Capitalism is celebrated by the liberals as a success story. But this success can only be seen in the USA – and, even then, only for reasons that are incompatible with the liberals’ own ideology.

Originally posted in German at Makroskop

Translated and edited by BRAVE NEW EUROPE

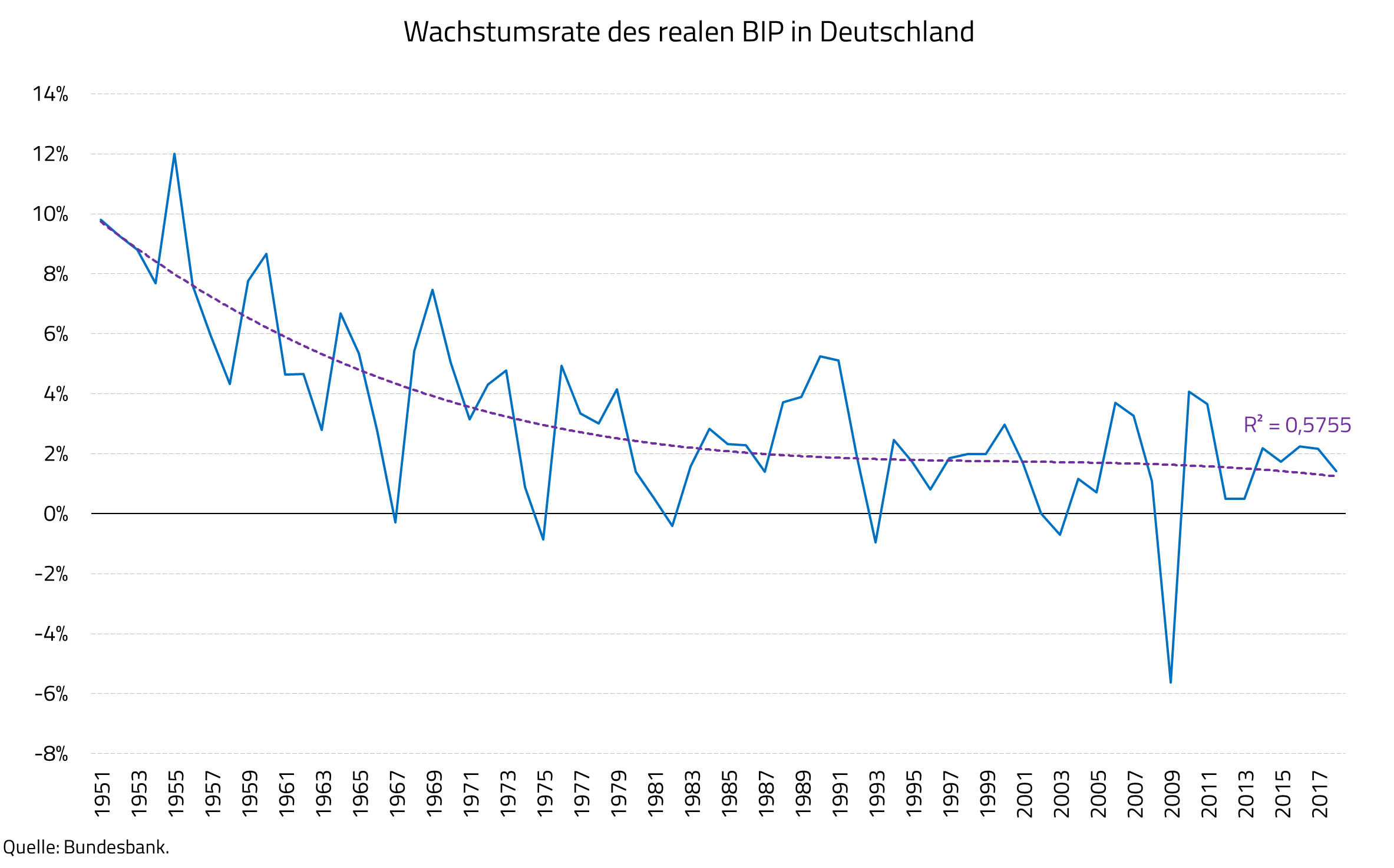

In the second part I already pointed out that the neo-liberal revolution in Germany after 1980 was by no means a success story. Real GDP growth has been declining throughout (Figure 1), a result that would have been much more pronounced had it not been for the enormous demand effects of German reunification, initiated by the state, which resulted in very high growth rates for several years.

