These days, we are treated to an interesting spectacle. Although the ‘greedy beast’ called inflation met its demise in plain view quite some time ago, the flock of sheep continues to bleat as if nothing had happened. The fear of the sheep is fueled by the ‘experts’ who are paraded through the media every day, shaking their heads in concern: the beast could not be dead after all, it could just be sleeping, it could suddenly raise its head again in November or December and quickly gobble a few more sheep.

Although the rate of inflation in the euro area had already fallen below the ECB’s target of 2 per cent in September, the experts’ “concern” remains undiminished. They simply look at other rates to justify their concern. Since the so-called core rate is now also approaching 2 per cent, they have suddenly discovered the prices of services, which are still rising by 4 per cent. According to the relevant ‘bank economists’, this shows that inflation has not been defeated, but is still dormant in the system, mainly due to strong wage increases.

Crude inflation theories

Isabel Schnabel, the German member of the ECB’s Executive Board, has given particularly intensive thought to the dangers of renewed inflation. In an interview with the FAZ on 26 July this year, she said:

‘The crucial question, however, is whether the strong growth in wages is merely being driven by a process of real wage catch-up following the high rates of inflation in recent years, in order to compensate for the loss of purchasing power – or whether wages are rising so sharply in part because companies are having to pay higher wages due to the labour shortage.’

In the second case, they fear that inflation could rise again because rising wages would lead to rising prices. This would bring the ECB back into the picture.

What is remarkable about this analysis is, first of all, that it states that there is a catch-up process in real wages due to high inflation rates, but in the case of a labour shortage, its second case, it assumes that ‘wages’ will rise and inflation rates will follow, although one would expect real wages to rise when there is a labour shortage (at least in the neoclassical theory, which the ECB does not question). Consequently, nominal wages could well rise without prices following suit. Especially when it comes to a real labour shortage, in the ECB’s theoretical world the market should be able to find a solution in the form of rising real wages without the ECB having to intervene in practice.

Everything else that is still in the system is not a problem. Even if there are still some rearguard actions because of price increases in the past holding the service price increases a little higher, it is nevertheless perfectly clear that from now on the wage agreements will be negotiated again on the basis of an inflation rate of two percent. This removes any risk of new inflationary dangers arising from this side. Anyone who says otherwise is presumably a lobbyist (of a bank, for example) or one of the many ‘experts’ who are trying hard to justify their own erroneous forecasts regarding the duration and danger of ‘inflation’.

Incidentally, contrary to what Ms Schnabel believes, there is no shortage of labour in Europe. The ECB should also take note of the fact that unemployment figures are rising and the number of vacancies is falling in most countries as a direct result of the recession for which the ECB is responsible. Furthermore, the unemployment rate in the EMU is still as high as 6.5 per cent and thus far above the level at which one could really speak of a labour shortage (as shown in my new book).

Evidence-based monetary policy?

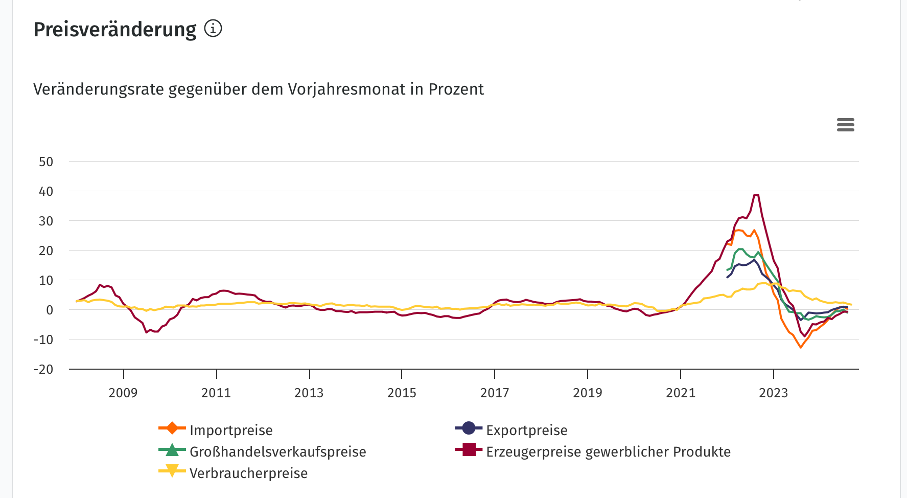

The ECB claims to follow an evidence-based approach. However, one wonders why it does not take note of the relevant evidence and does not even discuss it. Producer prices in industry (the dark red line) are, as the original image from the Federal Statistical Office for Germany shows, an excellent indicator for consumer prices (the orange line). Price increases at the consumer level have never occurred without producer prices having risen significantly beforehand.

