The ECB’s decision on 2 February to raise interest rates again by 0.5 percentage points and to announce an equally large increase for March will go down in history as a grand misjudgement. Although it is already foreseeable that the price development in Germany and Europe will quickly approach normal values in the course of this year, the central bank risks a further deterioration of the economic development. It underestimates the current dynamics of the price decline.

The ECB writes in its press statement: “Keeping interest rates at restrictive levels will over time reduce inflation by dampening demand and will also guard against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations.” In other words, the ECB is relying on rising unemployment to slow wage growth. But wage developments across the euro area offer no evidence to suggest that there could be an acceleration in wage increases that would have an inflationary effect.

The latest available figure for European labour costs shows an increase of 2.9 per cent in the third quarter of last year. In Germany, the two largest industrial unions have reached agreements for 2023 and 2024 that in no way carry the risk of inflationary acceleration. The ECB is fighting a phantom and overlooks how quickly the price situation can ease already during the first half of this year if there are no new negative shocks.

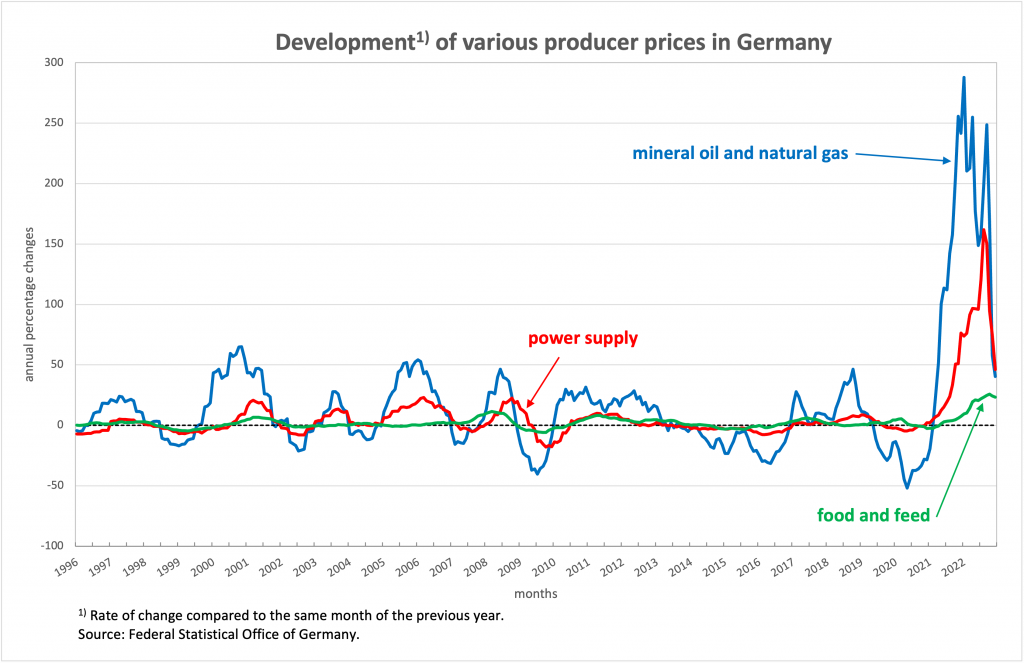

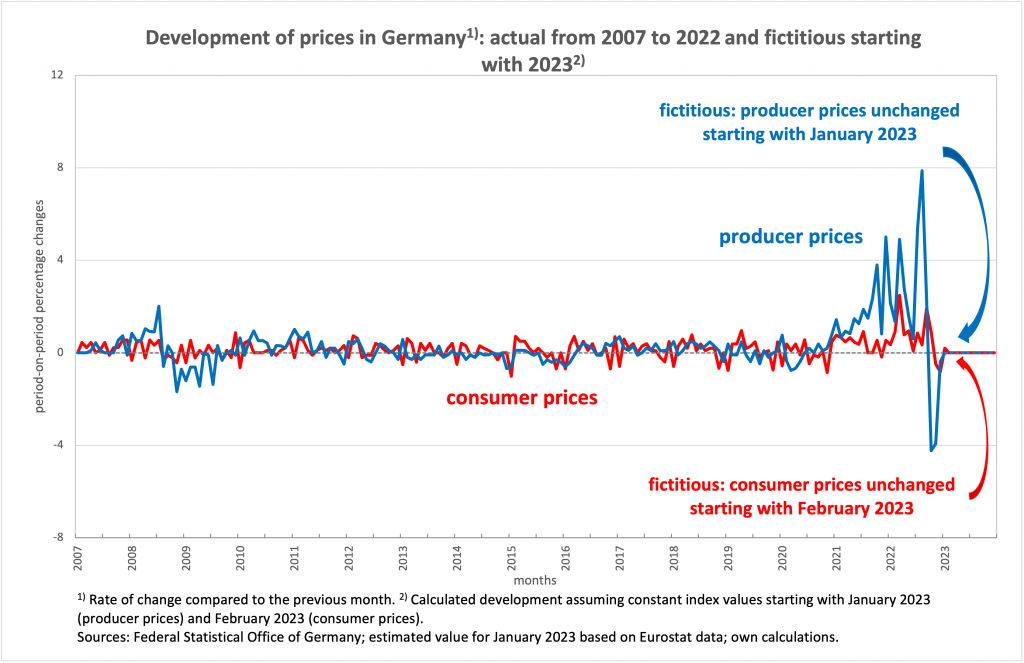

Figure 1 shows how much price development has already slowed down in critical areas. The huge growth rates between autumn 2021 and late summer 2022 have now been replaced by much more moderate rates, so the current rates (the changes compared to the previous month) have been approaching zero since the fourth quarter of 2022 and have even become negative in some cases.