Figure 1

Real GDP growth in Germany

After the start of European Monetary Union (EMU), it was the positive effects of German wage dumping that prevented an even stronger slowdown in the growth of economic output.

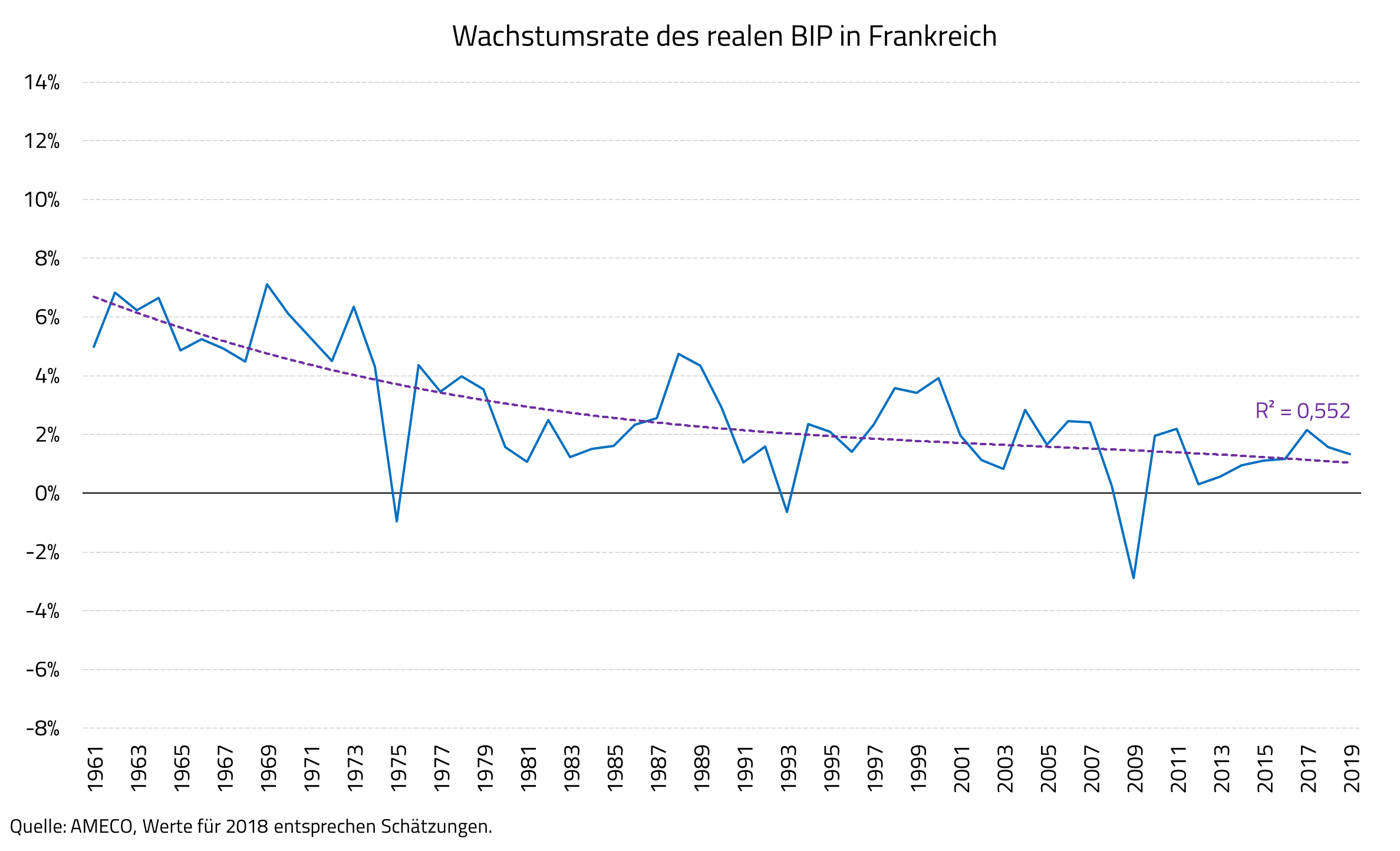

In France, these two positive effects did not occur, so the slowdown was much stronger. After the Great Recession of 2008/2009, the economy did not really recover and unemployment remained high.

