In a guest article for the FAZ, the German finance minister, Christian Lindner, has claimed that “European fiscal rules are the anchor of stability of our Economic and Monetary Union,” and stressed: “They are also not a matter of variable negotiation and interpretation” (our translation). This is a clear message to the EU Commission, which presented a proposal to reform the European Growth and Stability Pact in November 2022. When reading how the minister justifies his position, one has to be highly alarmed:

“High levels of debt and the associated costs worry me in view of rising interest rates. If a member state permanently breaks the rules, this will have negative consequences for all member states. The last debt crisis was just a decade ago. It showed that hard cuts become necessary once the trustworthiness of the state finances called into question.“

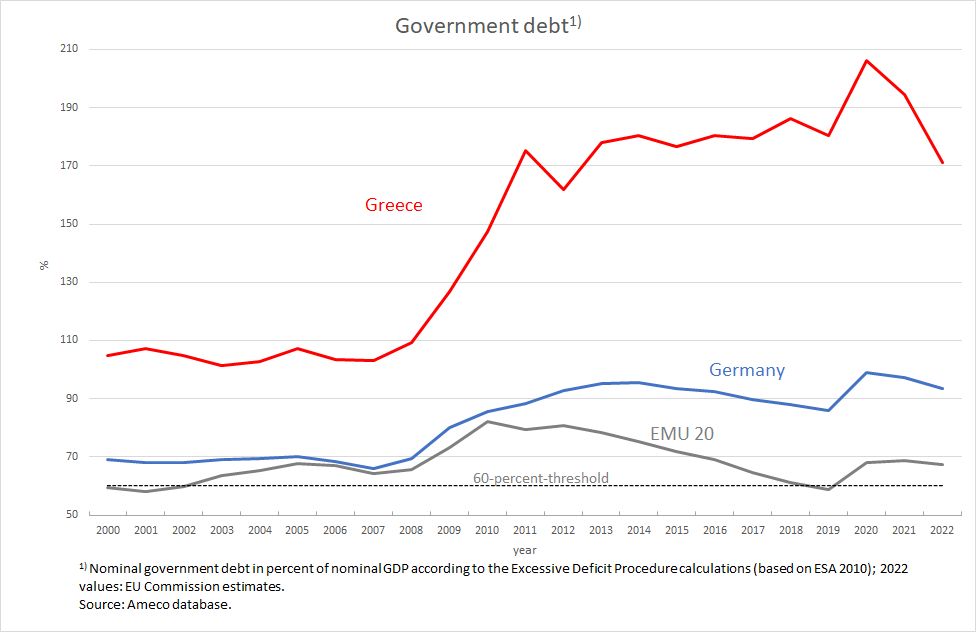

With the “hard cuts” in the event of a “debt crisis”, Christian Lindner is obviously referring to the example of Greece. However, data from the European Commission (Figure 1) show that these cuts have not had the intended success, namely a noticeably reduction in Greece’s national debt.

