It’s probably all too human. Whenever you don’t know what to do next, you fall back into old ways of thinking. In 1982, when a social-democratic-liberal coalition was at an end and was replaced by a black-yellow coalition under Helmut Kohl, supply-side policy and improving competitiveness were the big hit. In 2002, when a red-green coalition no longer knew what to do in terms of economic policy, an Agenda 2010 was copied from a report by the German Council of Economic Experts, which contained nothing other than supply-side policy and improving national competitiveness.

In 2024, when a red-green-yellow coalition no longer knows what to do because it is being held back by a debt brake, the recently published annual economic report states: “Time for a comprehensive and targeted supply-side policy”. If you search for the word “competitiveness”, you will find it 21 times in this text.

Those who don’t have any money or don’t dare to have any, i.e. to take out a loan, dabble with what doesn’t cost them money and hope that this will turn things around. The government believes that all you have to do is pull the right levers and the economy will run like clockwork, even though there is no lubricant at all. Cutting back on bureaucracy and lowering taxes on companies – counter-financed, of course – would unleash the forces of innovation and entrepreneurial initiative that would lift an economy like a phoenix from the ashes. This is wrong, as shown here, for example.

Those who are conjuring up this old hat again today are evidently firmly convinced that the change of direction on the supply side was successful both times in the past. Under the Kohl government, the economy initially developed relatively weakly in the 1980s, but then had two strong years before German reunification. To this day, not only many Social Democrats believe that Agenda 2010 was a success, but practically all members of the CDU/CSU and the FDP. They agree with large sections of German economists, as this policy carried Germany to the top of Europe as if on a cloud until the coronavirus crisis.

What hardly anyone in Germany knows or wants to know is that the first two attempts at supply-side policy and competitiveness were entirely at the expense of Germany’s trading partners. Whenever Germany tries to make ends meet without its own money, its trading partners have to run for cover. This is when mercantilism is the order of the day, i.e. undercutting others by tightening one’s own belt. The only stupid thing this time is that the old mercantilism still has such a negative impact that it will kill off the new one in no time at all. The jug goes to the well until it breaks.

Devaluation of the Deutschmark against the US dollar under Kohl

Chancellor Kohl had exactly the same ideas in 1982 that are still in vogue today. You only have to read the old Lambsdorff paper to realise that liberals in all parties are no more imaginative today than they were back then. There is no need for any elaborate reflections on the success of the “intellectual and moral turnaround” under Helmut Kohl. As the USA under Ronald Reagan was fully committed to fiscal expansion and American interest rates were relatively high, the path to more German growth was paved from the outside: The US dollar rose – fuelled by speculation to boot – from an annual low of 1.70 deutschmarks per dollar in 1980 to an annual high of 3.40 deutschmarks per dollar in 1985. “The market has gone crazy,” wrote Der Spiegel in the same year.

