A simple series of figures made available recently by the Federal Statistical Office of Germany brings it to light: what has been called “inflation” in public in recent months will, according to all we know, only exist for a few more months at most.

Despite all the controversy about “inflation”, it is agreed that it is a phenomenon in which prices continue to rise rapidly. Consequently, the rate of inflation, i.e. the rate of increase in prices over a previous period, is so high that official targets such as the ECB’s two percent are exceeded.

It is not clear what exactly is meant by the “previous period”. One can take the ”previous period” to mean the previous month of the same year or the same month a year ago. Usually, reporting on price developments is based on a comparison with the same period of the previous year, the so-called annual rates of change.

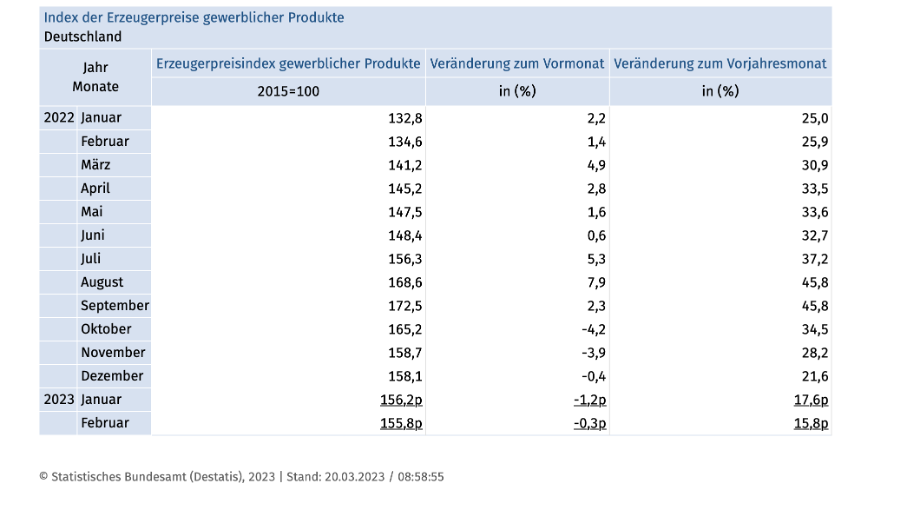

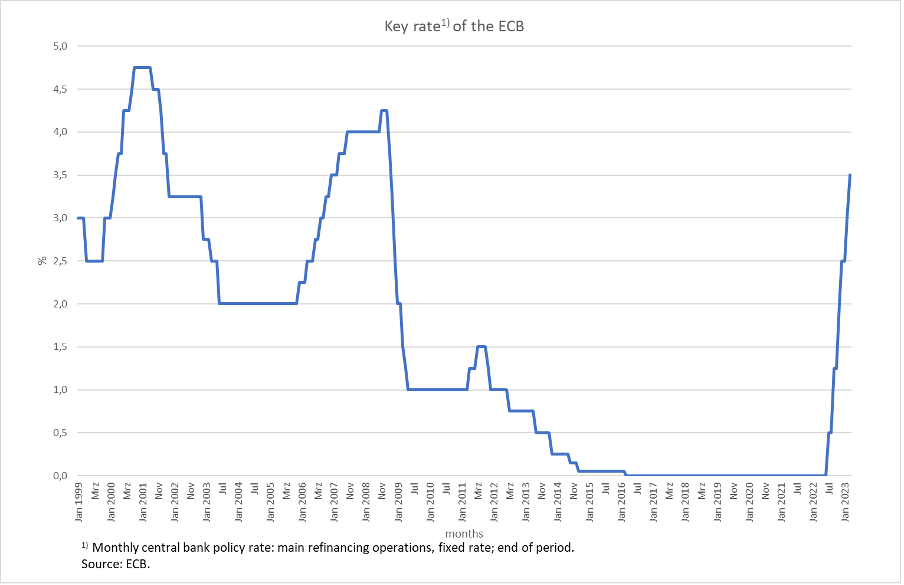

In the table of the German Federal Statistical Office on the development of producer prices (see below), both time series are shown – the rate of change compared to the previous month (the so-called monthly rate of change in the middle column) and the rate compared to the same month of the previous year (in the column on the far right). The column on the left shows the absolute level of producer prices as an index, as measured by the Office. The values marked “p” are considered provisional because the Office is still receiving further information after its initial calculations and will later include it in the statistics.

