Capitalism is celebrated by the liberals as a success story. But, since the liberals came to power, capitalism has lost an enormous amount of its allure. There is no right policy when the thinking behind it is wrong.

Originally posted in German at Makroskop

Translated and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

The public sphere of Western democracies, i.e. politics, the media and the vast majority of social scientists, tends to interpret political events purely politically. Thus the great turning point at the beginning of the 1980s, when Ronald Reagan, Helmut Kohl and Margret Thatcher came to power, is also seen as a normal event that was attributable to the political failure of the left and thus to Keynesianism in the wake of the oil crises – leading logically to a new economic policy.

From a purely political point of view this is correct. But taking into account the intellectual background, i.e. the theory on which the economic policy is based, one can no longer speak of a normal event. The “intellectual and moral change” wrought by Helmut Kohl and the other conservative “leaders” was indeed a normal shift from a centre-left to a centre-right policy. Intellectually, however, it was a step backwards, because it was based on the ideas of the 1920s (which had long since failed and been discredited).

Supply policy

There was simply nothing new. The policy that was to replace Keynesianism with its emphasis on demand was called “supply policy” and referred to Say’s Law from the 18th century (“Supply creates demand”). But, as I showed in 1982 (in the essay “What is supply policy?” published in the magazine “Konjunkturpolitik”), that was an intellectually bankrupt idea. For it was only the return to microeconomic thinking that had been exposed for its narrowness by the advent of macroeconomic thinking brought by the Keynesian revolution.

We would be thought mad if today’s physics were to turn back to Newtonian principles and all subsequent theory developed and proven many times since were declared irrelevant. One could score academic success in economics simply by rediscovering the old heresies and ignoring the undeniable advances of Keynesianism to be found in modern macroeconomic thought. In other words, the demand side was again taken out of the decision-making process in which the (investing) entrepreneur found himself, after the discovery (back in the 1930s) that the demand side is absolutely necessary in order to make any relevant comment at all.

I wrote about it almost twenty years ago in an essay on the subject of supply and demand:

“This is the crucial difference between supply and demand policy. While the former hopes for “medium-term, structural” effects without taking the actual overall situation into account, demand policy focuses on improving the overall conditions under which companies operate in the perceived time-frame in which they have to act. This is indeed “short-term”. In the real world, however, there is no other time-frame for entrepreneurs. What the supply policy-makers call “medium-term” only means: if everything else goes well, my decision will improve the overall result a little. However, supply policy cannot say anything about whether everything is going well; rather, it depends on everything going well, i.e. the impetus coming from elsewhere.”

How could one hope to make economic policy on the basis of a theory that is already so limited, which is better than one based on a broader and therefore more relevant horizon? But the most striking heresy is the intellectual poverty of the mental turnaround in monetary and labour-market theory. In order to rob the state of any pretext for pre-emptive intervention in the money market, they went back to the centuries-old „quantity equation“, which had never served as a basis for monetary policy, and on the other hand to a model of the labour market, which in turn simply ignored demand effects and turned the labour market into just a market, like any other.

The monetarists around Milton Friedman (who himself was a brilliant salesman) simply claimed that one could find a money supply whose growth could be controlled at any time by the central bank and would be closely linked to the development of inflation, because the so-called velocity of money was easily predictable. There was never a scientifically sound justification for this. And yet this assertion became the basis of a policy in Germany for thirty years which, under the guise of consistent inflation-control by the independent central bank, drastically restricted development opportunities and was thus enormously costly.

The decisive link

Some time ago (here in German) I showed and briefly explained the decisive empirical relationship (Figure 1). In the first thirty years of the second half of the last century, the relationship between interest rates and growth (both nominal here) in the USA was exactly the opposite to that in the thirty years that followed. In the first thirty years, interest rates were almost always lower than the growth rate (which can also be seen as a kind of macroeconomic return on investment), and in the thirty years that followed they were almost always higher.

Figure 1

Growth and government bond yield in the USA

The same picture can be seen in all major Western economies – except Great Britain, which did not experience an economic miracle during the Bretton Woods period and was therefore regarded as the “sick man” of Europe. During the Bretton Woods era there were favourable investment conditions, which returned only after the great financial crisis of 2008/2009. But the return to a normal ratio does not seem to have the same effect as before, given the low rate of inflation and growth that the global economy has now embarked on.

If one divides the decades accordingly, the result for Germany is clear (Figure 2). With the exception of the recession years 1966 and 1967 as well as 1974 and 1975, interest rates in the first phase were well below the growth rate.

