(This is an automated translation, I corrected substantive mistakes but not grammar and style)

Cross-posted from Makroskop

In the corona discussion, many people feel that it is hopeless from the outset to search for a hypothesis that provides clear indications of the further course of the pandemic. But fortunately, the matter is not that simple.

If you look at the discussion about the so-called second wave, it seems as if you are facing a chaotic infection process that follows no rules whatsoever and can therefore only be controlled by pulling the emergency brake called lockdown from time to time. Once the emergency brake is pulled and the numbers go down, one can conclude without further ado that the political measures have been successful and is getting ready for the next mission.

This is how “the miracle of Madrid”, as it has been called in the press, comes about, namely the fact that after a sharp increase, the infection figures also drop very quickly. In Switzerland, the canton of Geneva, in particular, is admired for its rapidly declining numbers, even though it was considered a hotspot not long ago.

Almost no one asks whether there is perhaps an endogenous dynamic of the infection process that is responsible for such courses of events. Perhaps the numbers are declining precisely because they have risen sharply before and not although they have risen sharply. The recovery would then not be a miracle, but the result of the previous development. And more than that, shouldn’t we assume that there is a connection between the first wave and the second? If that is true, then politically significant conclusions could be drawn.

What is the appropriate indicator?

A major problem in diagnosing the situation is to find a suitable indicator. Currently, everyone is looking again at case numbers, i.e. the number of newly reported infections per day or per week. The problem with the case numbers, however, is the low comparability over time, i.e. from spring until today. Today it is clear that the case numbers published in spring must have been much too low, i.e. the number of unreported cases was high.

If the spring case numbers were to correctly reflect the actual number of infected persons, it would have to be stated that the mortality of Covid-19 has now fallen significantly. In almost all countries, the case numbers are many times higher than in spring, but the death rates are significantly lower in relation to the case numbers. This could mean that the virus has mutated and is much more harmless today than it was in spring, or that we are now much better able to deal with it in the health care system. Both would be good news, but nothing is known about mutations, and seen over so many countries, a dramatic improvement in the chances of cure in such a short time does not seem particularly plausible.

It is much more likely that the case numbers that were identified in spring were much too low because there were many cases without symptoms and many people with mild symptoms who did not go to the doctor in the first place. If the mortality rate were the same as it is today, one would have to assume a case number in the region of 200,000 per day for France, as some estimates actually suggest. If one does not want to rely on such estimates, one has to look for other indicators.

An alternative to the case numbers are the deaths attributed to the disease Covid-19. But here, too, there are considerable concerns about the meaningfulness of these figures. First, there is no reliable international comparability because the definition of what it means to “have died of Covid-19” is handled differently from country to country. Secondly, when looking at the number of deaths in a country, it must be noted that many patients whose death is attributed to Covid-19 would have died for other reasons without the virus. The absolute number of deaths does not indicate the specific corona problem.

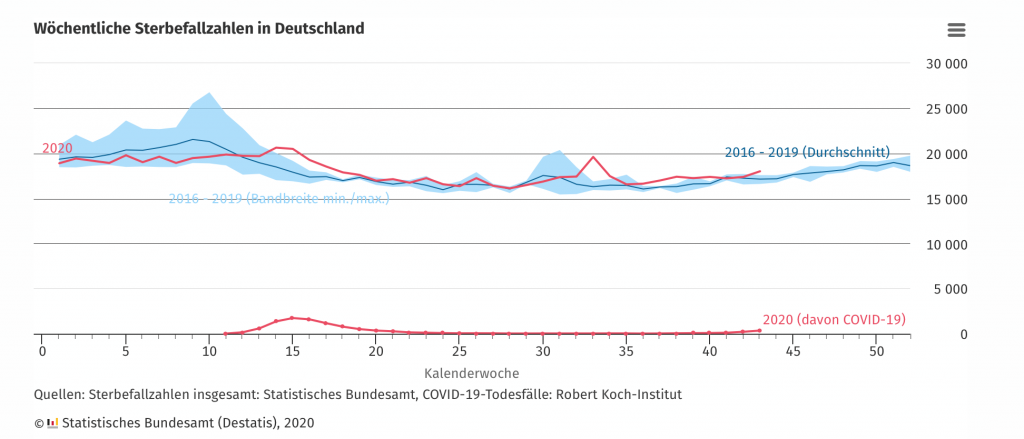

Both problems can be avoided by looking at mortality over time. If many more people have died in a year at the time the corona virus appeared than in previous years, there is a strong indication for an effect of corona, as Figure 1 shows. The data come from a special evaluation of the Federal Statistical Office in Germany. It seems that with all our medical precautions we cannot prevent between 15,000 and 20,000 people from dying in Germany every week, depending on the season.