The previous peak of the price index at the producer level was reached last September. Since then the index has been falling, which results in monthly rates becoming negative since October 2022. Currently (February 2023), there was still a slight decline of 0.3 percent.

When calculating the annual rates of change (third column) the slowing down also becomes visible: the measured rates are still very high (most recently 15.8 per cent), but they are only a third of the values compared to late summer 2022. The calming of the trend in producer prices will be reflected in a sharp drop in the annual rates in a few months. In order to show this we have updated our calculation from a few weeks ago. The scenario we employ is based on the assumption that from now on prices at the producer level will remain absolutely constant, i.e. that the previous price reduction will not continue.

A clear perspective

The red area of Figure 1 shows the fictional development of the two growth rates for the rest of the year: the monthly rate (dashed line) is manually fixed to zero beginning in March 2023 and the annual rate (solid line) is calculated under this assumption. It falls enormously fast: in March the annual rate would only be ten percent, in July already slightly below zero and in September minus ten percent. For 2023 as a whole this would result in an average growth rate in producer prices of 2.2 percent compared to the average of 2022 (dotted red line).

Figure 1

Of course the producer level is not yet the consumer level. But there is no doubt that such a development will affect consumer prices with some delay. In any case, it can already be said today that without further new shocks there will be no inflation momentum in Germany, and there is even a risk of a deflationary development.

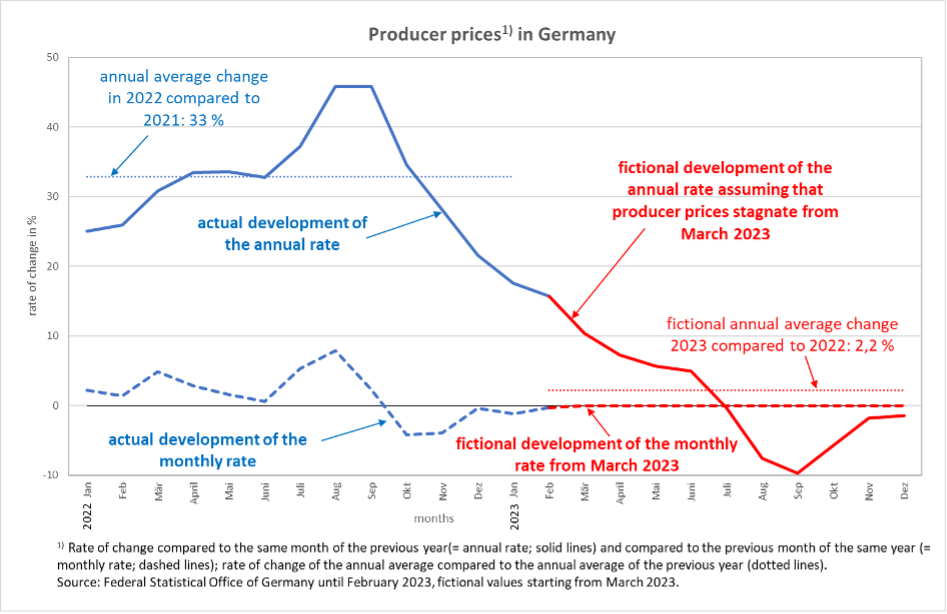

What is the situation in the EMU as a whole? We have made the same calculation for the monetary union of the now 20 states on the basis of producer price data from Eurostat, which, however, only extend to January 2023 (Figure 2). Accordingly, we assume stagnation in producer prices from February 2023.

Figure 2

The result of this fictional calculation is similar: the annual rates decline rapidly and move into negative territory from the summer onwards, although not as strongly as in the calculation for Germany. With some delay this will also be reflected in consumer prices across the EMU. As early as early summer, the ECB will only be able to justify with great difficulty why it is not immediately and rapidly lowering interest rates again, especially when relying on a data-based approach.

Wage policy in the EMU will also have to react to the new outlook for prices. After labour costs in the EMU rose somewhat more strongly in the fourth quarter of 2022 than in the previous quarters (by 5.7 per cent compared to the fourth quarter of 2021), it must also be recognised on the trade unions’ side that there is no longer an inflation dynamic this year that would justify wage deals far above the norm of about four per cent with the argument “real wage protection”.

What does the ECB want?