Figure 2

Real GDP growth in France

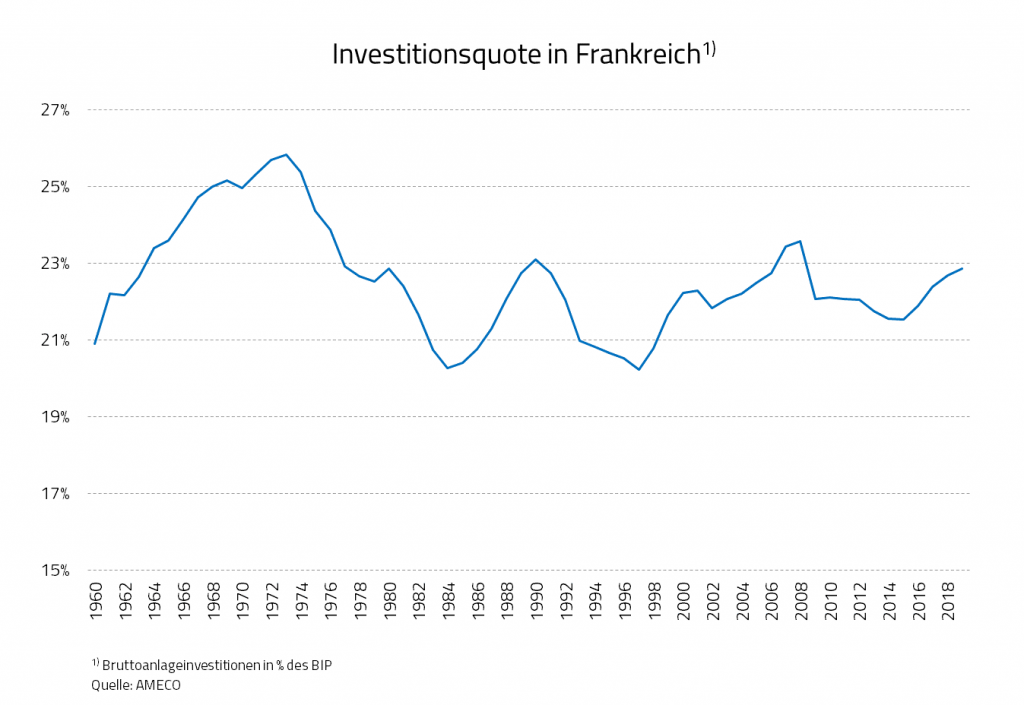

Weak investment dynamics

The investment ratio (total gross fixed capital formation) fell in France from 2008 to 2014 (Figure 3) and has recovered only slightly since then. It must be assumed that corporate investment has fared even worse, but unfortunately we do not have any comprehensible data on this.

Figure 3

Investment rate in France

Even more than France, Italy suffers from the domination of neo-liberalism, in particular the variant that prevails in EMU. Because Italy already has a high level of debt, the absurd rules of the Stability and Growth Pact force it to practice austerity against all reason. In other words, despite a lack of private investment and debt dynamics (at zero interest rates), Italy must refrain from government stimulus. As Figure 4 shows, the result is catastrophic.

Figure 4

Real GDP growth in Italy

The investment rate in Italy has reached a historically low level (Figure 5). And this is in a country that in the past was characterised by dynamic investment activity, especially in the industrial sector – more than almost any other.