Figure 1

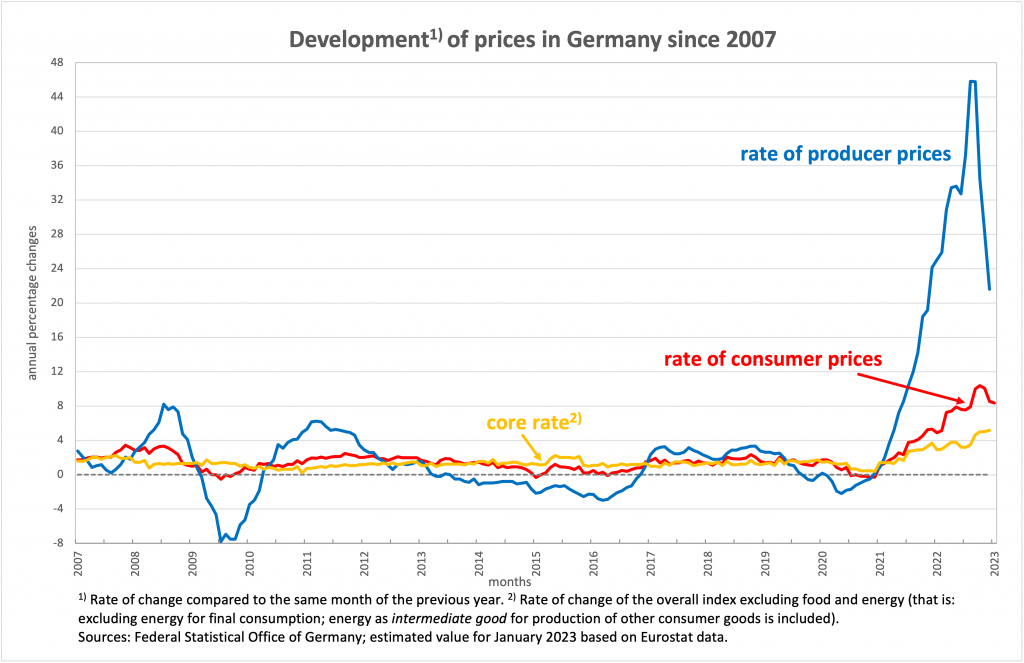

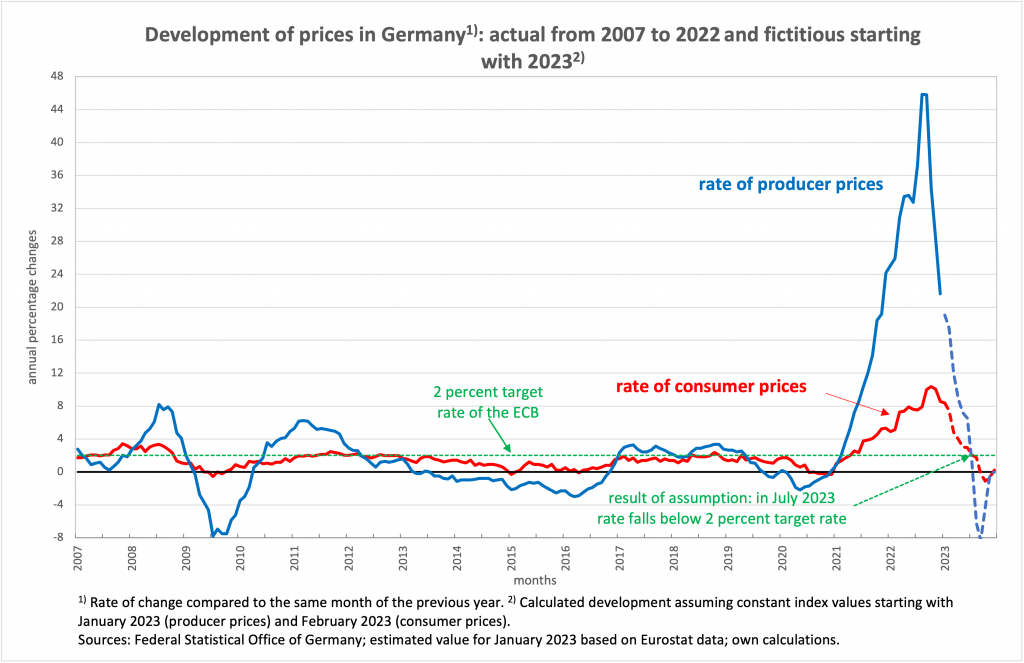

This effect can also already be observed in a weakened form in the rate of consumer prices (Figure 2). For technical reasons, the German Federal Statistical Office has not yet published a value for January 2023, but we can see from Eurostat’s estimate that Germany is expected to see price increase of around 8.4 per cent. That is what we have assumed here.

Figure 2

