In Germany and other European countries, fossil fuel prices have been the focus of political discussion for several weeks. Most are moaning about the rise in prices. Some politicians even want to reverse or at least mitigate it. Markus Söder (CSU) and Dietmar Bartsch (Die Linke), for example, have formed an unexpected coalition on this issue: While the former told Bild am Sonntag on Oct. 31, “We have to accommodate citizens fiscally in these difficult times … A reduced VAT rate on energy and fuels would relieve citizens of the worst hardships,” the latter went on record with Redaktionsnetzwerk Deutschland a day later, saying, “The planned 20 percent increase in the CO2 price from January should be canceled and the entire market model put to the test in light of the price explosion.”

To distinguish populist demands from considerations that make sense in terms of realpolitik, one has to look at the longer-term development of fossil fuel prices. Looking back a few months is not enough to make an assessment. And one must ask how prices have changed relative to citizens’ incomes over the past several decades.

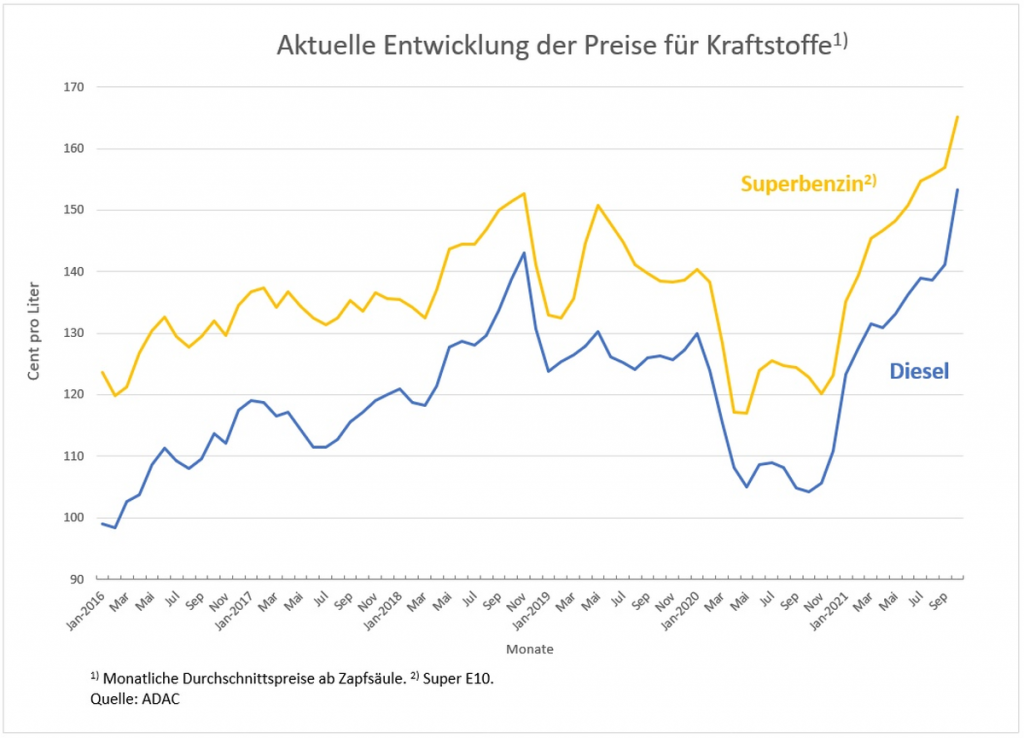

Figure 1

Figure 1 shows the prices per liter of Super E10 and diesel paid at the pump on a monthly average over the past six years. The first thing that jumps out is the drop in prices at the start of the Corona crisis and the sharp rise in prices for both types of fuel since the end of 2020: while people were still paying around 140 cents per liter of super gasoline and 130 cents per liter of diesel at the pump in January 2020, prices fell to 117 cents for super in May 2020 and to 104 cents for diesel in October 2020. Since then, however, prices have risen steeply again. Most recently, they were around 165 and 153 cents, respectively. However, it is easy to forget that, as Figure 2 shows, there was already a period when fuel prices increased at a similar pace and reached the same magnitude.

