European monetary policy continues to puzzle. Although there is no longer any risk of inflation, the ECB is hesitant to recognise this and implement it in faster interest rate cuts. The inflation rate for the monetary union as a whole is a moderate 2.4 per cent, with slight movements up and down. But inflation rates are diverging significantly from country to country because wage developments in recent years have reacted very differently to the initial price shock. Nor is the development of prices between sectors of the European economy uniform. In industry, profits are under enormous pressure.

Even for Germany alone, the interpretation of the latest figures is not easy. As Eurostat reports, the (European harmonised) inflation rate for Germany was 2.8 per cent, which already makes a significant difference to the 2.4 per cent reported by German statistics. It is surprising that a German business newspaper reports that experts had expected a somewhat sharper decline in the inflation rate, namely to just 2.3 per cent. According to the Handelsblatt, this is likely to reinforce the scepticism of those central bankers who are critical of further interest rate cuts in quick succession. Unfortunately, we are not told why the central bankers do not view the 2.8 percent with much more scepticism.

Significant regional differences

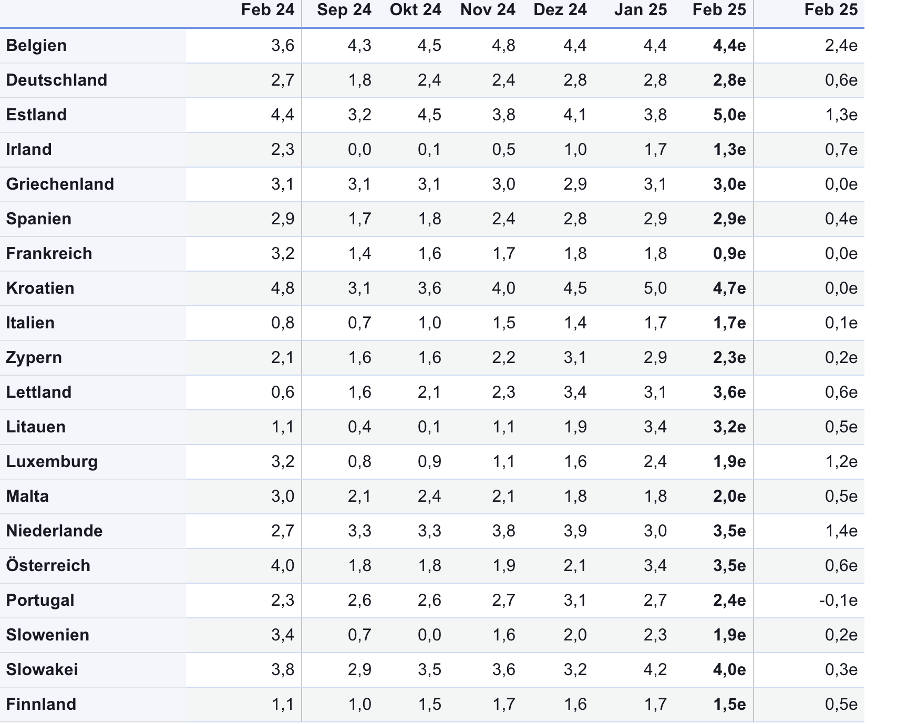

Even more surprising is the fact that in February the European heavyweight France had an inflation rate of only 0.9 percent. Italy is at 1.7, Finland at 1.5. It gets blatant in some smaller countries. Belgium recorded 4.4 per cent, Estonia 5.0, Croatia 4.7, Slovakia 4.0, Latvia 3.6 per cent, the Netherlands and Austria 3.5 per cent. The original Eurostat table (see link above) shows the current values in February 2025 compared to February 2024; the last column contains the monthly changes.

Table 1 Inflation Rates at Consumer Level

How can this be? How can inflation rates diverge so widely when monetary policy is the same? Even crazier: how can 2.4 or 2.3 for Germany be significant for the European central bankers, but the huge differences between the countries are not? Doesn’t the fact that monetary policy apparently has no influence on national rates show that the direct influence on the eurozone as a whole must also be very small, so that philosophising about 2.3 per cent, 2.4 per cent or 2.8 per cent in Germany is pointless from the outset?