Figure 1

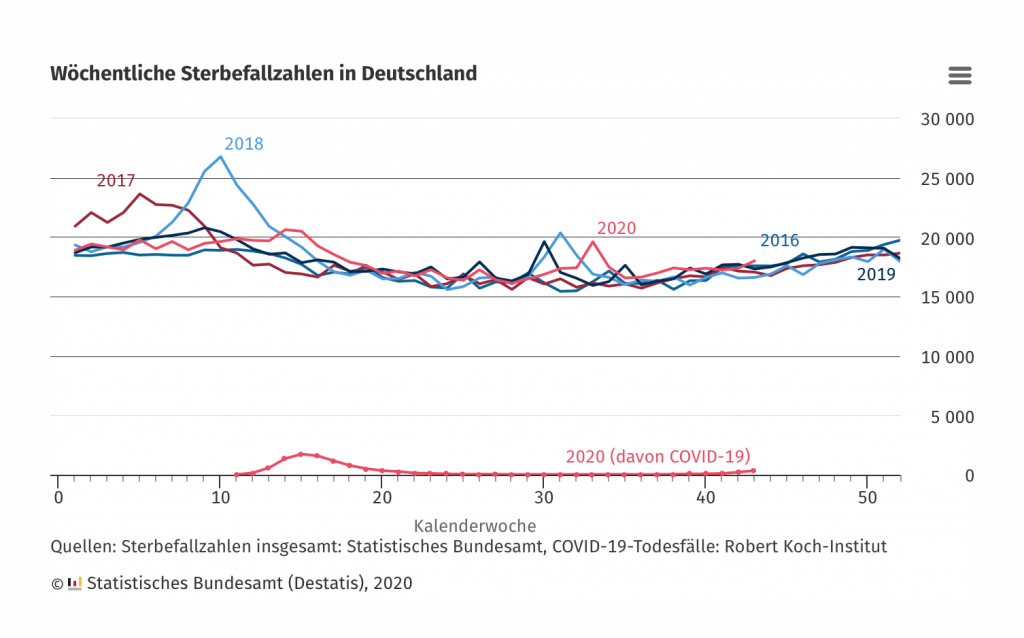

As the red curve shows, there was an upward deviation of mortality in spring with the appearance of Covid-19 from the 2016-2019 average (such deviations are often referred to as “excess mortality”). However, the figure also shows that this deviation was still within the fluctuation range of that (the blue area) which had occurred in the three previous years in terms of seasonal fluctuations. Figure 2 again explicitly shows the death figures for the past four years (2020 of course incomplete), and it can be seen that it was mainly in 2018, around the tenth week, that a high mortality rate was observed, which obviously has to be attributed to a seasonal influence.

Figure 2

Mortality as an indicator is also relevant because the repeatedly cited hospital overload is not independent of it. It is difficult to imagine that a country will be generally overburdened with hospitals if the mortality figures do not exceed the level of previous years. However, this does not rule out the possibility of regional bottlenecks.

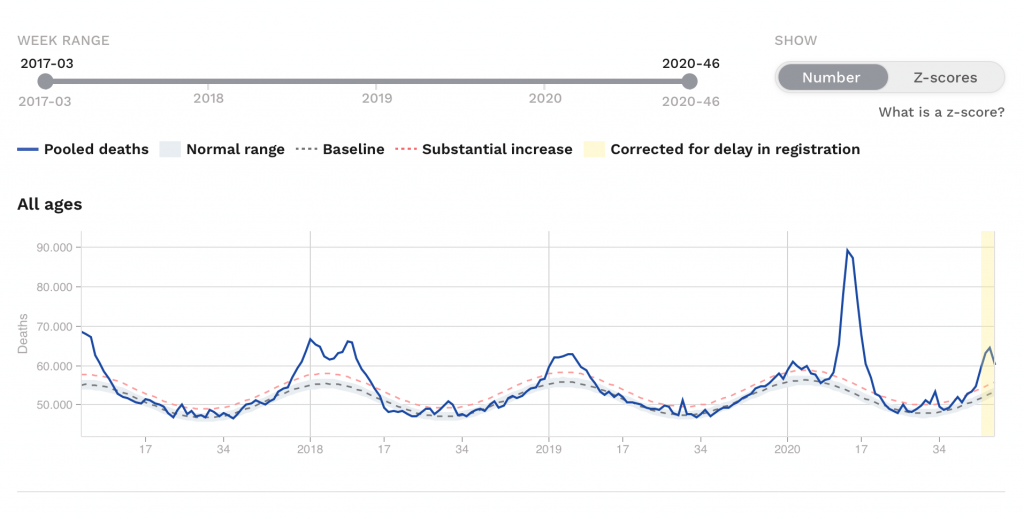

For Europe, at least for 26 countries, there are data compiled by Euromomo (the figures in Figure 3 reflect the situation as of November 24). As Figure 3 shows, these countries taken together clearly have an excessively high mortality rate in the two months of the first wave of corona infections. It goes considerably beyond the seasonal patterns that have occurred in previous years, mostly in winter. In the critical weeks of March 2020, some 20,000 more people died in these countries than on previous occasions such as 2017, when there was a major wave of influenza in Europe. This is undoubtedly a finding that must not be belittled in political debate.