Figure 1

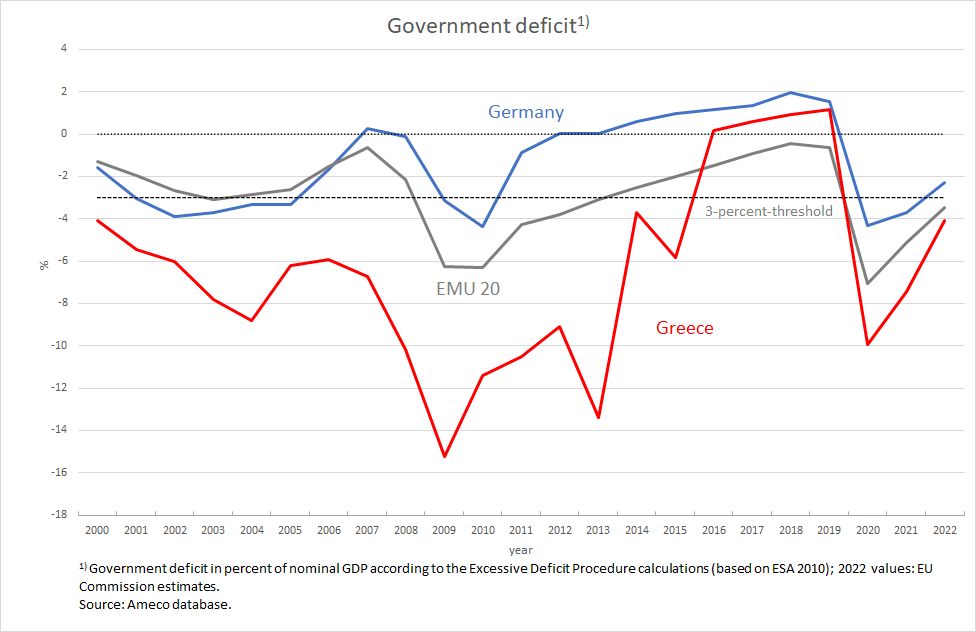

The opposite has happened: Government debt today is now at about the same level as in 2013, even though the Greek state has since reduced its deficits sharply and even generated slight primary surpluses for four years in a row between 2016 and 2019 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

The Greek state was able to do this despite a corporate sector running surpluses because households borrowed to an almost unimaginable extent year after year. However, overall government debt continued to rise over all these years. During the Corona crisis, the slump in the tourism business set the economy back more than elsewhere and caused the government deficit to grow accordingly. The debt level in 2022 is over 170 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP), still by far the highest in the EMU and the highest among the industrialised countries after Japan.

But instead of questioning the instruments used ten years ago to reduce public debt and precisely analysing their obvious failure, Christian Lindner makes things easy for himself:

“In member states with high debt ratios, the rules must lead to a noticeable reduction in debt quickly, credibly and sustainably. The reference values of three percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for the deficit and 60 percent of GDP for the debt level are not up for negotiation. However, as clear as these limits are, their enforcement must finally become just as clear. It is no use having rules that are subject to political whim and never work in the end.”

The German finance minister thus explains the lack of enforcement of the fiscal rules as the cause of their non-observance – a conclusion that is either banal because it is tautological or proves that he really believes that the path taken at the time to reduce debt was just not pursued vigorously enough to produce visible success.

Has he really forgotten the extent of the cuts that were actually made, which the European Commission and the European Central Bank demanded from the Greek population, especially at the instigation of the German finance minister at the time, Wolfgang Schäuble? And precisely with the declared aim of putting the state finances back in order and restoring the population’s confidence in them?

If this dose of “medicine” actually worsened the state finances at the time, as evidenced by the government debt ratio, and has not helped in the promised sense to this day, how could more of it have worked in the desired direction? Where is the recovery that the supposed stability anchor of the monetary union called European fiscal rules should have brought? Or does this anchor only help some members to achieve stability, while for the others it turns out to be a millstone around their necks that repeatedly brings them to the brink of capsizing? But what is the state of the common currency boat EMU and the common economic boat EU, whose seaworthiness needs to be restored?

After the “hard cuts” Greece is a broken country

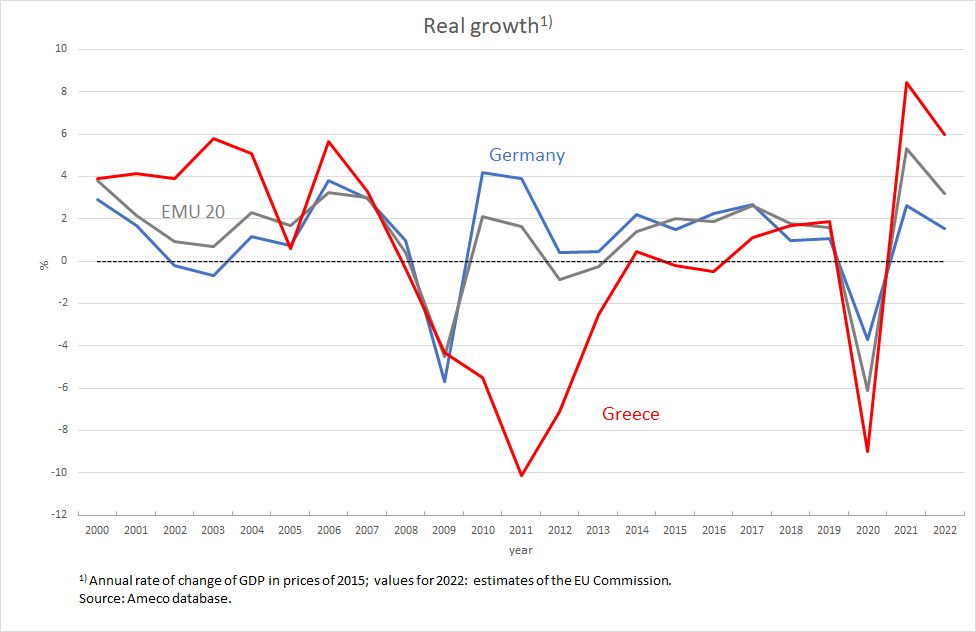

Unfortunately, the Greek reality looks very bleak. Greece has hardly been able to generate any growth until 2013 after the incredible slump in the aftermath of the 2011 crisis (Figure 3).