One must therefore ask again what the ECB means when it emphasises, as it did recently in the press release of 16 March, “the importance of a data-dependent approach to the Governing Council’s policy rate decisions.” For this press release also states that ” … underlying price pressures remain strong. Inflation excluding energy and food continued to increase in February.”

This alludes to the core rate, which in fact does include – as should be noted – energy and food prices, namely indirectly via the energy and food intermediate inputs. They influence a large proportion of the prices of those products which are used to calculate the core rate. Therefore this rate will also be dragged down. The declining commodity prices, which are already clearly visible in the producer price index for industry and for services, will thus feed through to the core rate. A “data based approach” should take this into account.

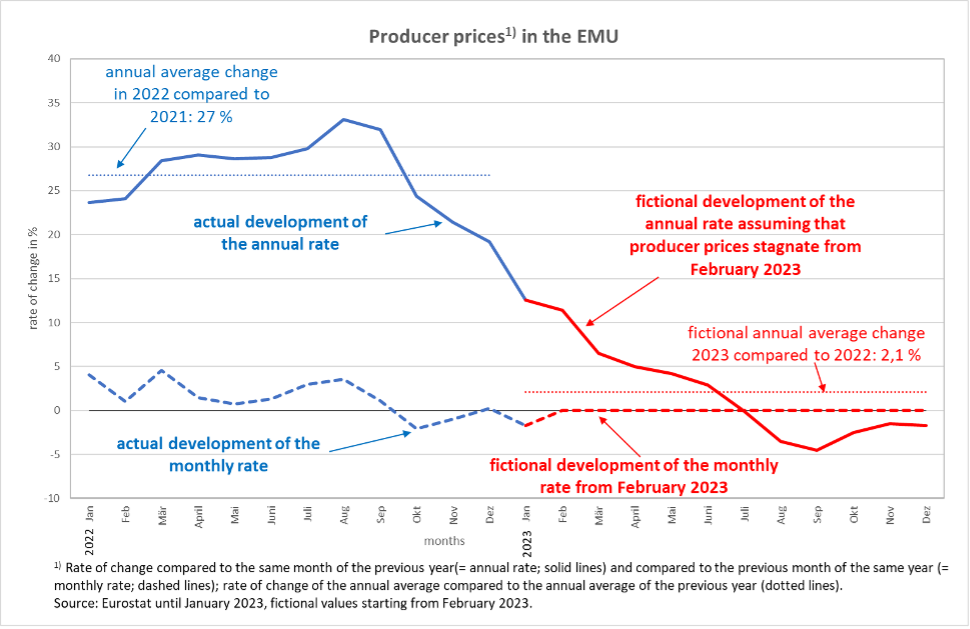

One has to bear in mind once again how extreme the current monetary policy of the ECB is. If one compares the ECB’s current interest rate policy with the three previous phases in which it raised key interest rates, it becomes clear that the current restrictive course goes far beyond the earlier phases (Figure 3).

Figure 3

This was justified by the ECB by the historically extreme price development. But the historically indeed special price surge is now followed by a historically equally impressive price decline, presumably leading into deflationary territory. Given the level of interest rates already reached, this new phase of price development endangers investment activity to an extent not seen before.

Aren’t real interest rates low?

The argument that, in view of the still high inflation rates (compared to the previous year), real interest rates – i.e. nominal interest rates minus the rate of price increases – are low and therefore not a real obstacle to investment, was wrong from the beginning because it did not take into account the inflation coming from outside. Now, however, it is obviously pointless. It completely ignores the timing behind investment decisions.

If an investor today is considering whether to take out a loan for a tangible investment project, he knows when he calculates what nominal interest rates he will have to pay when he signs the contract with the bank. But he does not know what prices he will be able to achieve in the future for the products he wants to bring to market with the help of the investment project. If he takes the development of the last few months as a yardstick, as we have shown in this paper, he must expect that the prices for his products will not rise again in the future either. This means that his real interest rate is clearly positive and far higher than the “real interest rate” calculated by many economists using the current inflation rate. This expected real interest rate must be borne by the expected profit rate of an investment project. So it is no wonder that investment activity in Europe is currently collapsing and the employment situation is deteriorating again. Monetary policy is achieving its goal, namely to reduce demand and investment via the transmission mechanism it expects – but its action makes no sense at all in view of the already existing trend towards normalisation in prices.