In the current debate about government debt, practically all experts are wrong because they simply ignore the macroeconomic interrelationships without which government debt can neither be explained nor justified. Almost all of them, even the seemingly enlightened ones, have remained Swabian housewives in one way or another. An editor at the Süddeutsche Zeitung has done a really good job of showing it. the Author, Kerstin Bund, may think she is emancipating herself from the logic of the Swabian housewife, but in reality she fails to walk away from it.

According to the article, the Swabian housewife took to the world stage when Angela Merkel proclaimed her an icon of common sense in 2008. However, that means to ignore the Scottish housewife that was created by Adam Smith some 250 years ago. The Scottish economist had already identified thrift as one of the most important virtues. According to his moral doctrine, there can be no investment without the conscious act of renouncing consumption. That is precisely where the problem lies.

The author of the Süddeutsche Zeitung advances into mined territory in an almost daring way, gathering all her courage by writing: ‘It may not be immediately apparent, but unlike private debts, national debts do not actually have to be repaid. Rather, they are passed on from generation to generation. High national debt is not a problem as long as economic output grows at a similar rate and the interest burden remains manageable.’

That is true. But that also applies to every private investor and debtor. As long as the investor owns a company that is doing well, and can easily generate the interest from its returns, it is perfectly normal to repeatedly replace expiring loan agreements with new ones. The real difference between the private and public sectors is quite a different one. The first sentence of the Süddeutsche Zeitung quoted above should have ended with the words: …unlike private debt, government debt cannot be repaid because private companies and private households in an economy are savers, i.e., they spend less than they earn.

Talking about debt without taking saving into account is pointless.

That is the crux of the matter. Anyone who talks about government debt without talking about the savings of the private sectors of an economy is missing the point from the outset. Anyone who thinks that the main issue is what the state does with the borrowed money, whether it invests it or consumes it, is way off the mark. Anyone who turns the debt issue into a generational issue has not even understood the bookkeeping. Anyone who thinks that they can arbitrarily cut back on consumer spending without calling into question the effect of debt-financed investments has thoroughly misunderstood the role of companies in a market economy.

In any meaningful analysis, income and profit of companies must take center stage. Income of the companies is affected at the beginning and at the end of every chain of purchases and sales in a market economy. The companies receive the residual income, i.e. the income that remains after all contractually agreed payments have been made in the case of an investment or any other transaction. The income of companies across all sectors is always a mixture of income generated by investments and income that originates directly in consumption. Company income is created because either the companies themselves or the other two sectors (the state and private households) have used their income to consume or to invest. Saving reduces the income of companies.

The source of corporate income is irrelevant for corporate investment decisions. Whether demand, capacity utilisation and profits in a company increase because the company benefits directly from government contracts or because the other companies or the employees as a whole have more income due to the government contracts is not important for its investment decisions. Conversely, if a company’s demand falls even though the state is investing more but at the same time cutting social benefits, which in turn leads to falling consumer demand, its investment decision will be negative. The belief that one outweighs the other or that it is generally less harmful to cut social spending than public investment, is untenable.

The feeble attempt of the neoclassical economists to construct an automatic conversion of saving into investment via the interest rate has failed due to corporate income. Any saving reduces this income and thus the willingness to invest. Those who do not start and end their analysis with the effect of saving or debt on corporate income will not get anywhere. Because neoclassical economists never do just that, they have remained – from Adam Smith to the present day – at the level of the Swabian housewife. Even the German Ordoliberals, who carry the market economy like a mantra, do not know the incomes and profits of companies. Macroeconomically relevant statements can only be made if the residual income of companies is at the centre of considerations.

The trade balance as a savings problem?

If you want to understand how far removed from reality economists’ usual ideas about saving and investing are, you have to look at how famous neoclassical economists explain the American trade deficit. I have mentioned some prominent examples in my textbook (chapter 3). Recently, Maurice Obstfeld, who (together with Kenneth Rogoff) wrote a standard work of neoclassical economics (‘Foundations of International Macroeconomics’) and was chief economist at the IMF, has also revealed himself as a savings theorist. He wrote a few weeks ago in the Financial Times:

‘It is low national saving coupled with robust investment that drives the US external deficit. Serious action to curb the federal budget deficit would boost both the trade balance and manufacturing employment. This approach requires plans that reduce borrowing meaningfully while avoiding needless economic damage – not the chainsaw theatrics currently on display.’