Figure 3

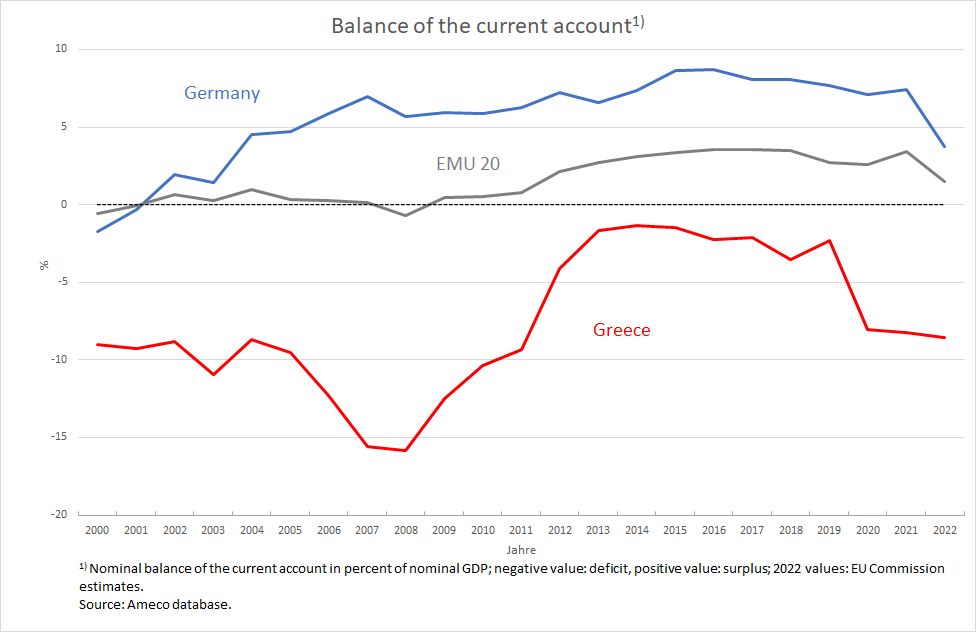

The current account deficit, which had fallen sharply in the wake of the economic collapse, has been back above 8 per cent of GDP for three years (Figure 4).

Figure 4

This is, as mentioned above, mainly a consequence of the Corona shock that hit the Greek tourism sector in 2020, which accounts for a significant share of the country’s economic output, namely exports. Imports also collapsed in 2020, but nowhere near as much as exports, which in sum significantly worsened net exports and thus the balance of the current account. After a recovery in the travel sector in 2021 and 2022 – the positive balance of the services account now even exceeds its 2019 level – the energy crisis is clearly making itself felt: Nominal imports have increased much more than nominal exports.