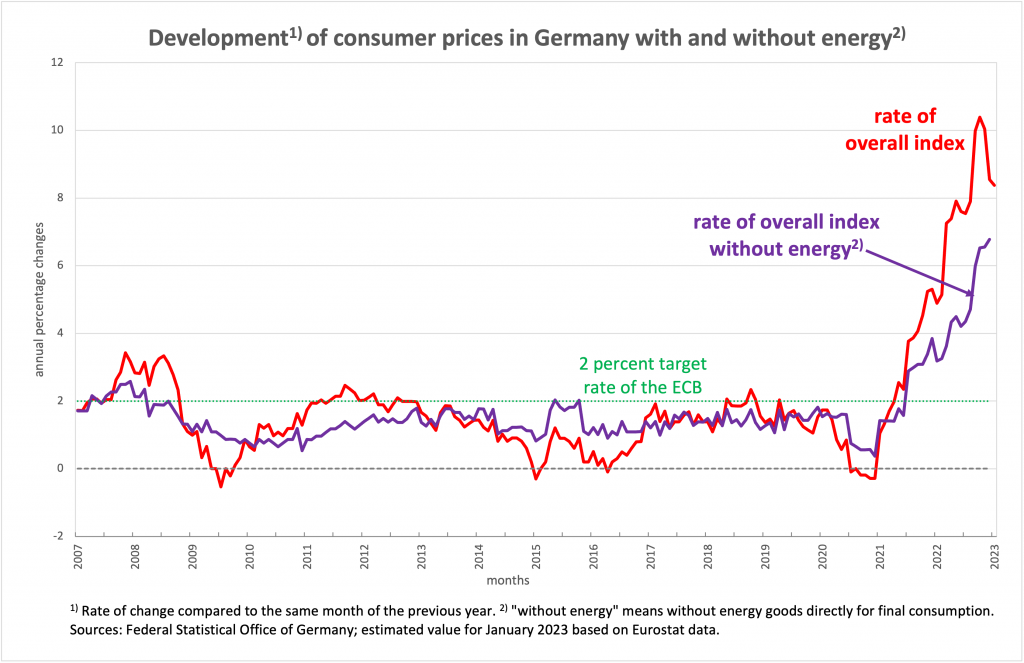

If we look at the overall consumer price index together with the overall index without energy (Figure 3), it becomes clear that the overall index without energy is also by no means independent of energy. “Without energy” simply means without the energy goods that are directly intended for final consumption. Energy as an intermediate input for other consumer goods is still included in this index or its rate of change.