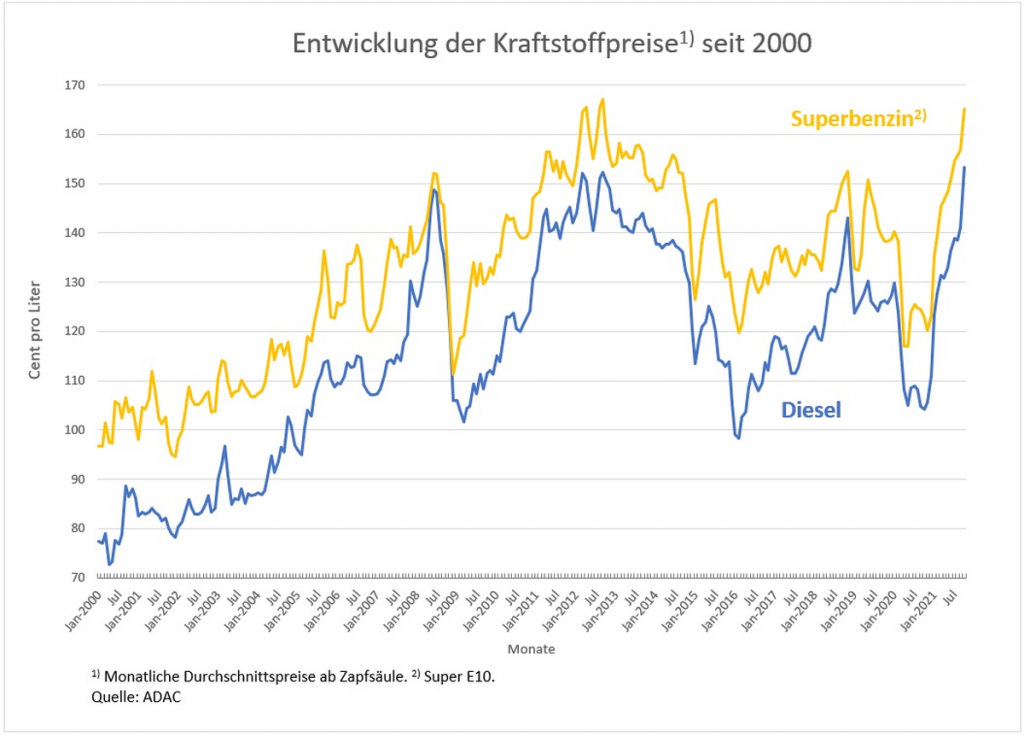

Figure 2

In late summer 2012, prices peaked at 167 (super) and 152 (diesel) cents per liter. During the speculation-driven commodity price rally in the early 2000s, crude oil had become almost universally more expensive and consequently so had filling up at the pump. As in other commodity markets, the price bubble in the oil market had already burst in the course of the financial crisis of 2008/2009, but it built up again in the following three years. This was followed by years of sharp price declines, which are now being hastily used as a benchmark to prove the “excessive” burden on those driving and heating with fossil fuels.

The government could reduce its taxes and duties levied on fossil fuels to depress market price trends. In the case of premium gasoline, the energy tax, the petroleum stockpiling levy and the CO2 tax together accounted for more than 50 percent of the gross price in 2020; including VAT, almost two-thirds of the final price even went to the state. For diesel, the burden was around ten percentage points lower, i.e. still well over half of the final price if VAT is included. Currently, however, this percentage is somewhat lower for both types of fuel, since the levies (apart from VAT) are based on the quantity and not on the price of the fuel filled up.

Does the state have to act?

One argument against lowering government revenues on fossil fuels, however, is that there is an increasingly urgent search for solutions to save fossil fuels in order to curb global warming. Such solutions can only be expected in the context of a market economy if fossil fuels become continuously more expensive relative to other goods and to average incomes, i.e., if their prices rise in real terms. What has been the real development of prices for super and diesel in recent decades?