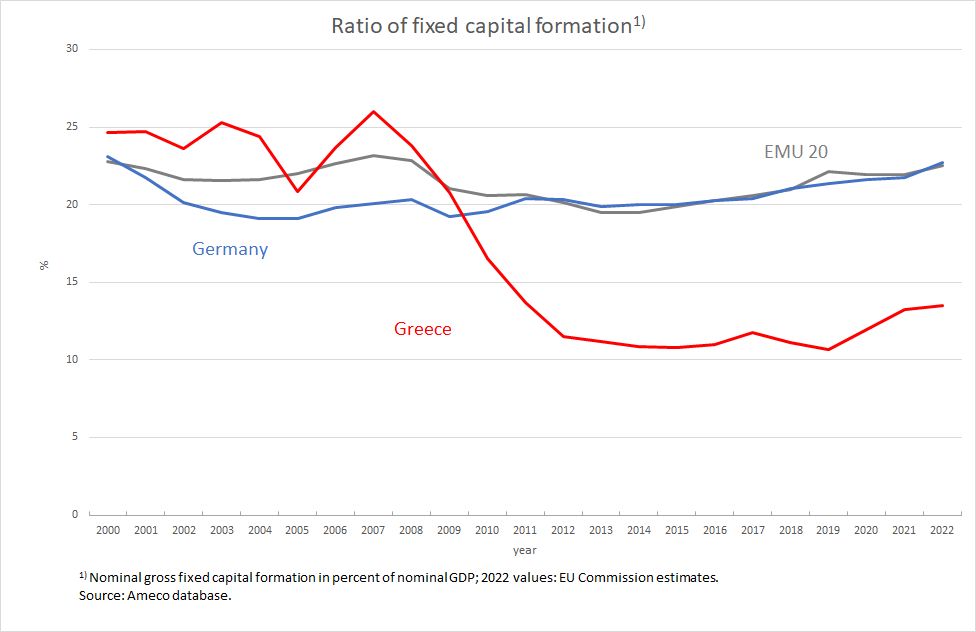

Greece’s investment ratio has flatly halved as a result of the euro crisis and is at the lowest level of all European countries (Figure 5). A crisis-fighting policy cannot fail any worse.

Figure 5

The fundamental importance of fiscal balances

The fact that the net financial assets of all economies together are always zero provides the key to a clear analysis that, thanks to its pure logic, is independent of economic schools of thought. Everything that is currently being discussed on the subject of government debt and fiscal rules tacitly assumes that in all countries there are precisely the conditions on the corporate side that ensure that all other sectors are not forced to accept revenue deficits, i.e. debt. But such conditions have not existed for a long time, as will be shown empirically below.

How does debt arise? Debt always arises when there is a gap between expenditure and revenue in the accounts of an economic unit. Behind this is a real imbalance of the kind that one party lives above its means (i.e. uses more real resources than it puts into circulation) and the other lives below its means. Internationally these gaps between revenue and expenditure do not cause harm if there are conditions within an economy that ensure that one group’s living below one’s means is systematically offset by another group’s living above their means.

Typically, it is the private households in an economy that spend less than they earn because they try to provide for the future by saving. The financial balance of the private household sector is therefore regularly positive: there is always a surplus. And typically in the past it was the companies that spent more than they earned, i.e. they had a negative financial balance, i.e. a deficit. They invested in the hope of making future profits that would at least be sufficient to pay the interest that usually had to be paid on a loan.

The corporate sector no longer borrows

The state does not actually have to incur debt as long as it is ensured that the corporate sector invests at least as much as is saved elsewhere, i.e. that it fills the output gap of private households precisely through its own investment demand with correspondingly high own debt. Then economic development does not collapse, but at least stagnates.

But this is by no means guaranteed. The financing surplus of private households causes a financing deficit of companies. This is because the income of private households comes from companies in the form of labour income (and from the state in the form of labour income and transfer income). It is by no means self-evident that companies simply accept their revenue deficit and do not try to react to it by reducing their expenditure.

And an economy in which companies compensate for the savings efforts of private households by accepting their own deficits is still a long way from a development that could be described as “growth” or “positive change”. Growth, after all, requires that companies not only offset the surpluses of private households with their own deficits, but that they do even more than that, namely accumulate additional deficits in the form of debt-financed investment demand. The corporate sector must therefore incur more debt overall than corresponds to the surpluses planned by private households.

Consequently, if the government wants to ensure positive economic development, it must either create conditions that induce the corporate sector to fully fill this debtor role or it must itself aim for expenditure surpluses, i.e. incur debt.

Foreign countries consist of the same sectors as domestic countries. They are in no way suited to being a long-term debtor on balance to take on the role of a stopgap for the gap that the domestic sectors’ willingness to save tears in a country’s overall demand. It is a matter of logic and a change of perspective to realise that foreign countries have to solve the same problem of the saving behaviour of their private individuals as the domestic sector.

