Germany’s current voting system does not provide the best democratic outcome, explains Heiner Flassbeck.

Translated and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

A farce, says the German-language bible Duden, is a “matter in which the given intention, the given goal, is no longer to be taken seriously, and is only ridiculed and mocked.“ This is exactly what happened yesterday in the state parliament of Thuringia. The task given to parliaments by society to represent the will of the people was ridiculed by elected “representatives of the people”. A majority of the parliament ridiculed democracy by electing a person, Thomas Kemmerich, as prime minister whom nothing, absolutely nothing, except the farce played out by the conservative parties, entitles to occupy this role.

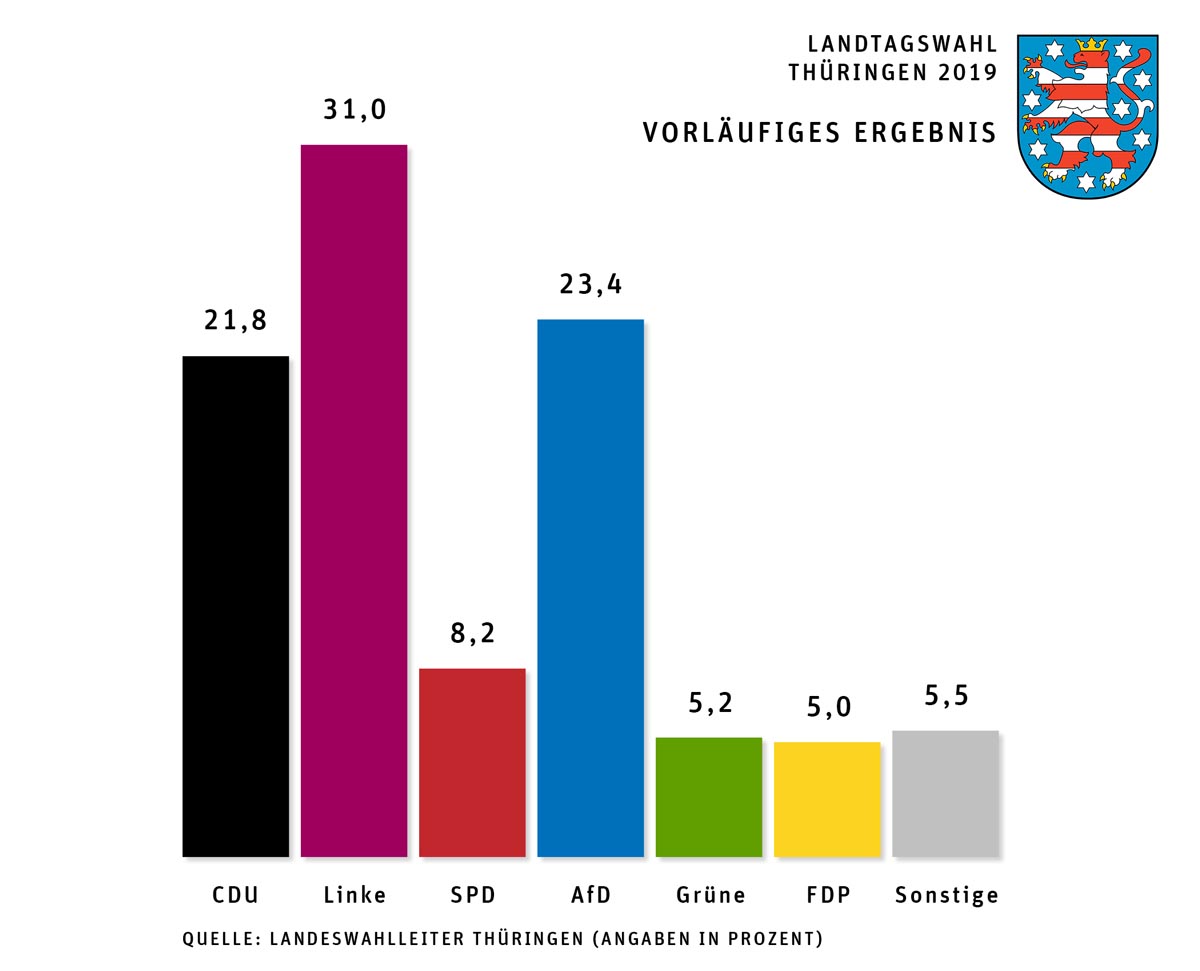

One can certainly argue whether it was a wise idea of the potential tripartite coalition of the Left, SPD and Greens to put their programme and their candidate for the post of prime minister up for election, after months of negotiations, in a parliament where the fronts are totally hardened and where they have no majority of their own. But when it happens that three democratic parties, with a programme that is very close to the middle of the political spectrum, propose to re-elect a politician as prime minister who, because of his moderate position, enjoys great recognition far into the conservative electorate, then it is a slap in the face for voters and for democracy. Why? Because those who have a majority, and have categorically ruled out any cooperation with the AfD since the election in October, decided to elect, together with the AfD, a man from the FDP as prime minister: a prime minister whose party only just managed to clear the five percent hurdle in the election and who has neither a programme to show for it nor could rally a comparable minority coalition behind him.

One certainly does not expect the AfD, co-led in Thuringia by Björn Höcke, to have any thoughts about democracy from the outset. Mr Höcke’s mockery of his own voters, which is expressed in the fact that the party puts forward its own candidate but unanimously chooses another, must be obvious to the voters of the AfD. It is scarcely credible that the CDU and FDP have involved themselves in such a puerile manouevre, which only serves as a showcase for “toothless democracy“. And the fact that national FDP chief Christian Lindner needed a whole day and fierce criticism from his own party to distance himself clearly shows that he fundamentally lacks the ability to make political decisions. The fact that the five-percent FDP man in Thuringia actually accepted this appointment shows how little many of our elected representatives know about democracy. Compared to the FDP’s initial total failure, the CDU party leadership, at least, quickly changed tack and declared the whole procedure unacceptable. However, it must now show that it is capable of putting its words into action.

