Sometimes 13 does bring bad luck. At any rate, for Robert Habeck, Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, Chart 13 in the Federal Government’s Annual Economic Report for 2022, which he has just presented to the press, is not a stroke of luck, to say the least. It shows that the BMWK, as he calls himself, is making the climate his big issue, but is unmistakably walking on the shaky wooden paths of his predecessors when it comes to the economy. What the BMWK does not (yet) understand: Those who cannot master the economy will also fail in climate protection.

A government that has set itself the motto “dare to progress” needs investments. Anyone who not only wants to bring the economy out of the trough, but also fundamentally restructure it over decades, needs a great deal of investment. And because the FDP is on board, private investment is needed, because there is not too much money available for public investment according to the Liberals’ reading. But, as all informed people know, private investment has been the Achilles’ heel not only of the German economy, but of the entire European economy for many years.

Private investment is desirable, but where should it come from?

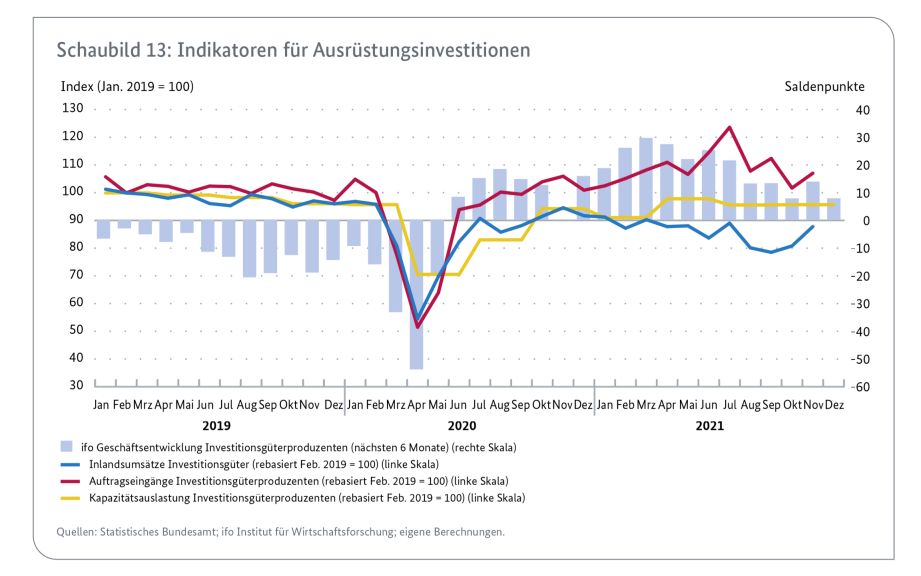

If you don’t have an upswing in private investment, but need it politically, then you’ll just make one up, the officials in the ministries involved in drawing up the report in Berlin must have thought. So they gather up everything they can find and put it in a chart that at first glance looks positive (see Figure 1): First, three of the four indicators show that private investment stagnated before the Corona shock, and the fourth indicator, the ifo survey-based sentiment indicator on the business development of capital goods producers, has been going downhill more or less continuously for over a year.

Figure 1 (original from JWB 2022)

After the Corona shock in spring 2020, the assessment of business development among capital goods producers (the blue bars) does go up – but where else should it go after such a shock? From the mere reaction to the deep slump it does not automatically follow that something has fundamentally changed in the industry’s obvious misery after the crisis. After all, the positive balances of the sentiment indicator are already becoming much smaller again. The real state of affairs can be seen in the domestic sales of the capital goods industry (the blue curve), which have resumed their downward trend from before Corona and, despite the upward spike in November, are more than ten percentage points below their value at the beginning of 2019.

So far so good or so bad. But the red curve seems to stand out positively from the blue one: it has risen significantly since the slump in spring 2020 until summer 2021. This is the incoming orders of capital goods producers, i.e. an indicator that reflects investment demand. However, unlike sales, this is the total demand for capital goods by German manufacturers, i.e. it also includes demand from abroad. But what does foreign demand for German capital goods say about the domestic propensity to invest, which is what we are talking about here? Foreign investment demand undoubtedly supports the German economy, but it does not lead to an increase or restructuring of the domestic capital stock, which the BMWK considers so necessary.