Figure 5

Investment rate in Italy

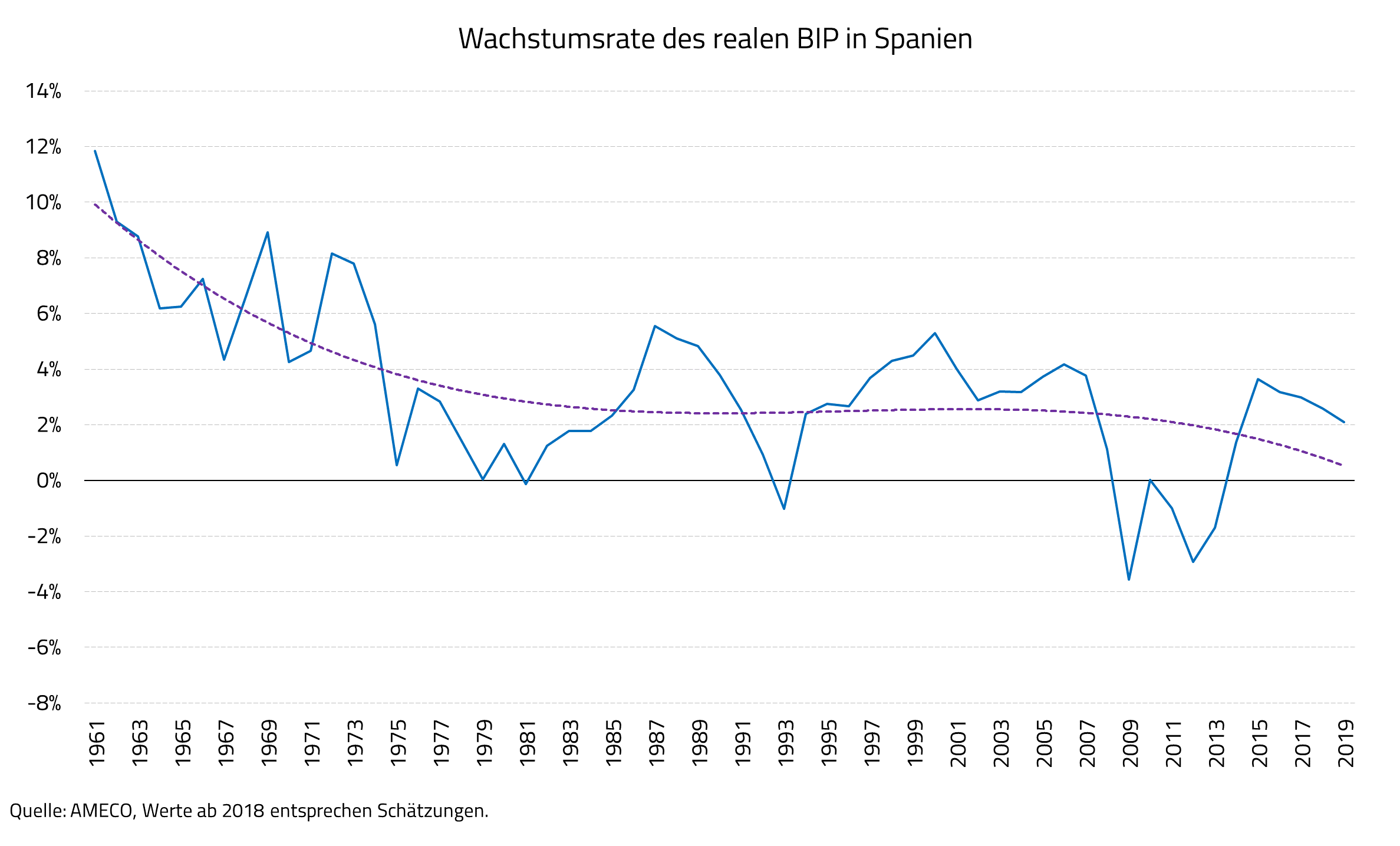

Less dramatic is the development in Spain, where the first years of EMU were accompanied by a pronounced housing construction boom, with correspondingly high GDP rates (Chart 6). However, if you take into account that recently there have been considerable doubts about the official calculation of Spain’s GDP, there is probably no better economic performance in evidence here.