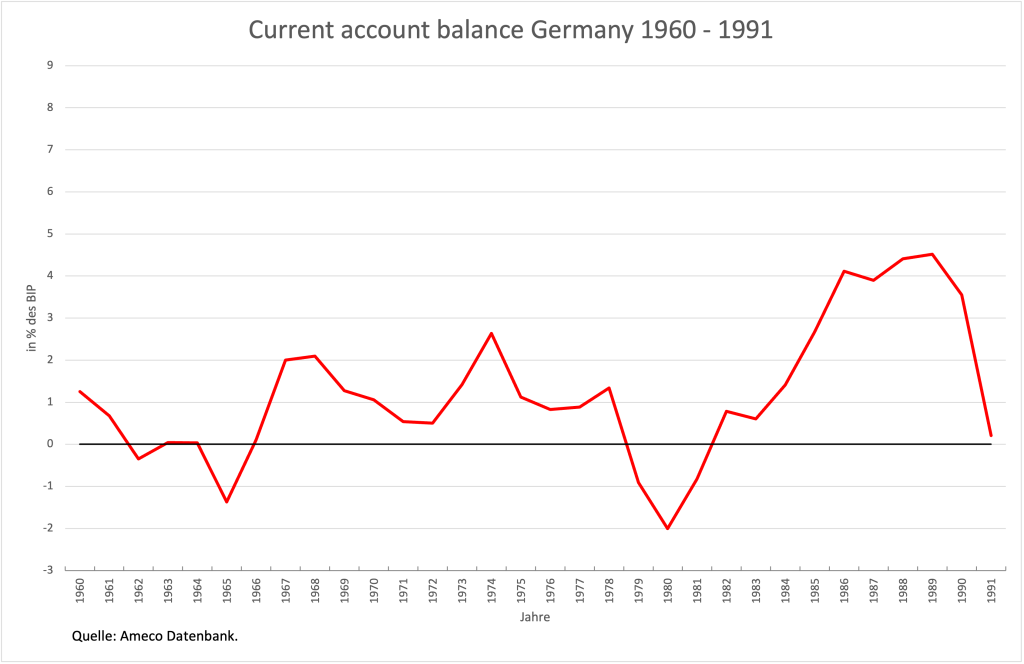

This put an end to concerns about German competitiveness. The devaluation of the Deutschmark by an incredible 100 per cent improved the position of German companies almost everywhere in the world. Exports boomed and the German current account balance, which in 1980 still showed a deficit of 2 per cent of GDP, rocketed to a surplus of over 4 per cent in 1986. However, this drove the American government onto the barricades, forcing Germany to agree to the so-called Plaza Agreement within the framework of the G7 in 1985, which ultimately led to the US dollar returning to its former value.

Figure 1

Real devaluation in the monetary union after the Agenda

In order to compare Schröder’s Agenda policy with Kohl’s turnaround, one can refer directly to the FDP-affiliated Friedrich Naumann Foundation (“für die Freiheit”). It writes:

“Agenda 2010” was in many ways, especially in its thrust, a new edition of that paper, which at the time was already 25 years old but had lost none of its topicality. The extremely positive consequences for the situation in Germany are well known. In this respect, from today’s perspective, the “Lambsdorff Paper” was far more than a tactical ploy in the party campaign: It strongly influenced the political agenda of the Federal Republic for a long time and by no means to the detriment of the Germans. It is undoubtedly one of the most important contributions that the Liberals have made to this country.”

That’s right. After the Liberals had already been successful with mercantilism in the 1980s, they wanted to try again under the red-green coalition. And again, the policy was successful. The devaluation of the Deutschmark in the days of Helmut Kohl was nothing compared to the relative wage reduction that Schröder brought about in the European Monetary Union “by no means to the detriment of the Germans”.

