If the German Federal Statistical Office hadn’t officially announced it last Friday, you wouldn’t have believed it. In Germany, the part of collective wage agreements that leads to a permanent collective wage increase actually amounted to only 2.4 per cent last year. This affects around 43 per cent of all employees whose employment contracts are subject to collective bargaining.

If the special payments made by companies to compensate for inflation are added, the total increase in collectively agreed wages is 3.7 per cent. However, only the 2.4 per cent represents the wage level which collectively agreed wage increases will be based on in future. The special payments – just like the extraordinary price increases – were a temporary phenomenon.

In retrospect, the collectively agreed wage increases with and without special payments turn out to be very moderate when compared with the media hoopla about allegedly almost double-digit growth rates that was created by trade unions and their declared opponents around the wage negotiations. The average for all employees together is much more modest than the result for the lower wage groups, whose protection against the rise in energy and food prices was the primary concern in the last negotiation rounds of wage agreements.

According to the German Federal Statistical Office, nominal wages overall rose by 6 per cent last year. This figure includes not only the development of collectively agreed wages with all special payments, but also wage changes in areas not covered by collective agreements, in particular the increase in the minimum wage to 12 euros and the effects of various government reductions in labour costs. The breakdown into one-off and permanent effects is apparently only possible for collectively agreed wages due to the statistical possibilities of the Federal Office, which is why their development is of particular interest in the current situation.

What companies have paid or are still paying their employees as temporary wage compensation in response to the temporary acceleration of many price increases will no longer play a role in companies’ future cost calculations as soon as the one-off payments are over. In this respect, only what has been agreed permanently is relevant to inflation in the future. Consequently, the argument put forward by the ECB and many German observers that monetary policymakers will have to wait and see what happens to wages in the first half of this year before they can initiate a turnaround in interest rates is unconvincing: if the permanently agreed wage increases in the largest country in the EMU were 2.4 per cent in 2023 with an increase in the inflation rate at consumer level of 5.9 per cent, a significantly higher increase in wages in 2024 is more than unlikely. With a current inflation rate of 2.5 per cent, the next permanent wage increase will certainly be below 2.4 per cent in all of the major sectors that have concluded two-year agreements in 2022 and 2023.

ECB blind to wage trends for a decade …

The ECB and with it many media representatives point to the wage increases in the eurozone recorded by the ECB, which show that wages in the EMU rose by 4.5 per cent on average in 2023 as well as in the fourth quarter (Figure 1).

Figure 1

However, the graph also shows what we have often pointed out, namely that European wage settlements were below two per cent 40 times in the 48 quarters from 2010 to 2021, i.e. in a good four-fifths of the time. Even if the weak coronavirus crisis years are disregarded, the average annual growth rate of collectively agreed wages in the eurozone for the period before that, i.e. 2010 to 2019, was just 1.7 per cent.