Figure 6

Real GDP growth in Spain

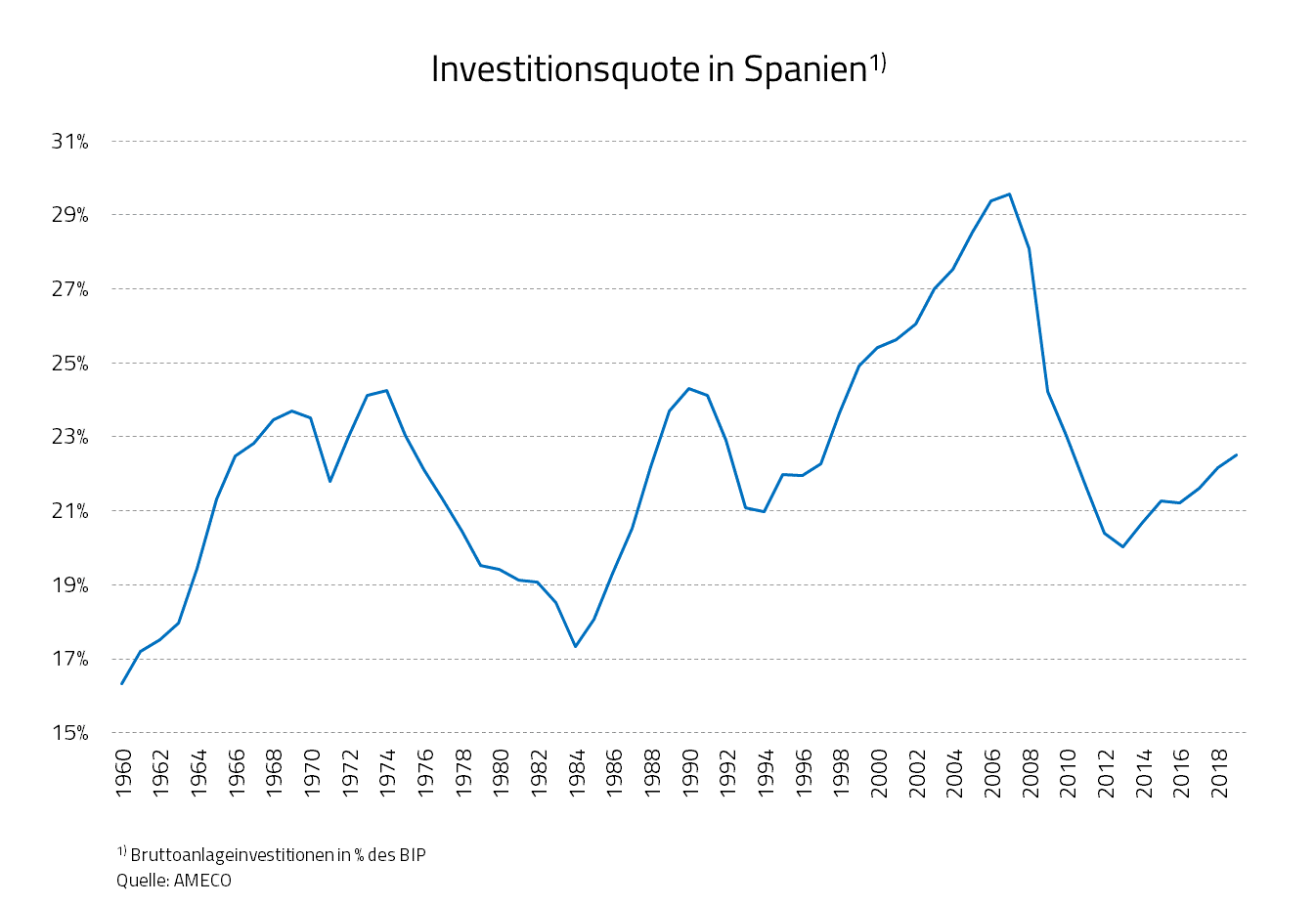

In Spain the investment rate was raised by the housing boom of the 2000s, but proved unsustainable (Figure 7). There was no real recovery after 2008/2009.

Figure 7

Investment rate in Spain

A country that falls slightly outside the above grid is Japan, where the boom lasted much longer, until the end of the 1980s. But in the end the boom was also fuelled by a grandiose and irrational real-estate bubble. Growth then collapsed and has not yet recovered (Figure 8). Growth rates of around one percent have been achieved only with the help of massive government intervention. At the same time, however, the employment situation in Japan is better than in all Western industrialised countries.