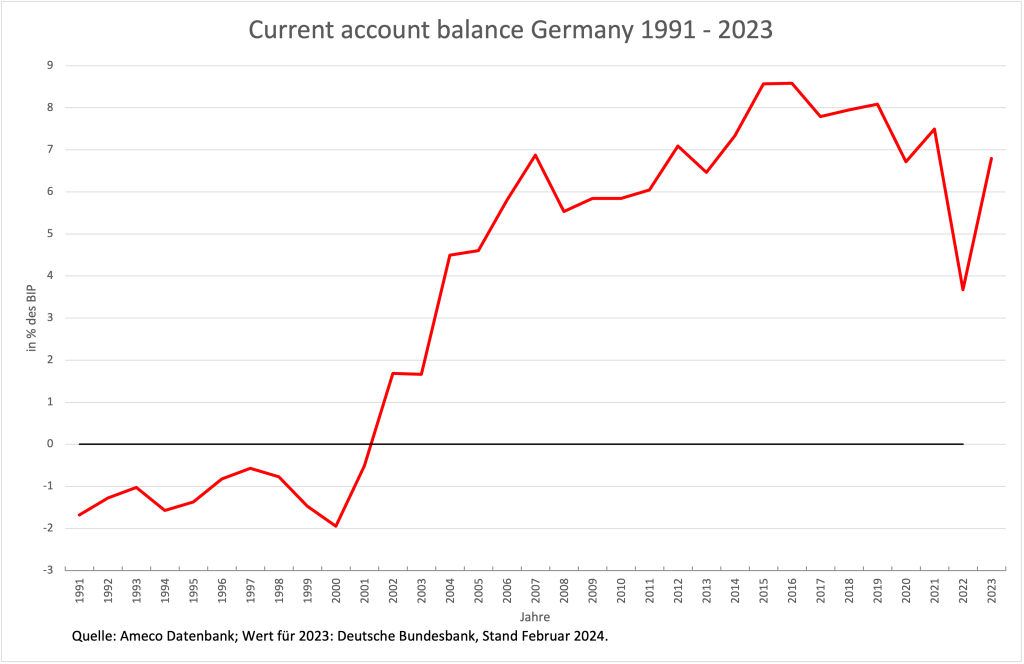

With the abolition of the Deutschmark and the introduction of the euro, only the country’s visible nominal exchange rate had disappeared, but not the so-called real exchange rate, i.e. competitiveness. This could very well be devalued by “wage restraint”. As a result, the current account balance exploded, which had even slipped into deficit in the course of the expansionary demand policy of German unification and was still at minus two per cent in 2000 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

This time it did not remain at the “meagre” four per cent of the 1980s. It had already reached seven per cent of GDP by 2007. And, what is special, practically nothing has happened between 2007 and today that would have helped to reduce the German surplus again. In 2015 and 2016, the highest level was reached at 8.6 per cent in each case, which was a massive breach of European rules but was never penalised.

As a result, the surpluses are still huge today and were only briefly reduced once in 2022 due to the rise in commodity prices and the associated negative terms-of-trade effect. Last year, the surplus was already close to seven per cent again at 280 billion euros. The German government is even hoping for a further increase to 7.4 per cent this year.

However, the failure to maintain macroeconomic equilibrium does not bother the European public, as hardly anyone is aware of a European rule that prohibits major external imbalances and should be sanctioned under the “Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure”. On the other hand, almost everyone knows how high the prescribed limits on fiscal debt should be (the 3 and 60 per cent criteria). However, if you ask about the level of the permissible current account surpluses, you are met with raised eyebrows – not to mention the absurd asymmetry that higher surpluses are permitted (up to 6 per cent of GDP) than deficits (only up to 4 per cent).

While the whole world is aware of which countries are particularly in breach of the 60 per cent limit for public debt (Italy and Greece), the ranking of European surplus candidates is largely unknown. In 2023, Norway is at 20 per cent (fossil gas supplies have made the “green” country even richer than it already was with double-digit GDP shares since 2021), Denmark at 10 per cent, the Netherlands at 9 per cent and Germany at almost 7 per cent.

Increasing competitiveness when competitiveness is already extremely high?

If there was even one person in a leading position in the German government who understood these relationships, the word competitiveness would not be used 21 times in an annual economic report. What should Germany’s trading partners do to fend off the renewed attack on their economies that they can expect from Germany in the coming years? Will they tacitly accept it if the German surplus, instead of falling, rises to over ten per cent and thus finally shows the last naive person in the other countries that there can never be acceptable rules for everyone in EMU with Germany?

To make matters worse, the German surpluses and the deficits of the others (as shown here) mean that France in particular has even less fiscal room for manoeuvre. If its current account deficits increase or the comparatively small surpluses of countries such as Italy and Spain decrease again, this will mean a deterioration in the economic situation in these countries and the need to do something about it. But this is precisely what Germany is preventing, as it is the driving force behind the deterioration of the economic situation elsewhere in Europe, but at the same time it is forbidden by the Brussels rules, which it itself constantly violates, from using government debt to combat economic weakness.

Anyone who believes that this contradiction, which borders on cynicism, can be continued indefinitely is wrong. Its consequences are fuelling a nationalism that is constantly on the rise and will ultimately destroy the European idea. If, in turn, it is made impossible for the deficit countries to stabilise their economic development to some extent through fiscal policy, national centrifugal forces will quickly gain the upper hand.