Sometimes it is incredibly difficult to draw clear conclusions from simple facts because people have become so firmly entrenched in a particular world view that anything other than this picture does not exist. If, for example, a member of the ECB’s Executive Board were to take a closer look at the USA, they would be astonished to realise that a decline in inflation rates has also set in there, which, if you believe in the ECB’s theories, should not actually be happening.

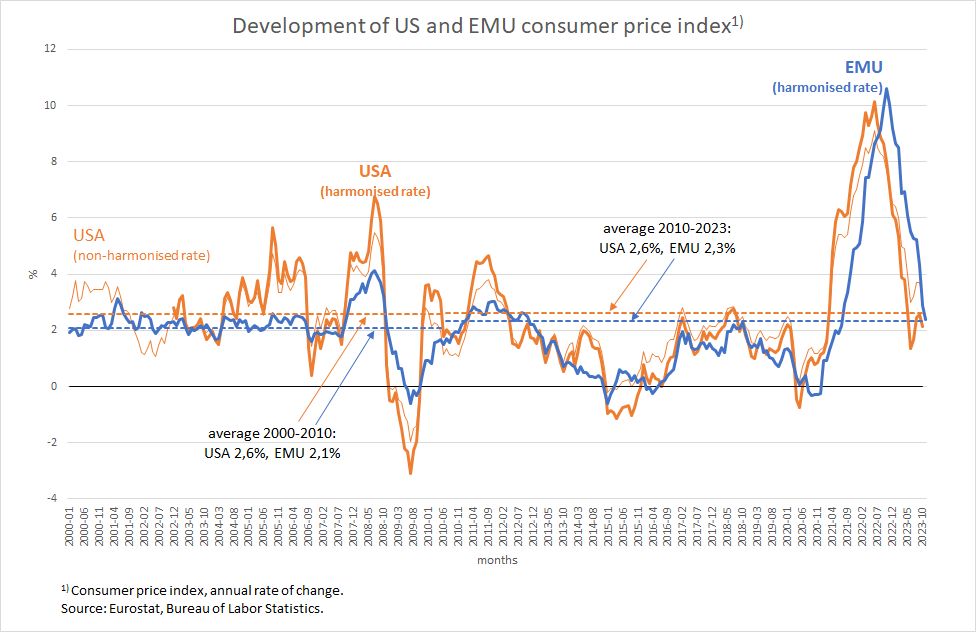

As the chart shows, the harmonised inflation rate in the USA was already close to two per cent in October of this year and thus even slightly below the figure of 2.9 per cent measured for the eurozone in October. The eurozone only reached 2.4 per cent in November. The ups and downs of the two curves have also been incredibly similar throughout the rest of 2020. That is more than astonishing.

Figure

Why are the inflation rates in the USA and Europe moving so similarly? Almost all observers in Germany, including some members of the ECB Executive Board, believe that European “inflation” has its deeper causes not in the energy price crisis, but in the ECB’s zero interest rate policy of the past ten years, the strong increase in the money supply, the inflation of the ECB’s balance sheet and the “debt orgies” of the European economies. If this were the case, it would be hard to see that the US is largely in line.

Even more astonishing, however, is the fact that the ECB’s leadership remains firmly convinced that only its restrictive policy has made the rapid return to rates in the region of 2 per cent possible. The restrictive monetary policy is having an effect, says Isabel Schnabel, a member of the ECB’s six-person management team (quoted from Handelsblatt). The ECB’s policy is helping to dampen demand growth. And this phase is necessary for inflation to move back towards the central bank’s two per cent target.

In Europe, according to this idea, it was therefore necessary to dampen demand growth to the point of recession by raising interest rates (in the third quarter, the European economy contracted slightly by 0.1 per cent compared to the previous quarter) in order to see rapid success on the inflation front. But what about the USA? There can be no talk of a recession there. In the third quarter, the economy there expanded at a record-breaking rate of 5.2 per cent (quarterly rate compared to the second quarter of 1.3 per cent annualised).

Although interest rates were also raised in the USA, there was no visible restrictive effect of the interest rate policy because the government is still countering this with an extremely expansive fiscal policy and private consumption is doing very well with average wage increases of over 5 per cent.

Could it be that Europe needs a recession to return to normal inflation rates and that the USA is experiencing the same price trend even with strong growth? No, it can’t be. The ECB leadership’s theory is wrong. Europe would not have needed a recession either, because the price rises were temporary and, given the global situation and global commodity price trends, have retreated evenly everywhere.

The ECB was correct in its assessment at the very beginning of the commodity price shocks, but cancelled it under public pressure (especially from Germany) and adopted the wrong theory. Now all those responsible for this mistake believe it is enough to rant about inflation for a while longer to deflect responsibility. This is fatal because there will be many victims of this vanity in the form of unemployment. After all, we have not yet seen the full impact of the interest rate policy on the European economy, but in all likelihood it is still to come.

The ECB itself expects its policy to take four to eight quarters to take effect. However, only a good five quarters have passed since the start of the interest rate hike. And the interest rate hike itself is historically unprecedented in terms of its speed and scope – the reference to the fact that the absolute interest rate level is much lower than in previous periods is of no use. In the meantime, companies’ price expectations must be predominantly negative because prices at the producer level (even excluding energy) are falling from month to month. This means a very high and even increasing interest burden.

But the Frankfurt ivory tower is so far removed from reality that nobody is interested in this looming danger. They apparently believe that announcements such as Isabel Schnabel’s that they can imagine no further interest rate hikes are proof of how empirically orientated and flexible they are in their decisions at all times. Viewed in the light of day, however, this is a retreat in instalments, which in turn causes further damage. The only right thing to do would be to admit the mistake made so far and at least not let its consequences get any worse by immediately cutting interest rates.