Figure 2

Growth and government bond yield in Germany 1956-1979

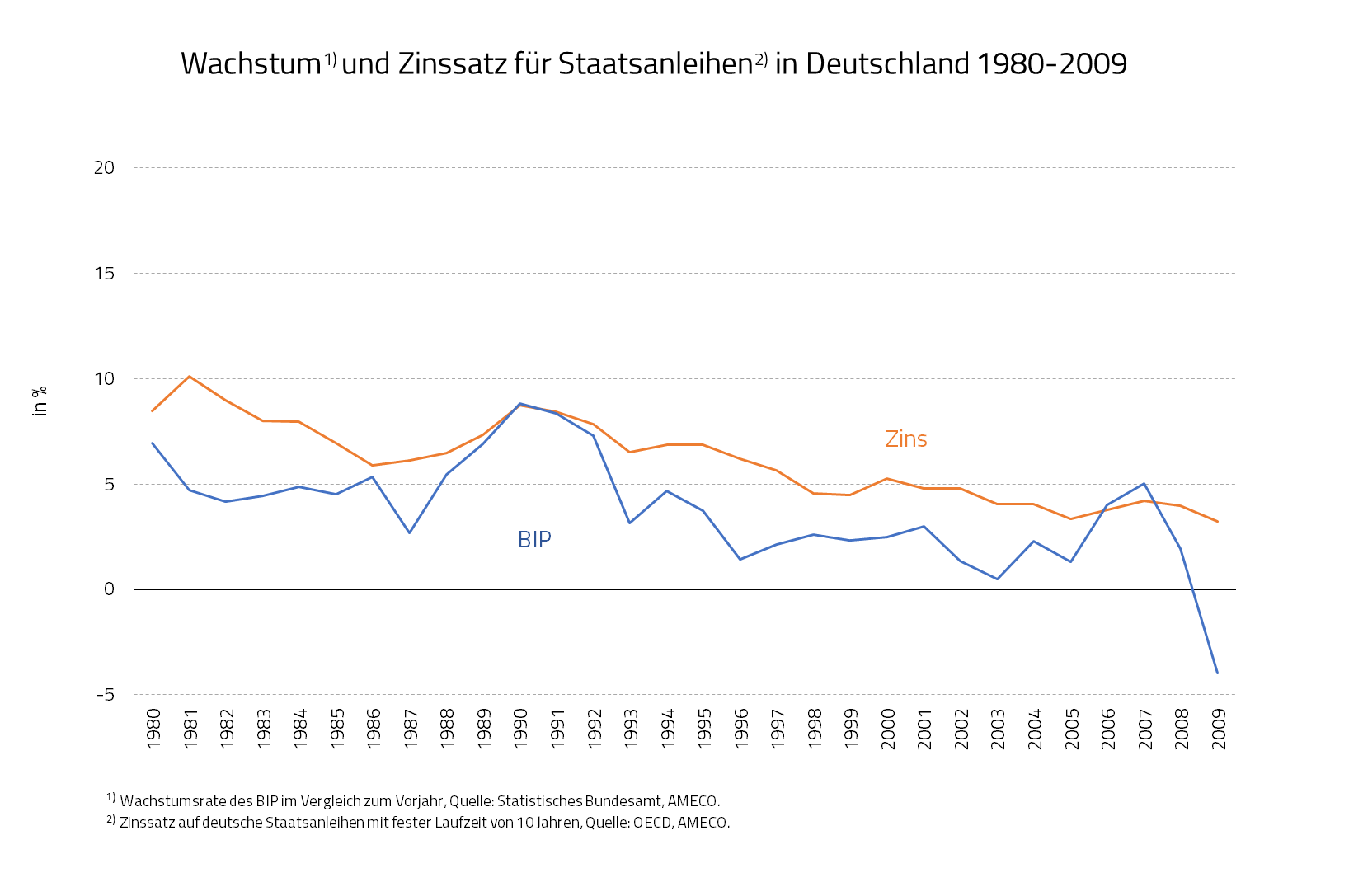

For the following decades, the conditions changed; one can also say that the market-economy was stood on its head. (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Growth and government bond yield in Germany 1980-2009

Apart from the years 1990 and 1991, the years of German unification (and a short episode in 2006 and 2007), the interest rate was always above the growth rate and thus, measured against “reasonable market conditions”, always too high. This applies in exactly the same way to France and Italy (Figures 4 and 5 as well as 6 and 7).

Figure 4

Growth and government bond yield in France 1960-1979

Figure 5

Growth and government bond yield in France 1980-2009

Figure 6

Growth and government bond yield in Italy 1960-1979

Figure 7

Growth and government bond yield in Italy 1980-2009

Particularly striking is the case of Italy, where in the first period there is no contact at all between the two curves and in the second only three short phases, where the interest rate was not higher than the growth rate, i.e. the two touch each other.

In the third of these articles you will read what the decisive reasons for these findings are and why the USA is not affected in the same way as Europe by the weakness in growth that this actually implies.