Figure 8

Real GDP growth in Japan

The investment rate, which had reached an enormous level of over 30 percent in the 1960s and 1980s, is now at the level of Western industrialised countries, and has barely risen since 2010 (Figure 9).

Figure 9

Investment rate in Japan

Is all this technological?

Now, many argue that the slowdown in growth is due not so much to the wrong economic policy as to a general trend of declining innovation in mature economies, from which ultimately no country can escape. This is proved, they say, by declining rates of labour productivity growth. It’s an assertion that can be made, but certainly cannot be proved.

What we see in the weakening of labour productivity growth rates is always a mixture of technological changes and the speed at which these innovations are implemented, i.e. converted into investment activity. Weak investment prevents high productivity growth even when the rates of development of technological innovations are high.

The big exception

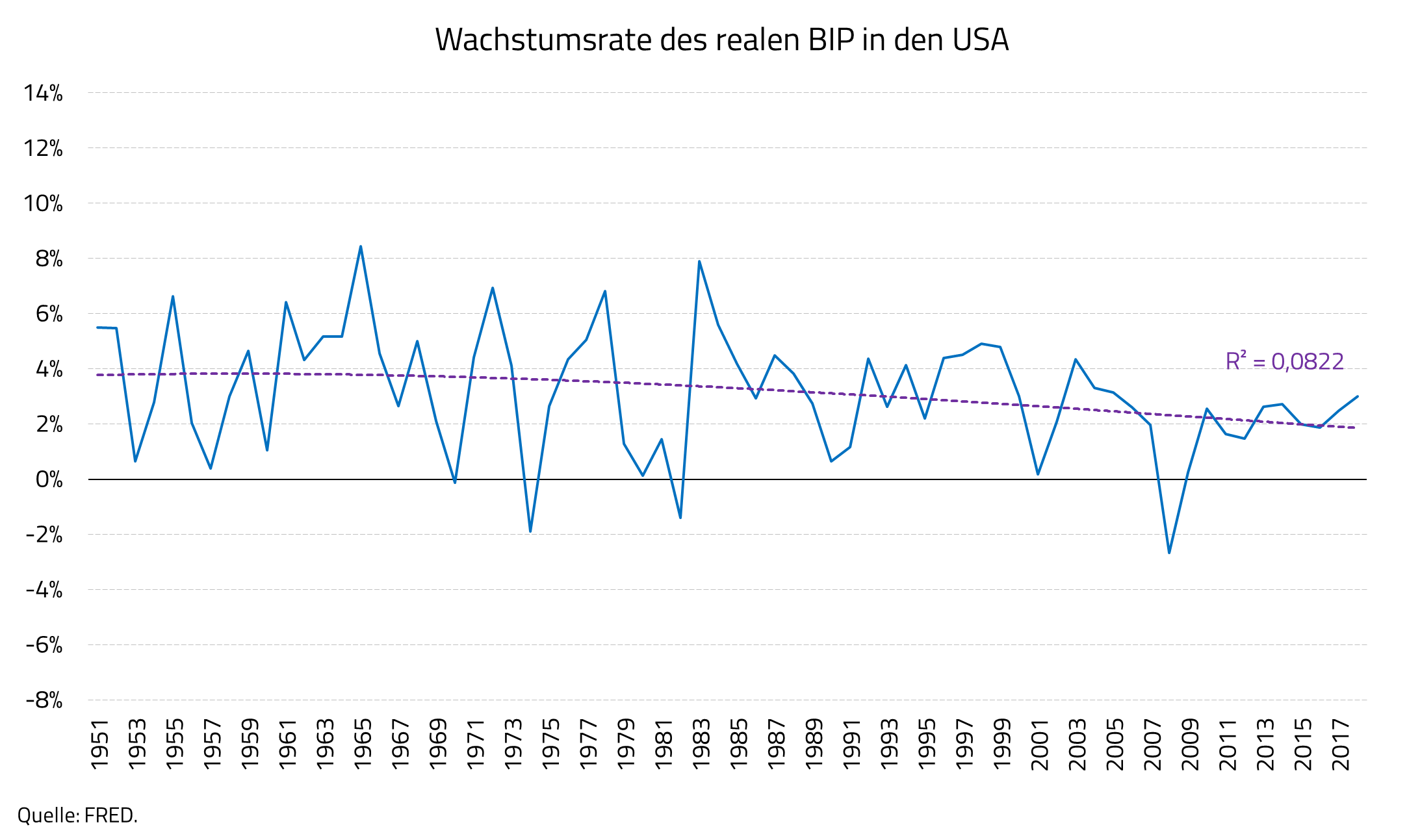

In order to refute the argument empirically, you need to find a “black swan”, i.e. a country in which conditions have become much less bad. And indeed, that country exists. The only large country in the Western world that has been able to escape this negative trend to a considerable extent is the USA. Here, too, growth momentum has slowed, but far less than in other countries (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Real GDP growth in the USA