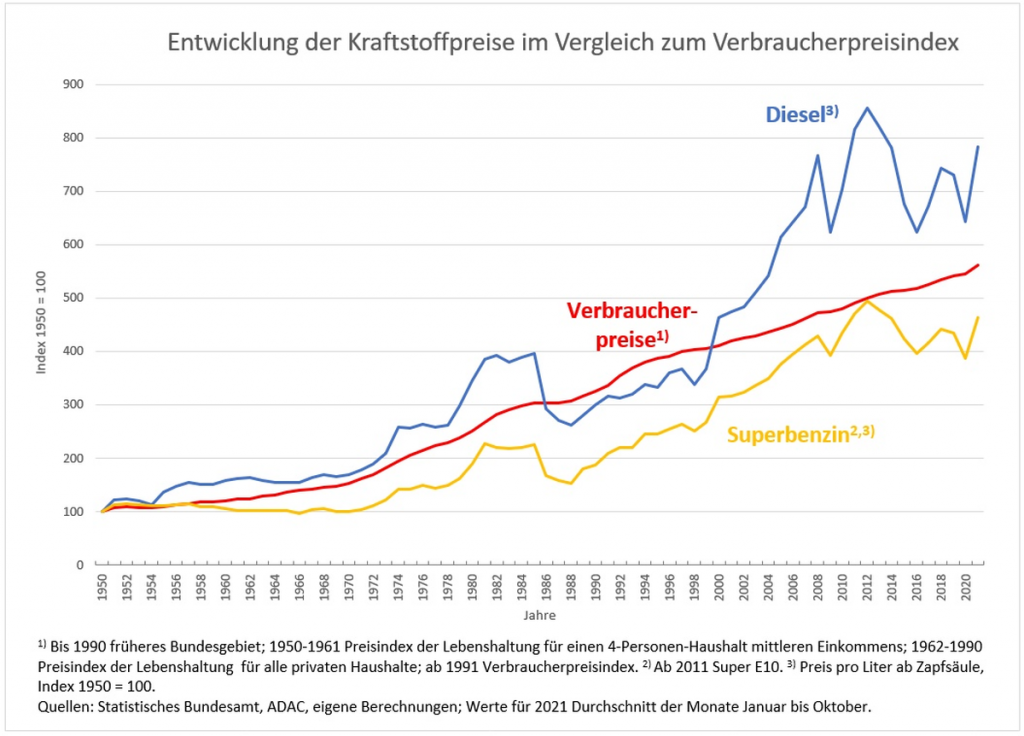

Figure 3 shows the development of fuel prices from 1950 onward in relation to the development of average consumer prices. Surprisingly, the price of premium gasoline has underperformed over the decades, with only that of diesel rising faster than other consumer prices most of the time. Both time series also show much larger fluctuations than consumer prices as a whole. It is noteworthy that the price surges in the two oil price crises in the mid- and late 1970s, commonly called “oil price explosions,” look rather moderate compared with the development in the 2000s up to the financial crisis.