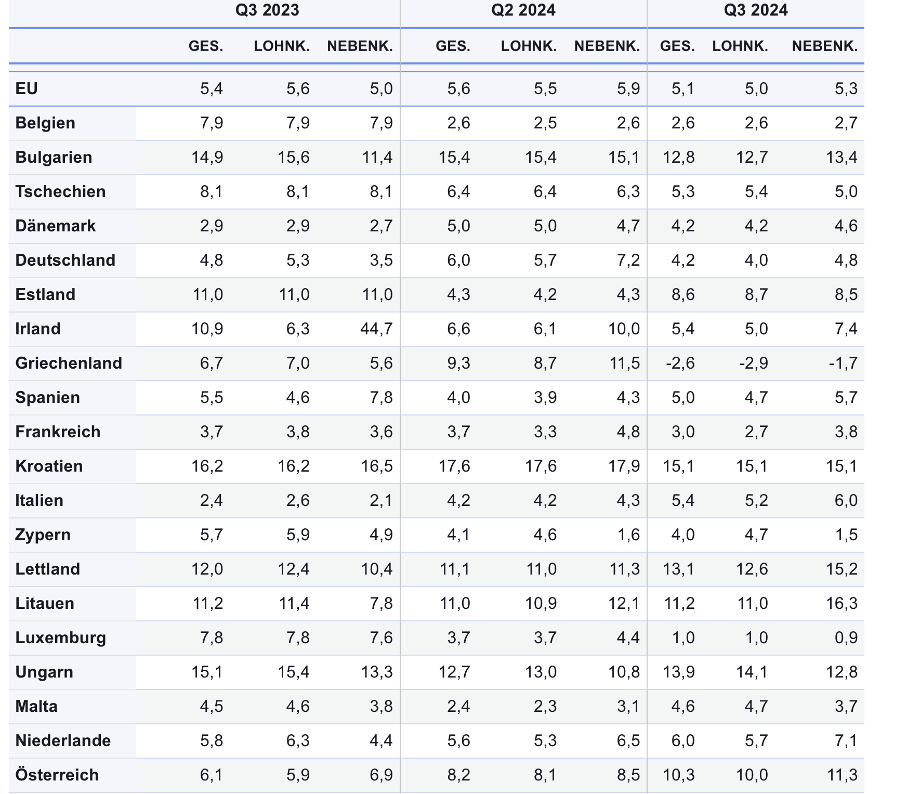

Another correlation is evident. Where wages have risen excessively in the last two years, consumer prices are now also rising more sharply, as shown in Table 2 from Eurostat. In Belgium, the rise in wages has now slowed, but in Estonia, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands and Austria, wages are rising much more sharply than would be justified by their productivity development.

Table 2 Labour Costs

(this is the excerpt from a Eurostat graph with quarterly values of total labour costs for the economy as a whole, as well as the breakdown into wages and non-wage costs, which can be found here)

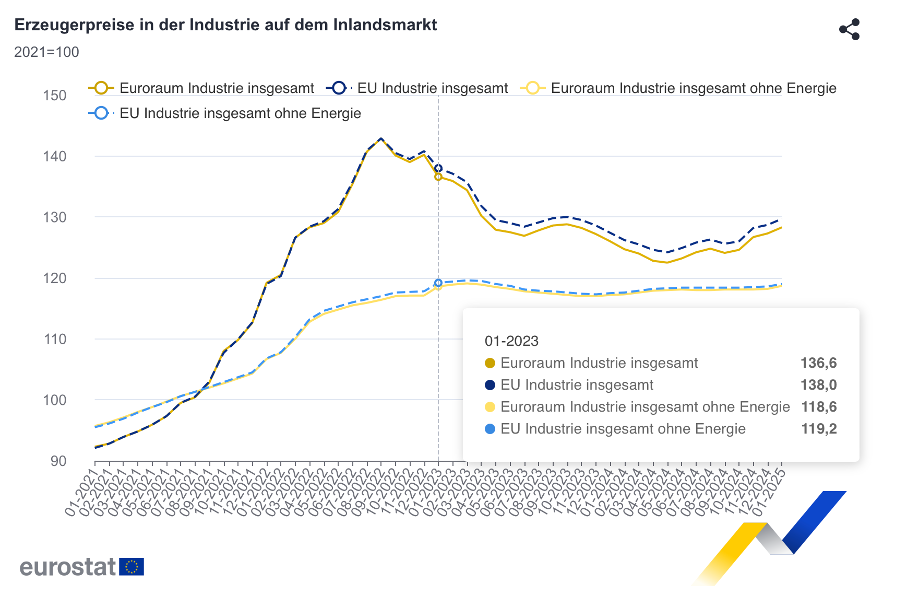

Even more remarkable is the discrepancy between (overall) consumer prices and producer prices in industry. As Eurostat reported midweek, producer prices excluding energy products rose only slightly in February 2025. However, they rose for the first time in a long time.