He received particular praise from Martin Wolf, the chief editor of the Financial Times:

‘As Maurice Obstfeld, former chief economist of the IMF, has noted, the US’s trade deficits are not due to cheating by trading partners, but to the excess of its spending over income: the biggest determinant of America’s trade deficits is its huge federal fiscal deficit, currently at around 6 per cent of GDP’.

This is a deduction that can only be called absurd. There are trade and current account deficits because the US does not have enough national savings to finance its investments. It is believed that the fact that a current account deficit is always offset by a capital account surplus can be interpreted as the import of capital that can be used for domestic investment. If the state reduced its deficits, i.e. claimed less capital for itself, the US would have enough capital of its own and could do without the import of capital.

Here, too, corporate income is not mentioned. Again, it is essential for a rational analysis. The idea that the state could reduce its deficit, i.e. cut spending or raise taxes, without this having any effect on corporate income, is from another world. But if corporate income falls as the government curbs its deficits, no one can seriously claim that investment activity will continue exactly as before. Yet that is the assumption if one says that the financing of (existing) investment will only be shifted in the wake of the government’s cutbacks – from foreign sources to domestic sources.

Even worse: what is recorded as capital inflow for the US in the balance of payments statistics has nothing to do with an import of capital that could be used for any purpose in the US (see in detail the excellent article by Joachim Nanninga from 2022, in German). A capital import in the balance of payments only means that a country has imported more than it has exported and that this has been financed in some way. The imports have been paid for and the capital import has thus been made. There is nothing left that could be used for domestic investment. Joachim Nanninga comments:

‘This is bound to make many readers bristle: a payment from a customer arrives in your account, and that’s supposed to be a capital export? As a buyer, I pay, and that’s supposed to be a capital import!? The instinctive resistance shows: with our mundane thinking, we are almost all still rooted in the world of the gold standard, even though we constantly talk about the money-printing press. The exported goods were not paid for in gold, however, but were exchanged for a claim, which, even if it is paid for, remains a claim – the only difference being that it is no longer directed at a private entrepreneur, but at a bank. The buyer has exchanged the purchased goods for his bank claim in the case of direct payment.”

The attempt to explain current account balances with savings and investment decisions is also wrong from the outset (as also shown in my book) because the world’s current account balances are a zero-sum phenomenon (the world’s current account balance is always exactly zero). However, logically, zero-sum phenomena can only be explained with zero-sum factors. Zero-sum factors are real exchange rates, the terms of trade or growth differentials between countries.