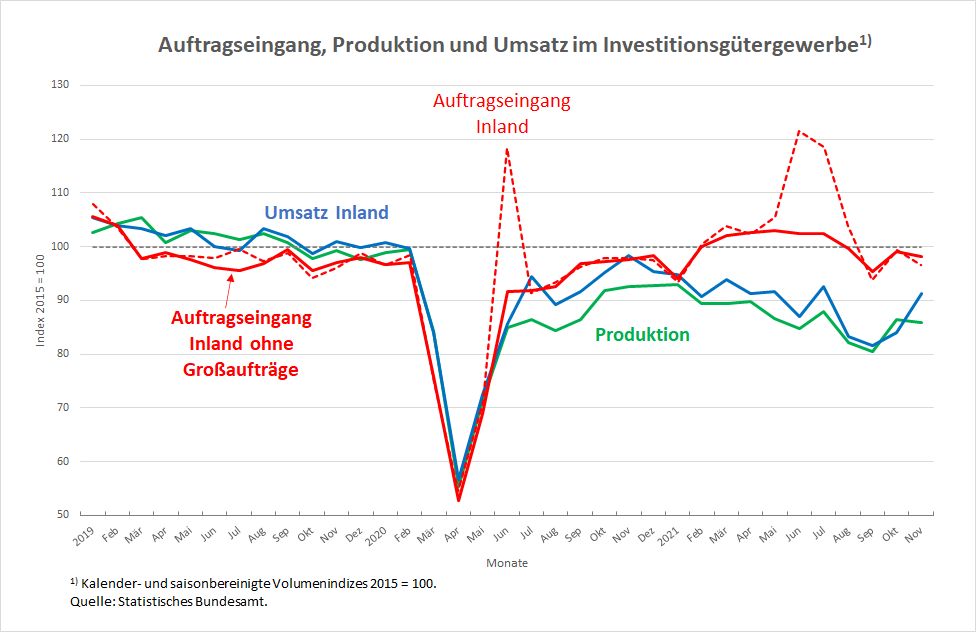

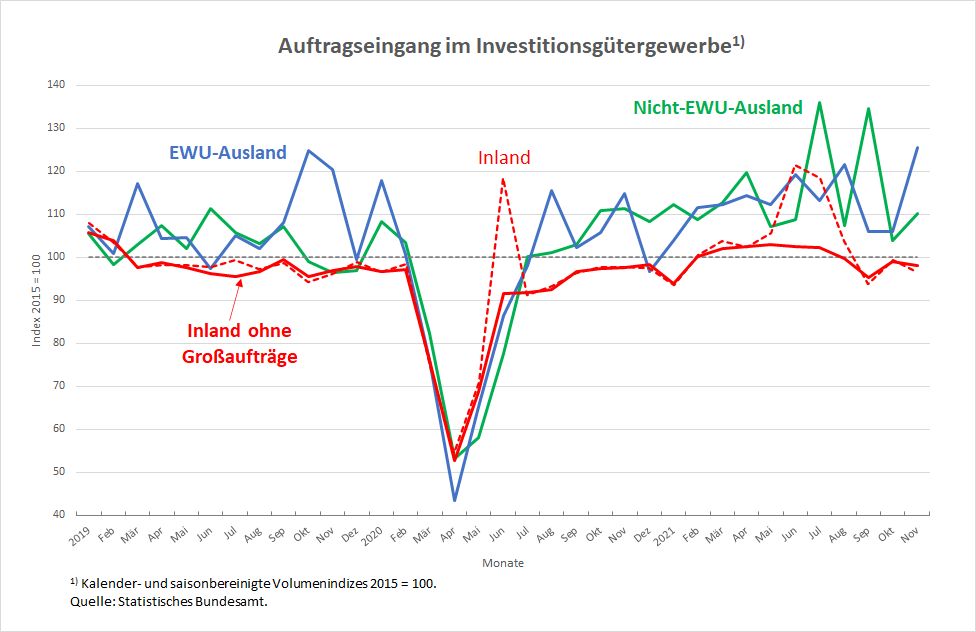

Anyone involved in business cycle analysis knows that a reliable indicator of domestic investment activity is domestic demand among domestic manufacturers of capital goods. Using this indicator, the picture looks like this:

Figure 2

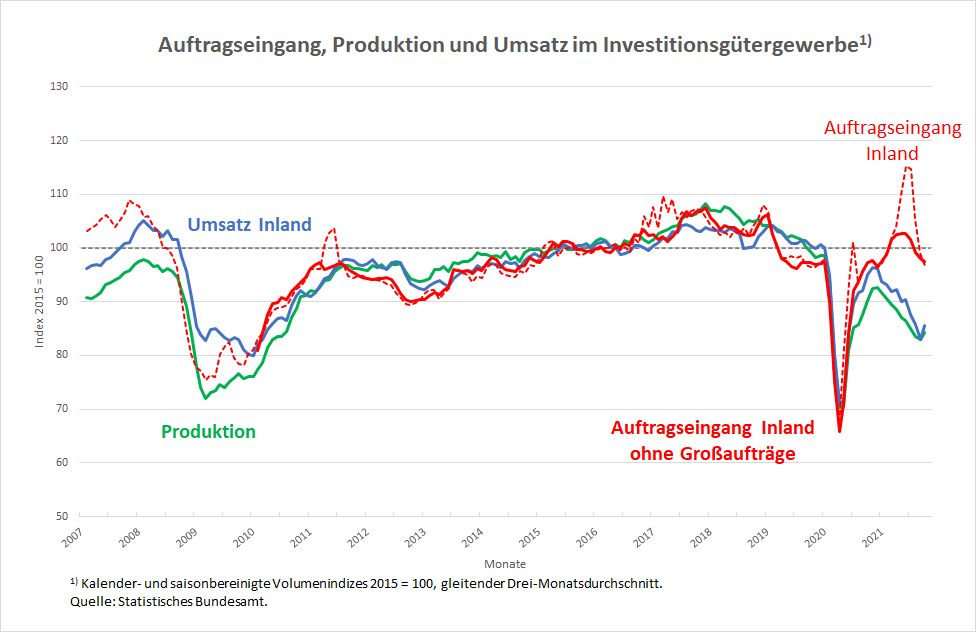

Neither domestic demand nor domestic turnover and production at German capital goods manufacturers suggest that things are looking up in any way. If we take domestic new orders excluding large orders as an indicator (the solid red line in Figure 2), there is virtually nothing left of the “all-time high at mid-2021” mentioned in the Annual Economic Report in paragraph 287. Instead, there is every indication that the glaring weakness in investment, which has been observed in Germany since the euro crisis in 2012 despite zero interest rates (cf. Figure 3), will continue after Corona.

Figure 3

Why should it be any different? The Corona shock was a major burden for companies, and nothing has changed for the better in all the other factors that are decisive for investment activity.

If anything is doing at least a little better, it is most likely investment activity in other countries (see Figure 4). At least foreign demand for German capital goods, namely that of non-EMU countries, has recovered much more strongly from the Corona shock than domestic demand. As said above, this is initially helpful for the German economy. But it cannot be in Germany’s long-term interest if its domestic capital stock does not keep pace with productivity developments elsewhere.

Figure 4

Even the so-called traffic lights coalition needs mercantilism

If you want to change and advance things in Germany, you have to deal with the domestic investment weakness instead of glossing it over. Obviously, the great German transformation at the beginning of this century was far less successful than almost all parties in Germany (including the three Ampel parties) would have us believe. The change of course pushed by the state (initially by the Red-Green coalition) and finally enforced, towards an improvement in competitiveness through “wage restraint” and the massive relief of companies from taxes and duties has not had the hoped-for effects.

Since then, Germany has regularly achieved high current account surpluses and has maintained its global market shares relatively well (at the expense of its trading partners in Europe and elsewhere), despite the fact that China and other developing countries are pushing their way into the world markets. But overall, this has not been enough to stimulate investment in this country. If you lower wages, you also lower domestic demand. If, in a monetary union, wages in the largest country are not raised in line with the central bank’s inflation target (plus national productivity) under political pressure, this not only depresses domestic demand, but sooner or later that of the entire monetary union, because all member countries are forced to follow the largest country and also exert pressure on their respective wages.

This is the core of the European malaise, and Germany is both its cause and its victim. Only if Germany abandons its attempt to gain and maintain competitiveness at the national level can Europe overcome its internal market and investment weakness. Only then will Europe have a chance of winning majorities for a policy that does justice to the protection of nature and the climate despite the enormous frictions this entails.