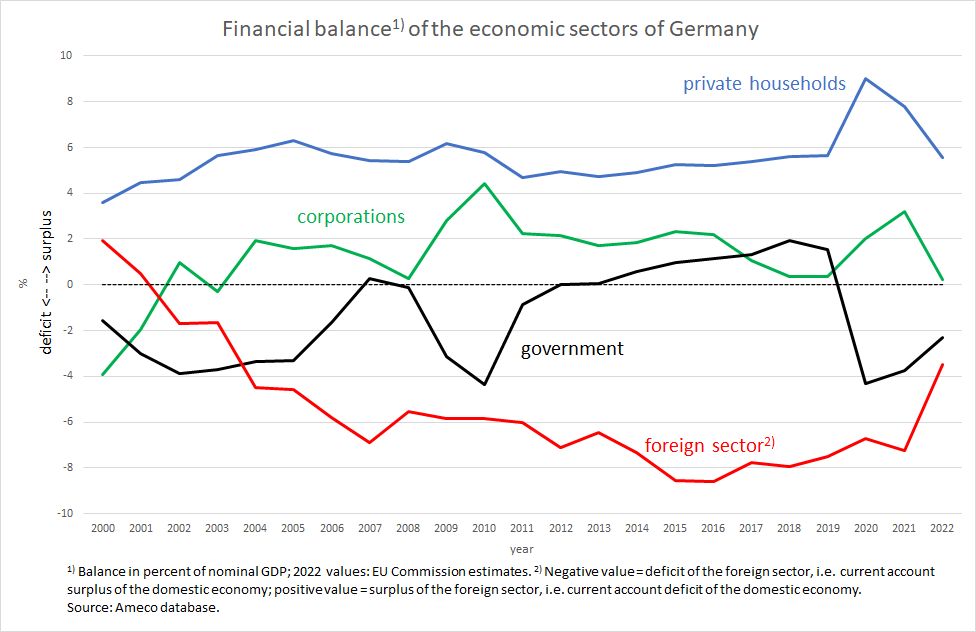

Germany is no role model

Empirical evidence exposes the problem of European fiscal rules. The private household sector in Germany is traditionally fond of saving: around six percent of GDP is usually put aside (Figure 6). Unlike in previous decades, German companies have not taken on the counterpart for 20 years. Despite massive tax cuts in the early 2000s, the corporate sector has no longer contributed to closing the gap between income and expenditure, but has widened this gap through its own savings in almost all years – the green line in Figure 6 is above zero. This has permanently weighed on the economic development of the national economy and has long been lamented under the keyword “investment weakness”.

Figure 6

Parallel to the private sector’s urge to save, the public sector has endeavoured to reduce its deficits or even to generate surpluses. Only in response to obviously severe crises such as the 2009 financial crisis or the 2020/2021 Corona crisis did the public sector allow greater indebtedness. Had it not done so, both times the crash of the economy would have been much bigger than it already was. This is because the companies reacted to the crises in each case with a strong expansion of their savings activities.

The fact that the German economy did not permanently decline under the years of austerity in all three domestic sectors is solely due to the annual foreign debt, which rose to well over six percent of GDP: debt-based surplus demand from abroad closed the domestic demand gaps. Germany bailed itself out of the austerity problem through mercantilism. The key used for this, as we have explained and empirically proven many times, was undercutting international competition through macroeconomic wage restraint in the monetary union.