The investment ratio in the USA has tended not to fall, and has recovered enormously since 2008/2009 (Figure 11). Although the large increase in the 2000s can clearly be attributed to an irrational real-estate boom, there is no simple explanation for the recovery since then.

Figure 11

Investment rate in the USA

If one adds that the USA has succeeded in reducing unemployment to a level that can be called full employment even in this cycle, one must seriously ask what the USA has done differently from the other countries. We have already given the answer a number of times when looking at fiscal balances: the USA has pursued a very pragmatic economic policy in an effort to bring unemployment close to full employment levels in every upturn.

As long as private market dynamics – driven by expansive monetary policy – were sufficient, the state held back. But this phase was already over in the mid-1970s. Then, without massive government stimulus from fiscal policy, there was only one return to full employment. Only during the phase of the so-called dotcom bubble in the second half of the 1990s, was the state able to get by again without any new indebtedness of its own. At that time private households increased their spending to such an extent that on balance they became indebted year after year and did not save (see Figure 12, where the breakdown, unlike in Figure 13, includes all state indebtedness).

Figure 12

Financial balance in the USA by economic sector as a percentage of nominal GDP

[Ausland = Overseas, Private Haushalte = Private households, Unternehmen = Companies, Staat = The state]

[Ausland = Overseas, Private Haushalte = Private households, Unternehmen = Companies, Staat = The state]