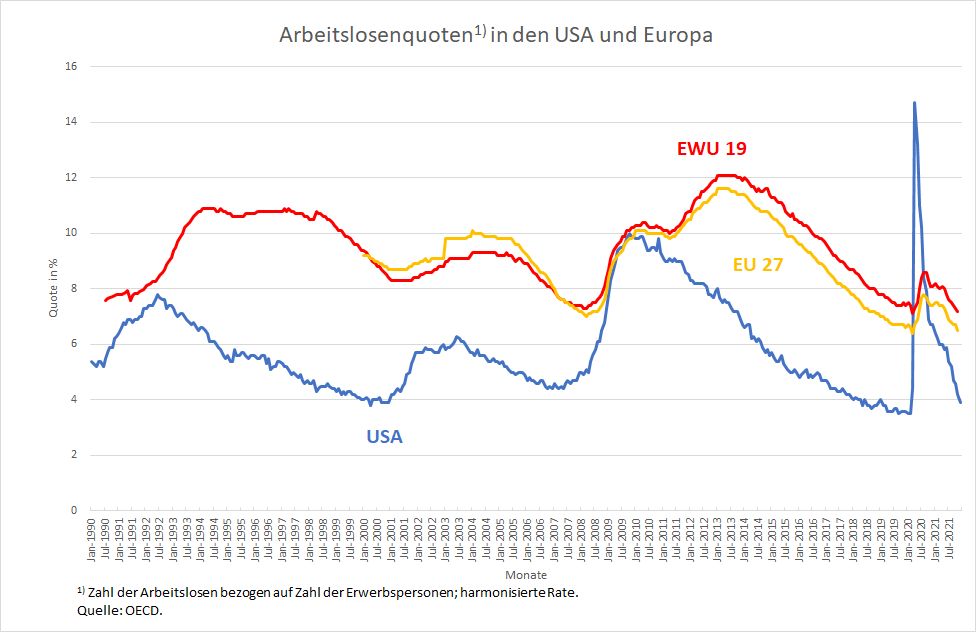

Europe’s plight is best illustrated by unemployment, which just won’t go away. If one compares the development of unemployment rates in Europe (EU and EMU) with those in the USA over the past thirty years, as is done in Figure 5, it is obvious that Europe has repeatedly failed in the task of bringing unemployment back to a level that could be described as “high employment” or even full employment after a deep recession.

Figure 5

This is the decisive mortgage for the future, because in societies that have been characterised by high unemployment and a great lack of prospects for the mass of people for decades, politicians cannot plausibly explain to the people that new production structures and the loss of the old jobs, as they will be accompanied by the fight against climate change, do indeed represent an opportunity.

But the new BMWK apparently does not want to know all this or simply does not want to admit it. Instead, in the Annual Economic Report he tries to justify German mercantilism in a way that is more than embarrassing. On page 108 paragraph 285 of the report states:

“The current account balance is predominantly influenced by factors that cannot be directly influenced by economic and financial policy measures. It is primarily the result of market-based supply and demand decisions by companies and private consumers on the world market. At the same time, the German current account surplus is an expression of the high competitiveness of the German economy and its product portfolio, which is geared towards capital goods.”

The first sentence is wrong. The second is empty, and the third contradicts the first. For if the German surplus is an expression of Germany’s high competitiveness – which is beyond question, and the BMWK can therefore be agreed on this – and if the federal government did everything in its power at the beginning of the 2000s to increase German competitiveness by “flexibilising” the German labour market – which is also undoubted – then it was indeed economic policy measures that were responsible for the German current account surplus. These measures caused German wage dumping in the European Monetary Union and thus the real devaluation of Germany vis-à-vis its currency partners and the rest of the world. The accompanying expansion of the low-wage sector in Germany and the reduction of the German unemployment rate can neither excuse nor meaningfully justify this economic policy. It would be as if, in a robbery, the perpetrators wanted to use the loot for their own well-being as justification for their crime.

The fact that in this annual economic report Germany again professes its commitment to free trade and its noble principles, while at the same time trampling on the most important principle of free trade with its surplus, can no longer be surpassed in terms of clumsiness. Anyone who strives for absolute advantages – especially in a monetary union – and tries to maintain them at all costs has not only failed to understand free trade, but also the fundamentals of peaceful cooperation between peoples. On this intellectual basis, which is nothing other than the blind continuation of Merkel’s mercantilism, the traffic lights coalition will continue to block the entire continent politically in the coming years and ultimately destabilise it. But it is likely to continue: Before we show insight, we prefer to leave the field to the right-wing radicals in France and elsewhere, even if the collateral damage far exceeds our own benefit.