The dollar and the US current account

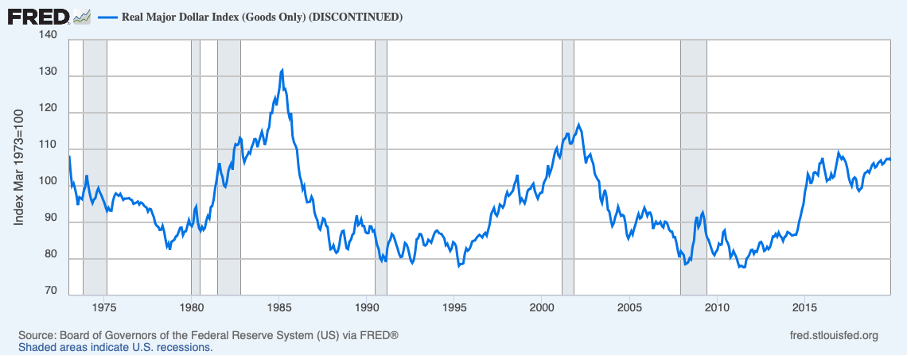

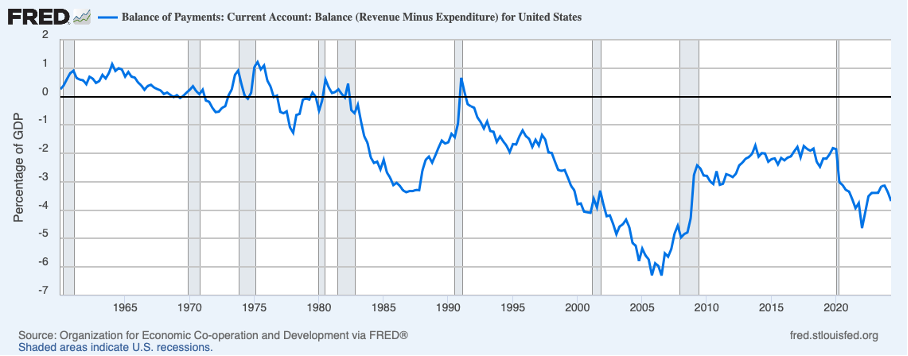

This can also be easily demonstrated empirically. The following figures show several periods where it can be seen unequivocally that the real exchange rate plays a decisive role in the change in the current account. In the 1980s, the US current account went deeply into deficit because the dollar appreciated sharply in real terms (Figure 2). The reversal of the dollar’s value, which followed the so-called Plaza Accord, a political intervention to devalue the US dollar, brought the American current account back into balance within a few years (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Real exchange rate of the US dollar

After that, between 1995 and the turn of the century, the real dollar appreciated sharply. Once again, the US current account deficit widened to a record level of over 6 per cent of GDP before the global financial crisis of 2008–2009.

Figure 2: US current account

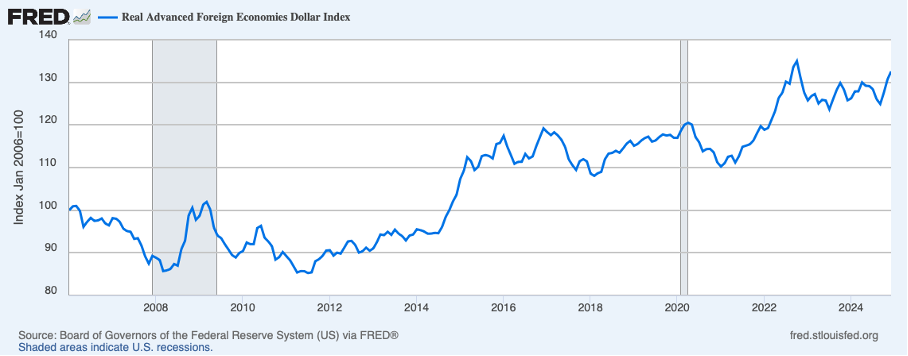

Since 2020, as Figure 2 shows, the US current account deficit has again increased remarkably. The real exchange rate of the US dollar rose by more than 30 per cent after the financial crisis and, especially after 2020, rose by another 10 per cent.

Figure 3: Real exchange rate of the US dollar after 2020

In this respect, the considerations of the administration under Donald Trump to consider a political action similar to the Plaza Accord (‘Mar a Lago Accord’), which aims to devalue the US dollar and reduce the American current account deficit, cannot be dismissed out of hand. The neoclassical saving theorists are clearly on the wrong side with their criticism of these plans. Tariffs on certain goods from the surplus countries, such as those Trump has just announced for cars from Europe, can also be justified.

Neither the frugal Swabian housewife nor her thrifty Scottish counterpart can offer any advice on economic policy that should be taken seriously. Neoclassical economics, though intellectually bankrupt, persists with its nonsensical assumptions because it senses that any concession to reality would mean its swift demise. Neoliberals defend their doctrines like a religion anyway and cannot be dissuaded, no matter how good the arguments are. But even most of those economists who would call themselves progressive have not yet arrived at the macroeconomic level. Only the consistent inclusion of the residual income of companies in every step of an analysis of savings and credit decisions means taking the leap to the macroeconomic level.