However, the ECB removed producer prices from its list of indicators when it became clear at the end of 2022 that normalization at the producer level would occur extremely quickly and would challenge its scenario of complicated and prolonged inflation.

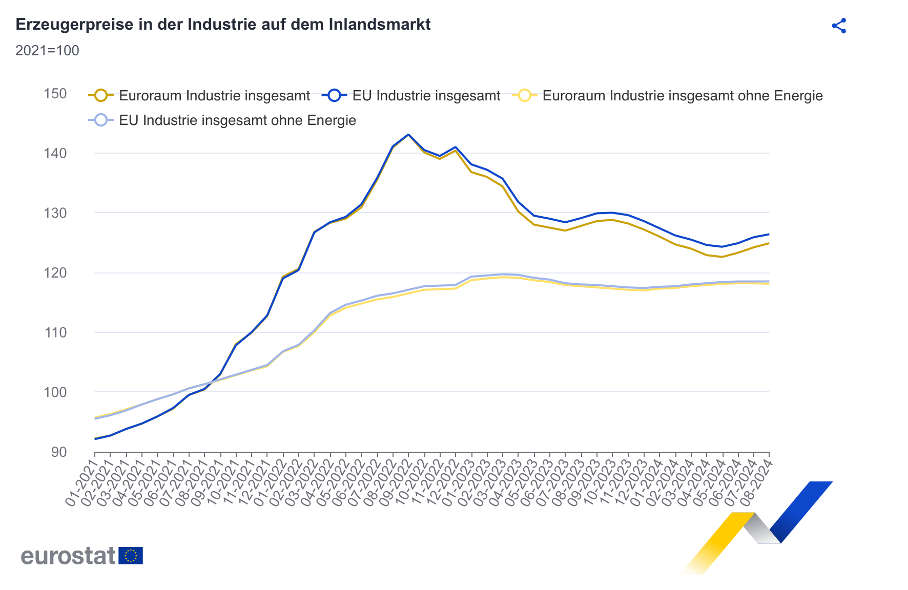

The latest producer price figures for the euro area published by Eurostat (can be found here) clearly show that there is no longer any risk of inflation for the EMU (original image below in German). Unlike the image above, this image shows an index, i.e. the level of development, rather than a growth rate.

While producer prices including energy have fallen in absolute terms, albeit with fluctuations, a value of 119 was reached for producer prices excluding energy (the light blue curve) as early as February 2023, i.e. 2 ½ years ago, and has never been exceeded since. There is an impressively steady horizontal development, i.e. an absolutely stable price level. There can be no doubt that this long-lasting price stability is the best indicator that, at the consumer level, too, apart from a few irregular fluctuations, nothing is happening that could jeopardise price stability.

Why is the US in a different league?

Yesterday, the US inflation rate of 2.4 per cent in September 2024 was published. There, too, the price increases of the past two years were only an episode. Now the situation there has normalized as well. The remarkable thing is that the normalization has been achieved without any recession at all. Growth rates are still positive, and the labour market situation is excellent. At just over 4 per cent, the unemployment rate is very close to the levels that have historically and currently signified full employment in the US. (Nominal) wages are rising by 4 to 5 per cent per year on average across the country, which definitely does not pose a risk of inflation.

The ECB and other experts should be urgently asking themselves how this can be. After all, they had convinced Europe that a recession and rising unemployment were needed to avert the risk of inflation. And in the US, the rate of inflation is falling at the same pace without a recession and with full employment? Just imagine if, in Europe, the state had thwarted the ECB’s plan to fight ‘inflation’ with the help of a recession, as happened in the US, by pursuing an extremely expansionary fiscal policy. What would the ECB have done? Would it have stepped up the restriction by another three gears to force the recession? Or would it have left it at slight interest rate increases, as the US Federal Reserve (Fed) did, which ultimately did little harm to the economy? More importantly, would the ECB now not insist on continuing to tighten monetary policy even with full employment and still high growth rates, while the Fed calmly lowers interest rates just as quickly as the ECB?

The answers are clear and show that Europe has an unsuitable monetary order and unsuitable monetary policymakers. Focusing monetary policy in Europe solely on price stability is inappropriate (as shown here). As in the US, monetary policy needs a mandate that targets economic development and unemployment.

Precisely because the ECB is independent and has such a unpretentious mandate, its policy should at least be heavily criticized in public and among economists. However, this is not the case. Almost everyone who knows anything about the matter behaves tame and the media are happy to parrot what the tame ‘experts’ and the ECB members themselves say. Those who hold the power of the media do not have to face the facts. And if you ignore the facts, not even fact-checkers can determine that you are systematically misleading the public.