Figure 3

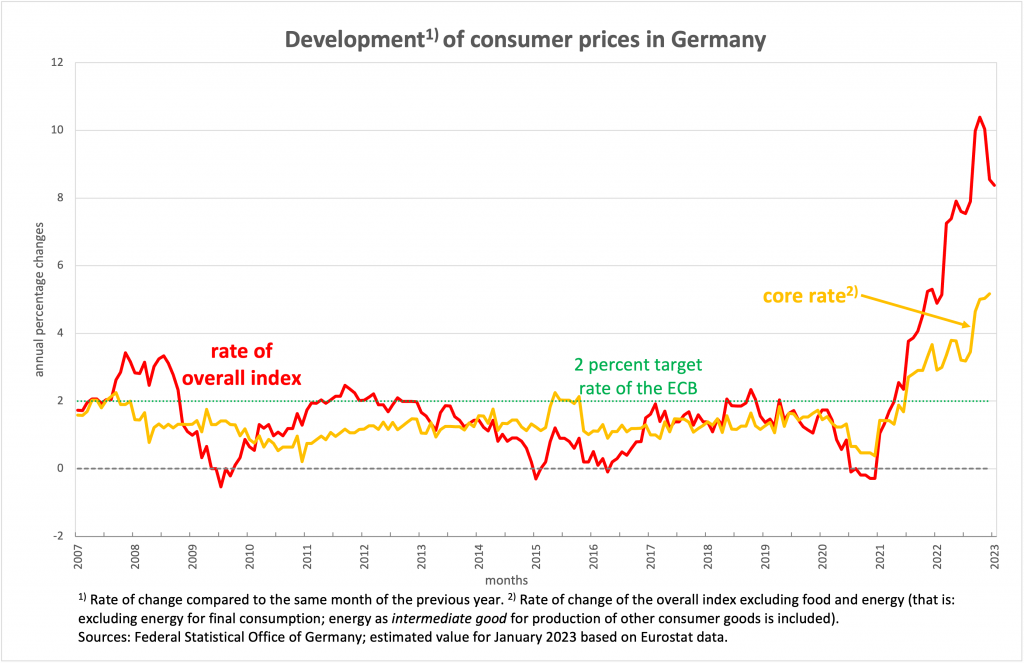

This also applies to the so-called core rate, which is currently used by many to prove an unchanged inflation dynamic (Figure 4). The core rate also contains a lot of energy, of course. For example, when inns raise their prices because their gas bills have gone up, the price increase goes into the core rate. This is often overlooked. The Austrian Standard, for example, writes: “…the core inflation rate [measures] the development of prices excluding energy and food, i.e. the particularly volatile components [are] omitted…. The core inflation rate includes restaurant visits, holidays and the development of consumer goods.”

Figure 4

In order to visualise the current dynamics of the price decline, one has to look at the so-called current rates, i.e. the rates of change compared to the previous month and not those compared to the same month of the previous year (Figure 5). Here we see that the rates for both the producer and the consumer price index have recently been in negative territory, i.e. prices have fallen in absolute terms.

Let us now assume that from February 2023 until the end of this year the producer and consumer price indices do not fall any further, but remain constant in absolute terms (in Figure 5 the fictitious horizontal lines on the right-hand side).

Figure 5

We use this assumption to calculate the rates of price increase compared to the same months of the previous year. The result can be seen in Figure 6: The rate of producer prices continues to fall on the currently plotted line into negative territory. The rate of consumer prices also falls continuously and reaches the ECB’s target inflation rate as early as July 2023, after which it begins to fall below it.

Figure 6

This assumed development of the monthly rates would result in an average growth rate of the consumer price index of 2.6 percent for the whole of 2023 compared to 2022, and of 3.7 percent for producer prices. If one compares this fictitious development with the current and already announced monetary policy of the central bank, the question of the appropriateness of this monetary policy urgently arises. How would a key interest rate level of 3 per cent or even 3.5 per cent fit in with a consumer price rate falling below 2 per cent from summer onwards?

Of course, it depends on how likely one considers the stop of price increases assumed here. What speaks in favour of prices continuing to rise beyond the high level reached? Some analysts assume that some suppliers of goods have not yet fully passed on the cost burdens from increases in energy prices and other commodities in the prices of goods and will do so later. It may be that suppliers are only gradually approaching the limits of their customers’ willingness to pay, i.e. they are testing at what point cost-related price increases lead to declines in the number of units sold that reduce their overall profit again. And it is quite possible that this process depends strongly on the behaviour of the competitors: If the competitors on the market increase their sales prices significantly and if it is a matter of goods of daily use that consumers can hardly substitute, then perhaps even higher prices can be imposed on the market in the short term than what can be attributed to the increase in energy prices and the prices for imported raw materials alone.

But if the latter should be the case, competition should put a quick end to such crisis gains. For customers do not have a similarly growing budget at their disposal, as can be clearly concluded from the results of the wage negotiations. This speaks against a further increase in prices across the board on a scale even half as high as in 2022.

If there is still no end to price increases in the area of goods of daily use, this is a clear case for the Cartel Office, not one for the central bank. Oligopoly structures in the retail sector, both for food and fuel, are not something to be protected. Not taking regulatory action here and instead putting the dynamics of real investments at risk by raising interest rates is the wrong economic policy approach. This is especially true in view of the enormous investment needs that rapid structural change requires to protect the climate.

It goes without saying that the European Central Bank’s monetary policy cannot and must not focus solely on Germany and its expected price developments. In another article we will analyse the outlook for price developments in other EU countries and how the current interest rate policy should be assessed from this point of view. For Germany, at any rate, it can already be said that there is a threat of damage here that should be avoided.