The events in Thuringia, however, are due to deeper-seated problems in our exercise of democracy, which are hardly discussed even now. In politics, factual discussions are increasingly being replaced by discussions about personalities or parties. At the beginning of West German democracy, at least an attempt was made to discuss urgent matters. Today there are ritualised political debates by political professionals who know nothing about the matter, but who know exactly who their political opponent is. The coalition program (to be found here in German) that the minority government in Thuringia negotiated has not been discussed so far, but only the fact that the prime minister should come from the strongest party, which is die Linke (the Left Party). Anyone who looks at the programme and realises that the three or four members of parliament from the FDP and CDU are not to be found, who would have to give their indirect blessing to this, by abstaining in the election of the prime minister, knows that the political debate in Germany has descended far below the belt and is directly endangering democracy.

But there is no way around Germany thinking intensively about its electoral system. Immediately after the elections in Thuringia in October, I spoke (here) about ungovernability and its dangers, and that is exactly what has now been confirmed. With five, six or more parties in the parliament, there are no longer any easy constellations for forming a government; factual debate recedes into the background and tactics dominate, even to the point of puerile plots. I had written at the time and I hereby put it up for discussion again:

“Anyone who speaks in favour of multicolour coalitions with their tendency to smooth out all differences must be aware that in this way the party landscape is becoming increasingly frayed, because there is no one left whom citizens can really blame for the successes and, above all, the failures. This is what drives one to keep choosing new parties, because in case of doubt they convincingly – as the AfD is now doing – declare all the existing parties (the “old parties” in AfD jargon) responsible for all the misery.

No, the permanent five-party compromise is not the solution. Democracy lives from debate and confrontation. But democracies also need governments that are capable of acting and that can and want to change things. This is only possible if blocks can form that stand against each other and can take over from each other. If the formation of blocks can no longer be achieved through antagonism in terms of content (“freedom or socialism”), the formal antagonism must take the form of a brutal majority vote. Whether this is done through the direct election of an extremely powerful president like in the United States, or through a two-tier system as in France, where in the end even a party that could only win a quarter of the voters can gain almost absolute power.

Perhaps there are much better solutions, but that is unlikely. In Germany, therefore, we should begin to rethink and fundamentally question our own electoral system. This will be difficult, because almost everyone in Germany always believes that they have found the philosopher’s stone. In any case, it would be better to start rethinking soon, because ungovernability can become damned expensive in the long run.”