Figure 3

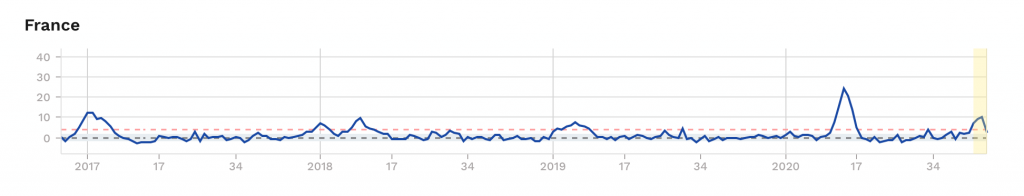

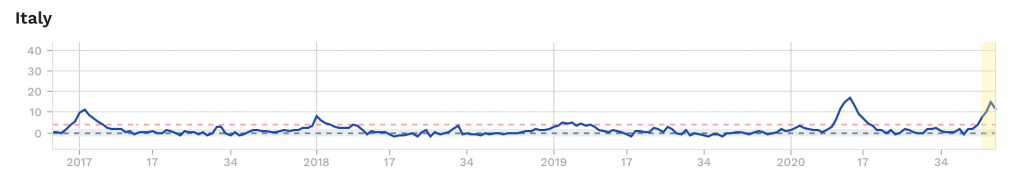

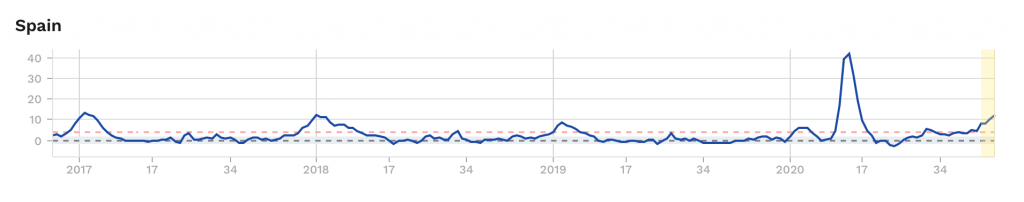

Looking at the countries most affected, it is noticeable that among the large countries Italy, France and Spain had a particularly high mortality rate in spring 2020 (Figures 4 to 6).

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

In Spain alone, the number of deaths in March and April 2020 peaked at 30,000 higher than the peak recorded so far in the winter of 2017. In these three countries, there is a striking seasonal pattern compared to other countries; almost every winter there is a significant increase in the number of deaths when compared to the average over several years. But England also had a truly exceptional peak (not shown here), without similarly strong seasonal fluctuations in the years before. In many other countries, such as Norway, Hungary and Greece, no abnormalities at all were observed in spring 2020. Still others, such as Sweden and Switzerland, show significantly higher mortality this spring, whereas in the years before they had hardly any seasonal effects.

A high mortality rate that occurs suddenly, as in the three southern European countries, is of course very quickly accompanied by an overload of the health care system, because this is at best based on the normal seasonal pattern, i.e. an increase in the number of illnesses in the previous winter, although, as mentioned above, in the southern European countries the seasonal burden in autumn and spring was already particularly high in earlier years.

An endogenous rhythm?

For the whole of Europe, as Figure 3 clearly shows, there is a pronounced seasonality in the curves. Although the effects of Covid-19 only set in relatively late in the season of last spring, they fit in perfectly with the seasonal pattern. In 2018, too, there were seasonal influences that caused the death rates to rise only relatively late in the winter. With the beginning of autumn this year, case numbers increased again, but this time, as far as can be seen from the current situation, at a pace not much greater than in 2018 and also 2019 in autumn. Most recently, they have been declining slightly again.

The crucial question remains: Where does the seasonality come from and what role does it play for the future course of the curves. We also have to ask what significance the various lockdowns have, which were imposed whenever rising curves became apparent. Even without having a great deal of knowledge about viruses, it can be deduced from the curves that the corona virus (like the other viruses responsible for most of the “events” observed during the winter season) apparently finds favorable conditions for its multiplication in the transitional season from summer to winter and from winter to summer. This is why the words “flu wave” and “flu season” have become part of our everyday language.