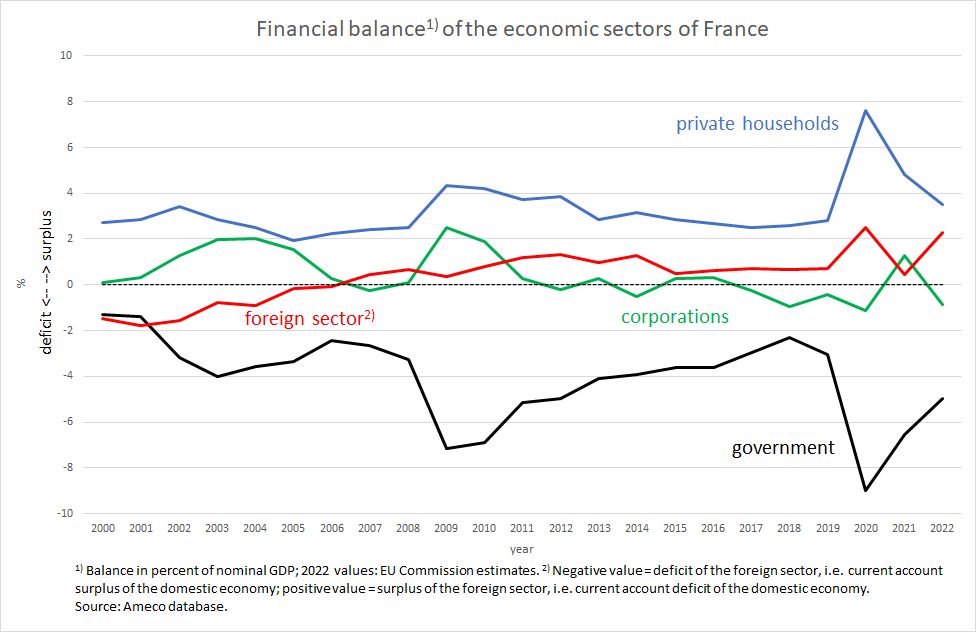

This has been felt abroad. France has been running a current account deficit – albeit a comparatively small one – for 1 ½ decades: the red line in Figure 7 is above zero, i.e. foreign countries – from France’s point of view – are running surpluses with France. The French private household sector saves, albeit to a somewhat lesser extent than its German counterpart. The corporate sector is only borrowing very slightly, if at all. So the French public sector had no choice but to go into debt if the country wanted to avoid a permanent contraction of its economic output.

Figure 7

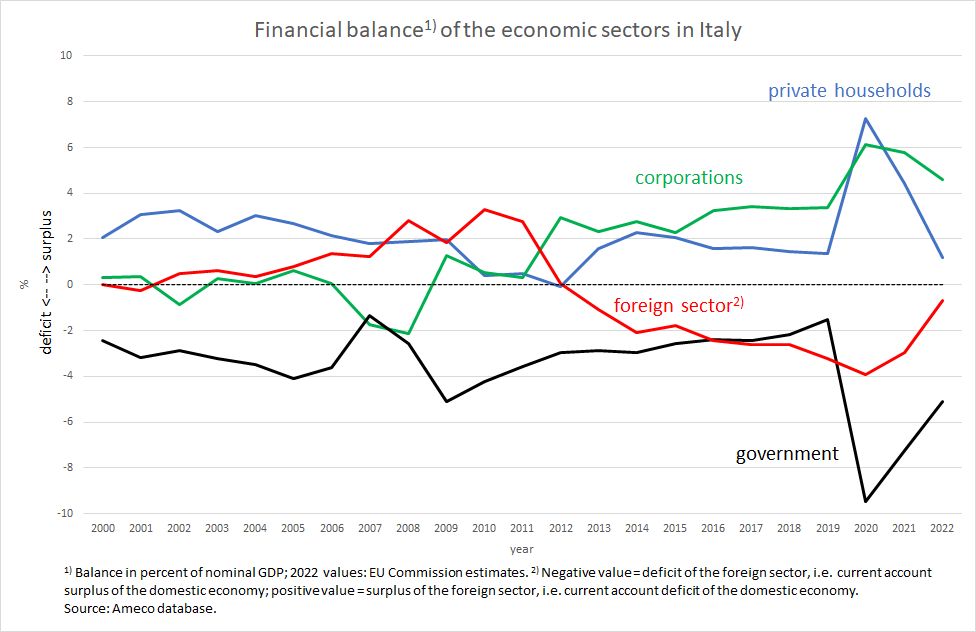

In Italy the problem of the saving corporate sector is much more pronounced than in France and, for the last ten years, even more serious than in Germany. If households in Italy were as keen savers as those in Germany, the domestic savings problem would be even greater. Since the peak of the euro crisis, however, Italy has succeeded in pushing – from its point of view – foreign countries at least a little bit into the debtor role by drastically reducing its imports of goods. Nevertheless, the Italian state also had to remain in the debtor role if it wanted to avoid a permanent recession, which private savings would otherwise have inevitably brought with it.

Figure 8

The logic of the financial balances is absolutely compelling

These three examples show that one cannot meaningfully analyse a country’s public debt without looking at the saving or debt behaviour of the other three sectors. Those who criticise the debts of the public sector and want to see them reduced must explain who should do the borrowing instead and under what circumstances. For it is undeniable that on the one hand there is always a certain willingness to save on the part of private individuals, which is even more pronounced in times of crisis than in “normal” times. But on the other hand, it is also obvious that every country strives not to fall into a recession or even to remain in one permanently, as is pre-programmed by the savings behaviour of private individuals.

If, in parallel to this private savings drive, each country strives not to incur new public debt or even to reduce old public debt, each country is dependent on other countries, the “foreign countries”, borrowing from it. (Which domestic sector of these other countries takes on the excess spending is irrelevant). Logically, this cannot work: If no one wants to be a debtor, but everyone wants to be a saver, the economy shrinks in all countries. There can be no economic development without debt.