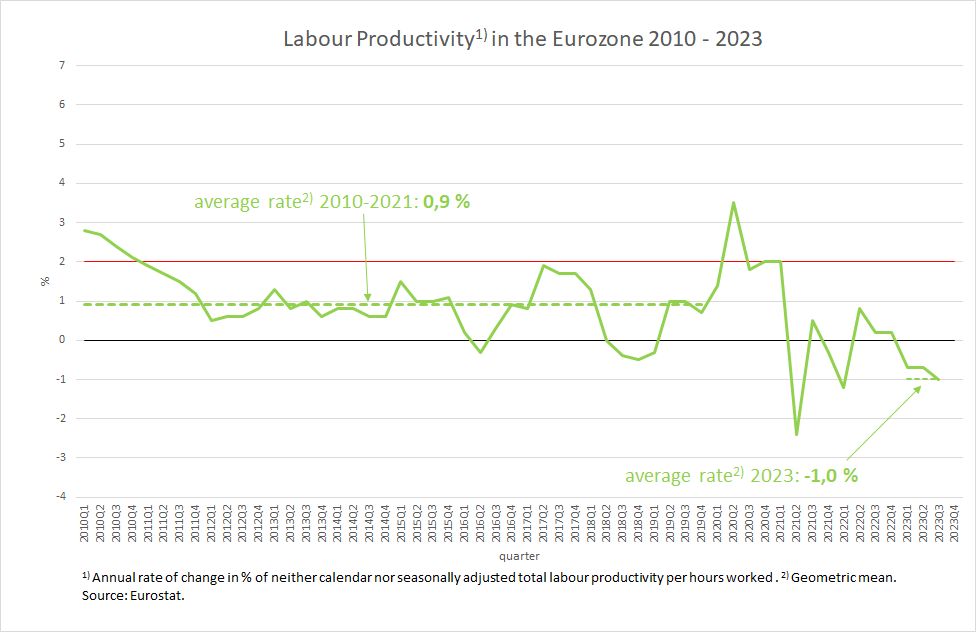

Figure 2

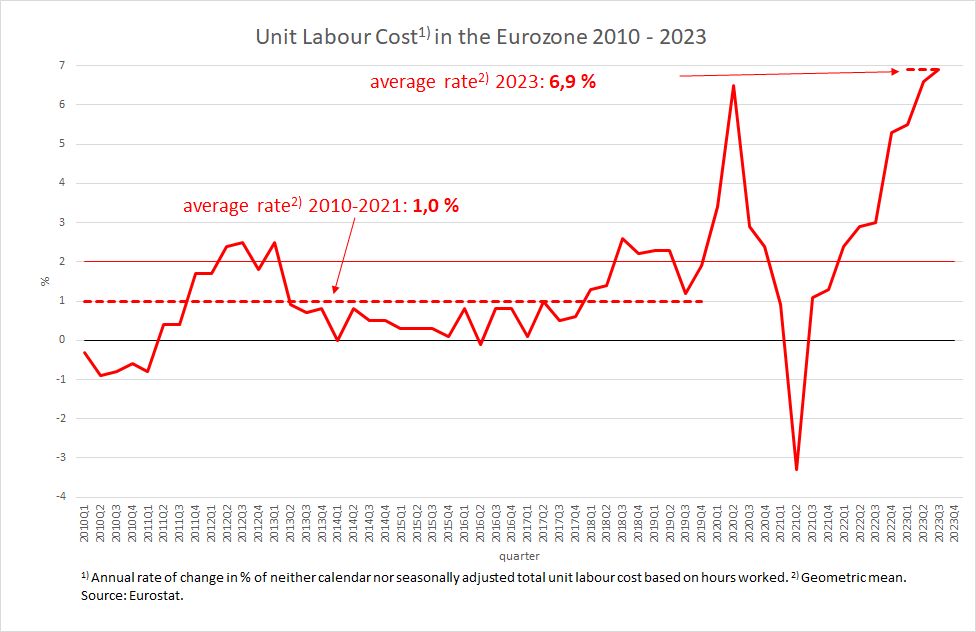

As productivity rose by an average of 0.9 per cent in the same period (Figure 2), overall unit labour costs in the economy were well below two per cent, namely an average of 1.0 per cent between 2010 and 2019 (Figure 3).

Figure 3

This was the reason why the ECB was unable to achieve its inflation target during this period and had to constantly combat deflationary tendencies with zero interest rates. However, we do not remember the ECB clearly criticising the course of the European trade unions at the time.

… but alarmed now?!

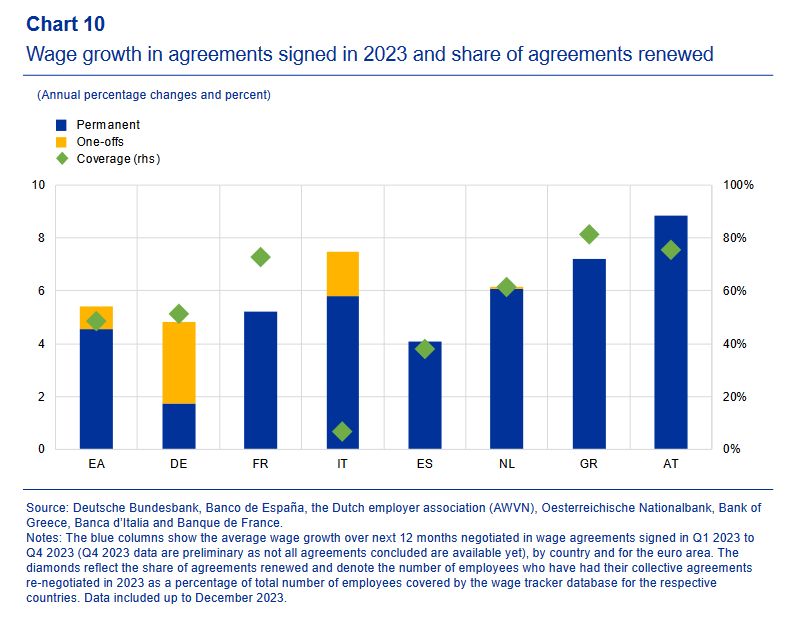

However, the current trend in collectively agreed wages says little or nothing about a future risk of inflation that could emanate from wages if, as in Germany, there are high temporary components in wage increases. The ECB is also aware of this. Researchers from its ranks have therefore presented a new study that breaks down wage increases agreed in 2023 into temporary and permanent components for seven eurozone countries, including the four largest (Germany, France, Italy and Spain) (original chart from Occasional Paper No 338, p. 32).