It is also clear that every wave favored by the season breaks. Yes, it breaks because it is its inner logic to break. With the initially exponential growth, it cannot continue at will, because the virus finds fewer and fewer people who are not yet infected as time goes by, and because after some time “its season” has literally expired. In the case of a seasonally occurring disease, however, it must be remembered that the course of the different seasonal courses is not isolated from each other.

The central question is whether the next wave will break out of itself in time to avoid overburdening the health care systems. When the virus first appears, this is by no means certain, and politicians are acting with great uncertainty. However, the second seasonal wave can and must be based on the first one. After all, despite all the precautions that were in force throughout the summer in Europe (such as wearing a mask on many occasions, keeping a distance and banning mass events), the virus found favorable conditions again in autumn, allowing it to multiply throughout Europe.

In one respect, however, the conditions for the virus in autumn were considerably less favorable: many millions of people in Europe were already infected in spring and built up an immunity that blocked the virus’s path (recent American studies have just given strong indications that the immunity is stable and lasts for some time). However, in order to estimate the quantitative significance of this effect, one must not simply compare the number of people infected with the total population. The first to build up immunity were probably those who were exposed because of their way of working and living and thus could not (or did not want to) avoid contact with the virus. The millions of citizens who have so far avoided the virus because of their way of life and continue to do so, do not play a role in this calculation.

Consequently, everything suggests that the second wave will be smaller than the first and not, as Angela Merkel and many others believe, bigger. Of course, it cannot be completely ruled out that in some regions the second wave will be bigger because the region was spared by special circumstances during the first one. For a large and, in terms of climate, relatively homogeneous entity such as Northern Europe, this is very unlikely and the Euromomo results shown above (Figure 3) undoubtedly point to such a result.

But can politics alone build on such a logic? Nobody can say that with one hundred percent certainty. But it can be said with one hundred percent certainty that it is precisely this logic that everyone, including politicians, is counting on for a successful vaccination in the near future. After all, vaccination is nothing more than the immunization of larger parts of the population. If one hopes for this, one must also acknowledge that the first wave, which hit a completely unprepared population and was apparently very large, immunized parts of the population, so that the second wave, which was triggered by the usual seasonal conditions, will not become as large as the first. The third wave, in which the vaccination should then already play a role, will be even smaller.

It is no art to predict that the peak of this winter, which has already passed in many countries, will remain well below the peak of spring. In France, for example, the second wave has now clearly passed its peak. All indicators are clearly pointing downwards. Mortality was again increased, but the values remained well below those of spring. Even Belgium, which was heavily affected, is without doubt “over the top”; here too, with a lower “excess mortality” than in spring. The same applies to Spain. Given the comparable trends that can be expected in the other countries, the health care system is likely to be overloaded at most in a few regional hotspots, but in no case for Europe as a whole and probably not for any individual country as a whole.

The role of politics

The question remains what the lockdowns mean in all this. Lockdowns are an attempt to keep parts of the population away from the virus in order to avoid temporarily overburdening the health care systems. This may well be appropriate in a situation such as in spring, when there is great uncertainty about the characteristics of the virus. It is accepted that fewer people will become immune to the virus, which makes the second wave, which nowhere except China has been able to avoid, larger than it would otherwise have been (but it still remains smaller than the first).

The problem with the quantitative classification of the lockdown is that its effects coincide with the breaking of the wave, which is to be expected anyway, because politicians prescribe strict measures in the exponential phase, because then they see that the number of deaths or people admitted to intensive care units with Covid-19 increases. However, the need to use lockdowns decreases with each wave and is particularly low when, even in the first wave, hospitals were not overloaded and mortality did not rise noticeably.

The above analysis, to make this clear, has absolutely nothing to do with the concept of herd immunity. Anyone who, like me, advises to include seasonal patterns in the political considerations does not in any way suggest that there are no political options to avoid temporary overloading of hospitals anyway, so everything has to be left running.

However, herd immunity is also formed in the way that from season to season, larger and larger parts of the population are infected. In no way would the entire population be infected at once, as is sometimes painted on the wall in horror scenarios. It always remains at a seasonal rhythm. However, the concept of herd immunity is associated with a high degree of uncertainty at the first appearance of the virus and politics, as worldwide experience has shown, cannot simply rely on it.

In summary, the picture is quite clear. Covid-19 is a very serious disease and it is in any case justified to warn the population on the part of politicians and to give certain recommendations for behavior. In the first phase in spring 2020, with great uncertainty about the effects of the virus, drastic measures were also justifiable.

In the meantime, however, enough facts should be known nationally and internationally to gain a better understanding of the dynamics of the infection process even without the unreliable case numbers. Greater serenity on the part of politicians is called for, even though, to emphasize it once again, it is undeniable that Covid-19 is a very serious disease.