The interdependence of the sector balances of different countries is even more pronounced within a monetary union because there are no exchange rates whose change can bring about a change of role between debtor and saver, between current account deficit country and current account surplus country. Therefore, especially in a monetary union, it is imperative to always discuss government deficits and debt in connection with the balance of the foreign sector and foreign debts or assets.

The European fiscal rules were set up without taking this logic into account, and compliance with them therefore fails on an ongoing basis. Anyone who recognises the causes of permanent foreign deficits of some countries and permanent foreign surpluses of others and willing to eliminate them has found the real anchor of stability of a monetary union. The sustainability of public debt then follows automatically.

When will the euro crisis be mastered intellectually?

We have already become accustomed to politicians not understanding crucial connections in the area for which they are responsible. But politicians who are not in a position to learn from serious mistakes once they have been made are yet another category. Those who, even after ten years, are not prepared to take note of the consequences of the unspeakable decisions made by the European finance ministers (together with the central bank and the EU Commission) during the euro crisis are certainly causing enormous damage throughout Europe.

There is a lot of talk these days about coming to terms with the political mistakes during the pandemic. The overcoming and coming to terms with the mistakes during the so-called euro crisis, on the other hand, are apparently not worth talking about, although we could see the consequences every day if we only wanted to. The fact that the EU Commission has done nothing to avoid similar mistakes once and for all is falling on its own feet now that the next crisis of the Union is beginning to emerge. The Commission’s reform proposal gives rise to fears that the approach will be just as naïve this time as it was last time.

A decisive role will again be played by the “frugal” countries, i.e. those with unjustifiably high current account surpluses, such as the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark in addition to Germany, and other countries that want to insist on the “hard” fiscal line for ideological reasons. It is no coincidence that Christian Lindner just visited his Finnish counterpart. The EU Commission is technically unable and politically not courageous enough to put the countries in their place precisely because of their surpluses, which clearly violate European rules.

One only has to study the press release on the Commission’s reform proposal to see the imbalance between fighting sovereign debt and fighting trade imbalances. While considerable space is devoted to describing which adjustment paths for debt reduction should be established, underpinned, endorsed, reviewed and sanctioned in the future and how, the press release on the macroeconomic imbalances procedure merely states:

“The reform proposals for this procedure rely on an enhanced dialogue between the Commission and the Member States in order to reach a better common understanding of the existing challenges and the necessary countermeasures. … The assessment of whether imbalances exist would be made more forward-looking so that emerging imbalances can be identified and addressed at an early stage.“

First of all, it sounds as if, ten years after the euro crisis, we are still at the very beginning of a sound analysis beyond tautological statements like those of the German Finance Minister, because there is apparently a lack of common understanding of the problems – a frightening idea. Keywords such as current account and trade balances, inflation and unit labour cost differentials would have to appear in the Commission’s paper to even give the impression of seriously addressing the causes of the euro crisis then and the prevention of a new one.

And secondly, the wording comes across as if it is only about future imbalances and not about past and present ones. This is remarkable. After all, an accumulation of all current account surpluses and deficits over decades would actually be the counterpart of public debt, the sustainability of which is so worried about. Why shouldn’t the sustainability of foreign debt be viewed just as critically as that of government debt? Perhaps because it would then also be a question of the assets that economic subjects of the surplus countries have accumulated in other countries and which would then have to be critically scrutinised?

To start negotiations on the reform of the European fiscal rules from the German side under the general heading “The previous principles were and are correct, they just need to be followed more strictly” means not being interested in a real analysis and therefore also in a real solution. The fact that the FDP wants to distinguish itself in the face of lost state elections is not a good reason to sacrifice the logic that is fundamental for Europe’s positive development on the altar of party-political populism.

The countries affected by Christian Lindner’s blocking attitude, above all France, must defend themselves against this narrow-mindedness. This is not about diplomacy, but about confrontation. If the responsible politicians in Germany refuse to recognise even compelling connections such as the one between the financial balances of the national economies, nothing more can be achieved solely by diplomatic means.

The governments of the countries that understand the balance logic must go to the European public to explain their position and make it clear why no progress can be made with Germany. France, together with Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece, could form a critical mass that cannot be ignored, not even by the EU Commission, which would then be forced to take a stand. Whether such a critical mass can be achieved, however, remains to be seen.