On average for these countries, this results in permanent wage increases of around 4.5 per cent for the agreements concluded in 2023. Surprisingly, only for Germany does a really large proportion of the agreements in the past year consist of one-off payments – the yellow share of the columns is only very high for Germany. The permanent burden of new contracts concluded in 2023 (not identical to the results of the German Federal Statistical Office for 2023, which also include the old contracts) is even less than 2 per cent in Germany (representative of around 50 per cent of employees, see the green diamond in the chart).

ECB overlooks the real problem

The differences between European countries are enormous. In France, for example, there were no one-off payments for settlements of five per cent for over 70 per cent of employees. In Austria, the agreements (with a very high coverage rate of almost 80 per cent) were even almost 9 per cent. Italy has permanent agreements in the order of almost six per cent, but the coverage is very low, which is why it is unclear how significant this figure is.

The large differences between these numbers will be a huge problem for the competitiveness of some eurozone countries in the future. One thing is certain: with a permanent burden from collectively agreed wages of just over two per cent in Germany, talk of declining German competitiveness is untenable. On the contrary, it is to be expected that such comparatively low agreements will further increase Germany’s already high competitiveness and cause corresponding problems for other European countries.

No wage pressure on average in the EMU

However, a European inflation problem cannot be derived from these wage figures, and therefore also not the justification for continued high interest rates. If wage settlements in the eurozone do not exceed 4.5 per cent in 2023 with an annual average inflation rate of 5.4 per cent and a reasonably intact economic development, it is to be expected that the settlements for 2024 will be significantly lower.

For this year, even the central bank assumes that the annual average inflation rate will be below three per cent. The economic situation and the situation on the labour market have deteriorated significantly. For new contracts, this undoubtedly means lower rates than in the previous year. The balance of power has shifted in favour of employers and the objective data show that there is no danger of inflation, as was expected at the beginning of 2023.

Even if the agreements in some contracts from last year carry over into this year, last year’s 4.5 per cent mark the peak of wage growth. In addition, companies will find it much more difficult to pass on wage increases to prices this year due to the deterioration in the economic situation.

For the ECB, this means that it could start cutting interest rates immediately without any risk. If it does not do so, it will cause even greater damage than it already has. The talk of a second wave of inflation if it cuts interest rates too early has no basis whatsoever. It is based on the second wave of inflation in the 1970s, which occurred a few years after the first wave. At that time, however, there was a second exogenous shock, which the monetary policy hawks forget to mention: the oil price doubled again in 1979 and 1980. But even after this second shock, wage increases in Germany and many other countries were far lower than after the first price shock.

Poor analysis and communication by the ECB

Overall, it is clear that the ECB’s communication during this phase of high price increases has been inadequate, at least since the beginning of 2022. It has allowed itself to be carried away by the general talk of inflation and has itself spread the impression that Europe is facing real inflation, which can only be combated with great rigour. In such an environment, it is no wonder that the trade unions took to the barricades, fearing permanent real wage losses.

If the central bank had maintained the position from the outset that the price increases were exogenous shocks that would only have temporary effects, it would have been possible to campaign throughout Europe for the type of agreements that were realised to a considerable extent in Germany, namely agreements with a high proportion of one-off payments that took account of the temporary nature of the price increase rates and with a particular focus on the lower wage groups. The German trade unions are to be congratulated for embarking on this path, even though the prevailing opinion in Germany, including that at the top of the Bundesbank, uncritically assumed “inflation”.

In EMU, the central bank and the European Commission must communicate much more clearly and comprehensively in such a situation in order to prevent a divergence in national wage trends, as can now be observed again. If the central bank recognises and acknowledges the importance of wages for price development, as is obviously the case at the moment, it must not simply let every wage development at national level run its course. It must take the so-called macroeconomic dialogue seriously and use clear analysis and persuasion at this level to make it clear to the negotiating partners and governments how fatal it is when some countries in a monetary union increase their competitiveness through comparatively low wage settlements, while others lose competitiveness vice versa.