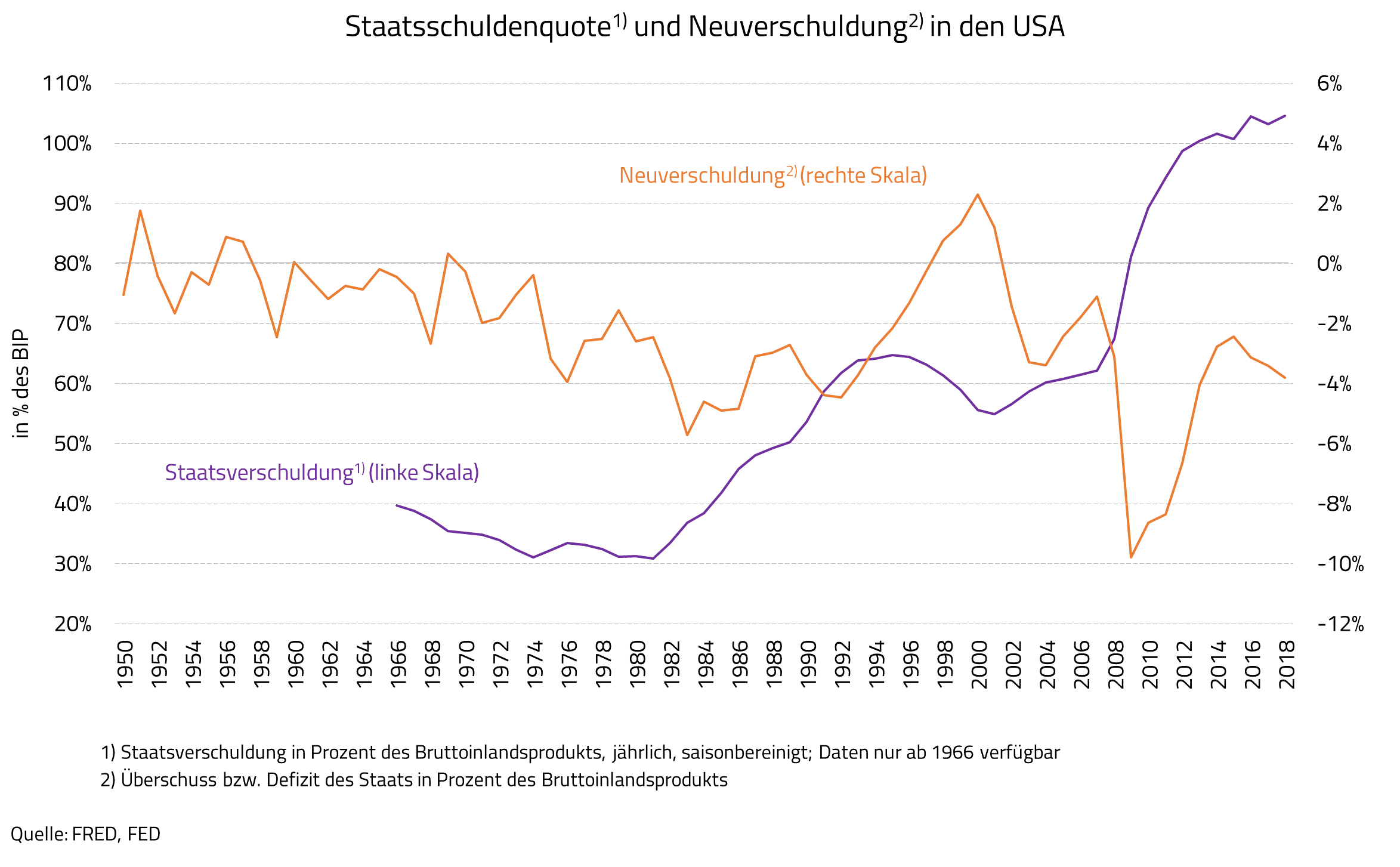

Subsequently, the companies saved again, i.e. spent less than they earned. Now, in the world’s largest market economy, there was no way for the state to rely on market forces. The gap between income and expenditure has been widening, and even now that full employment has been reached, the state is still increasing its deficit again. In the past fiscal year it was 3.9 percent of GDP or 700 billion US dollars (only for the central government). According to recent estimates, the absolute sum for this fiscal year (ending September 30th) will be in the order of $1,000 billion.

Figure 13

State debt and new indebtedness of the USA

[State indebtness as a percentage of GDP, seasonally adjusted (left-hand scale). Surplus or deficit as a percentage of GDP (right-hand scale)]

[State indebtness as a percentage of GDP, seasonally adjusted (left-hand scale). Surplus or deficit as a percentage of GDP (right-hand scale)]

Total debt (as a percentage of GDP, which we consider an inappropriate definition) will certainly rise towards 110 percent in 2019. Contrary to what the liberals and neo-liberals believe, this is not a problem. It shows, however, that there can be no reasonable economic development without a permanently greater financial commitment on the part of the state.

What follows?

In a world in which – via monetarism and neo-liberal labour market policy (“labour market flexibility”) – demand dynamics are systematically restricted, only the state can provide a remedy. Through its own aggressive demand policy, it can create a dynamic in the market economy that is sufficiently large to achieve ambitious employment goals. The United States has understood this and has developed an impressive pragmatism across both parties in terms of government debt. In Japan, too, the state has understood that companies that save and won’t invest are creating a completely new situation and are making the state directly and indispensably responsible for demand management.

The European Commission and the European Council, with their dogma of a “healthy” fiscal policy – driven largely by Germany – have left the ranks of rational governments behind. The result is persistently high unemployment. A changing of the guard at the Commission could have been an opportunity to get things moving. But even the first decision, on the election of the President of the Commission, is a step in the wrong direction. It is therefore inevitable that economic and social problems will increasingly call the entire European project into question, because the “populists” can point to the spectacular failure of economic policy.