases below the inflation rate – are unacceptable in the medium term. In view of the high average profits, companies can finance significantly higher wages without having to raise prices again. DGB-Klartext (No. 07/2022, Inflation: Draw the right consequences instead of the wrong conclusions)

The trade unions should not point to something they could not prevent anyway. They should rather say that their own renunciation of the two per cent tolerated by the ECB in the past was a big mistake, because they will probably never be able to compensate for the change in distribution to their disadvantage that this entailed. They should therefore insist that political help be given to ensure that from now on at least the two per cent is taken as a given in collective bargaining and that only the part corresponding to the national increase in productivity is negotiated.

The inability to talk to each other

The blame for the unclear role of the central banks in the economic policy assignment have to take primarily the mainstream economists. They have taught laymen like the new German finance minister that inflation expectations must be “anchored” in order to be harmless. He surely doesn’t know that this is just a dark and not very useful term that the dominant economists use to create the impression that there is a competitively organised labour market where people don’t talk to each other under any circumstances, but where the central bank sends signals that the trade unions and employers must obligingly take up, without there ever being a chance to talk sensibly to each other.

Economists have made a big fuss about inflation expectations and persuaded central banks that all they have to do is communicate clearly what inflation rate they are aiming for and most problems would be solved. The fact that central banks cannot achieve the inflation rates they set as their targets over a long period of time could have been understood during the past deflationary phase. All we had to do was draw the right conclusions and we would not be so speechless today.

Now it is taking its revenge that the ECB never clearly stated that in the medium term, i.e. the period that ultimately matters, the rates of price increases are mainly determined by unit labour cost increases and that without a sensible wage policy no sensible price policy can be pursued. The ECB should have conceded that in times like these, when the central bank is obviously totally overwhelmed in achieving its goal, it is not a matter of showing harshness, but of entering into dialogue with the bargaining parties in order to avoid conflicts that arise from speechlessness.

For good reason, the “Macroeconomic Dialogue” was once founded in the EMU, where the collective bargaining parties, politicians and the central bank can sit together to discuss current problems. It would be the task of the EU Commission to activate this dialogue immediately and to ensure that all important arguments are put on the table. If the trade unions and employers could currently trust that the ECB would not initiate an ill-considered period of restriction, they could, for their part, without any loss of face or autonomy, pledge that they would continue to stick to the ECB’s previous inflation target in their negotiations. But the EU Commission, especially under its current president, is failing on almost all fronts.

If policymakers take the fight against climate change seriously, they will have to learn to communicate. It will have to explain rising fossil fuel prices to society, along with the impact on price levels, and at the same time smoothly ensure that it is not the weakest who are burdened the most. If there is a Babylonian confusion of language about “inflation” every time, as is the case at present, it will hardly be possible to win over the majority of society for this. The question of whether the ECB can get by with its two-percent target if it pursues a consistent climate policy also needs to be clarified quickly, but without ideological reservations. But that is a new topic.