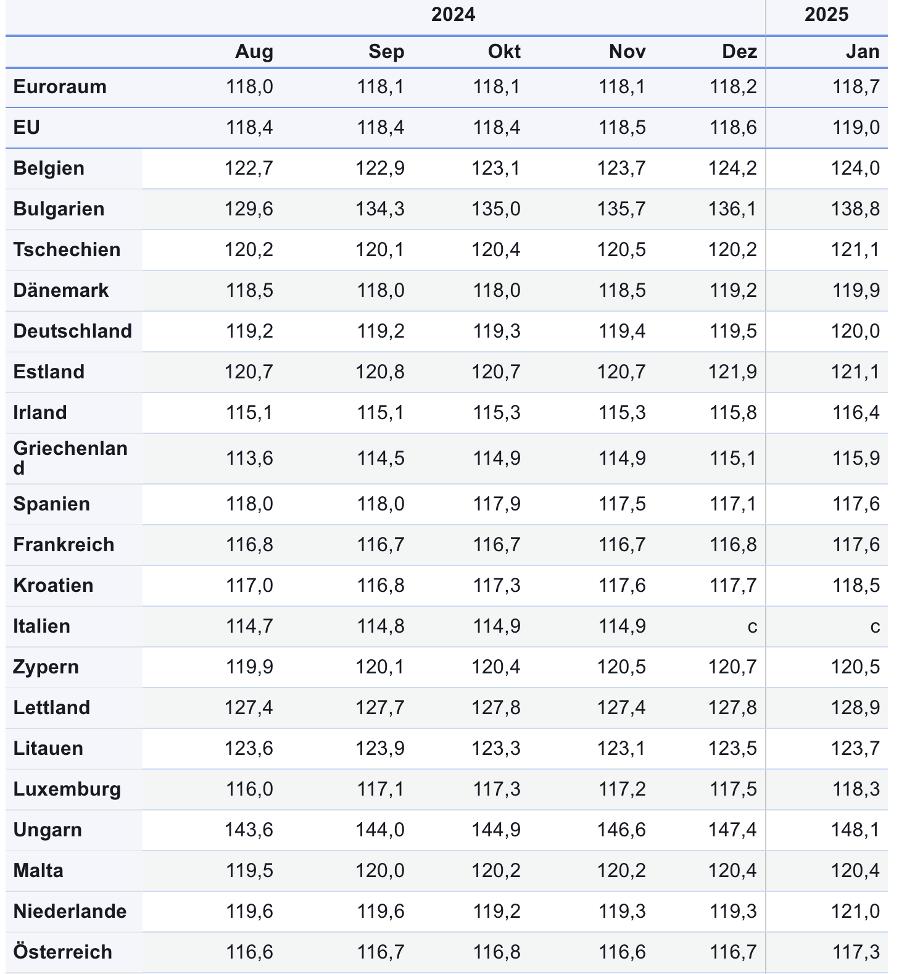

As can be seen in the original chart, the index was 118.6 in January 2023 and 118.7 in January 2025. This means that the price level at this level has been absolutely constant for over two years. As Table 3 shows with the national data for the same series, there has been no upward leeway for these prices in the past six months, even in the countries that have seen high wage cost increases and relatively high consumer price increases. This shows how strong competition is within Europe at this level.

For industrial companies in the EMU as a whole, absolutely stable prices with wage increases of around five per cent mean that competitive pressure is enormous and profits are shrinking. Since productivity gains are not to be expected with stagnating production, unit wage costs are also rising at a similar rate. Only in the service sectors can the cost increases be partially passed on in prices, which explains the still relatively high price increases for services.

Table 3 Producer Prices Industry

No risk of inflation

All in all, there is no sign of any inflationary danger for the euro area. Fluctuations in consumer price increases may go up or down, but that is not a problem. Monetary policy simply has no way of controlling the inflation rate to within a few tenths of a percentage point. Since wage costs are now under considerable pressure everywhere, there is clear relief from this side. In Germany, the latest wage increases have shrunk drastically compared to those of two to three years ago; at Volkswagen, wage cuts have even been agreed on balance. The wage agreement that has just been negotiated at the Post Office is also more than moderate at well under three per cent per year.

This will gradually spread to most other countries, as can already be seen in Belgium, for example. If competitive pressure in industry is so great that significant wage cost increases cannot be passed on over several years, the next step is for falling wage increases to lead to falling prices there. Then price increases in the economy as a whole, which are well below the inflation target of two per cent, are likely again. Whether this also applies to Eastern Europe, however, is an open question.

It is also apparent that the average data for the euro area, which the central bank usually uses, are not meaningful. The real interest rate for the average consumer in the EMU may currently be zero, but in France the real interest rate is much higher, and in some Eastern European countries it is clearly negative. For most companies in industry, the nominal interest rate is much too high because they cannot raise their prices and their production is stagnating. Even an interest rate of zero would not be an incentive for them to invest.

The ECB is wrong

In view of such data, it is more than surprising that there is apparently enormous confusion at the top of the ECB. Isabel Schnabel, for example, says that growing geopolitical fragmentation, climate change and labour scarcity pose measurable upside risks to inflation in the medium to long term. This is particularly true, she says, as the recent rise in inflation may have permanently affected (caused “scarring” of) consumers’ inflation expectations. This inflation increase has also lowered the barriers for companies to pass on adverse cost-push shocks to consumer prices.

That is economics from another world. There is no evidence that companies could now pass on costs more easily; the opposite is true, as shown above. The threat of inflation that is being painted here by force does not exist. There is also no justification for the more than general statement that geopolitical fragmentation, labour shortages and climate change pose ‘measurable’ risks to price stability.

The ECB should focus on the real danger that can be seen in the figures, namely that some countries, particularly in Eastern Europe, are deviating far from the wage path that is compatible with a two percent inflation target over the long term. Major conflicts are looming on this front, because the affected countries are losing competitiveness and their domestic industry is at risk of being completely wiped out.