Figure 3

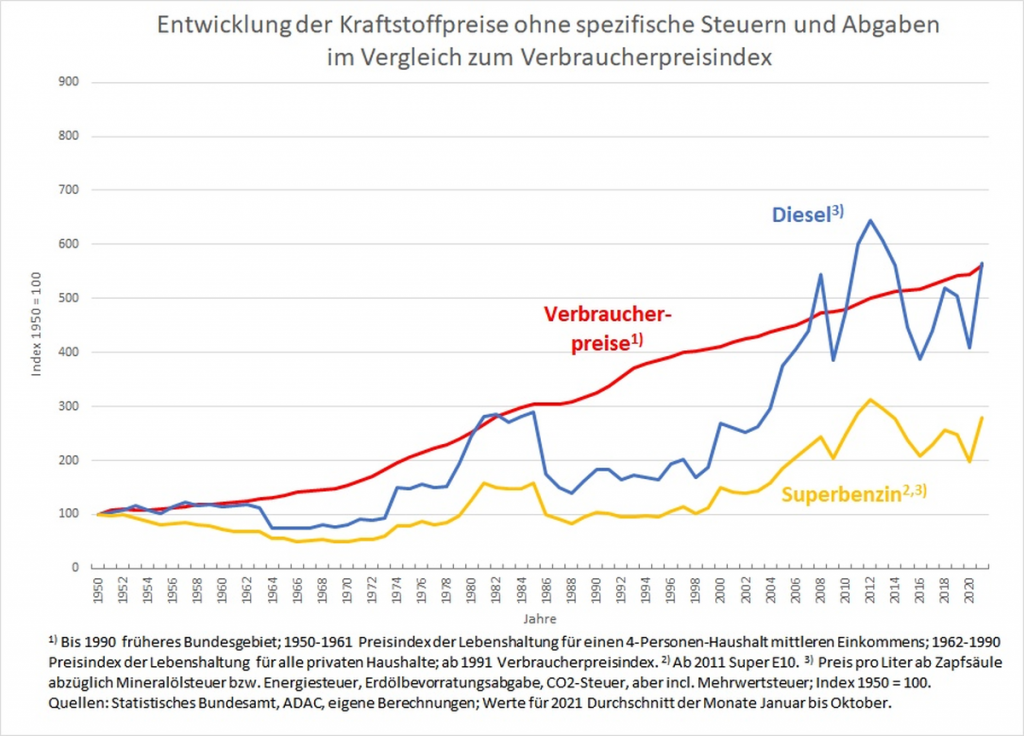

If fuel prices are adjusted for the energy tax (formerly mineral oil tax) and the other levies that have changed over the decades, but without factoring out the value-added tax, it becomes apparent how much the state has corrected upward the overall market price trend, which was strongly below average despite all the fluctuations (see figure 4): Without the state’s intervention, price indices would have lagged behind the general price trend for decades. This is consistently true for premium gasoline and, with the exception of a few years around the financial crisis, also for diesel. In other words, without the specific levies, driving with fossil fuels in Germany would have been much cheaper all these years.

Figure 4

Are citizens being overcharged?

However, in order to assess how much the oil and gasoline bill, including the government levies due, has really burdened the citizen, one must take into account the increased prosperity. The average citizen can afford many more goods today than 20 years ago, and even more so than 60 or even 70 years ago. The increase in the price level has gone hand in hand with a real development that has brought with it more, qualitatively better and completely new goods and production methods thanks to a much larger capital stock and thus much higher labor productivity.

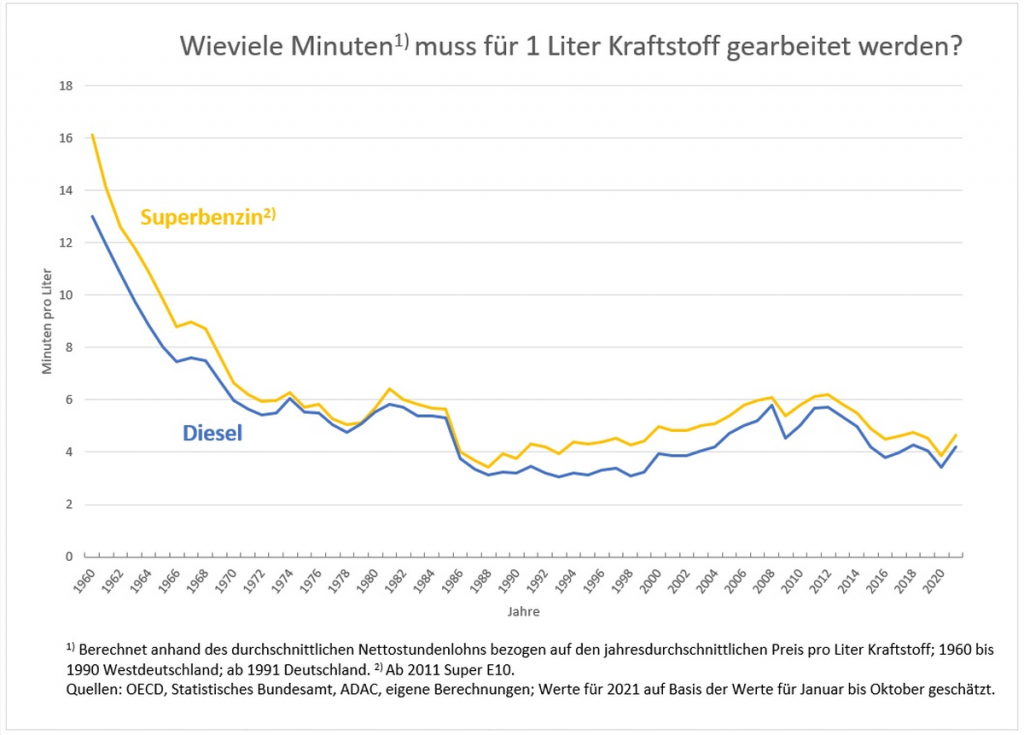

Old-fashioned goods, which include fossil fuels for motor vehicles, have become much more affordable as a result of this development. Figure 5 shows that it now takes significantly less labor time than in the past to earn the money for the same amount of fuel.

Figure 5

In 1960, employees had to work an average of 16 minutes to earn the equivalent of one liter of premium gasoline (the equivalent of 34.2 cents). For a liter of diesel, they needed 13 minutes of work time. In the 1950s, fuels were significantly more expensive, and the working time required was correspondingly longer. The prices of both fuels at the pump converged until the early 1970s, so that the working time required to pay for them also converged. This did not change again until the late 1980s, when the net price of and taxes on gasoline rose faster than on diesel.

Prior to the first oil price crisis, only about six minutes of labor time was required for one liter of fuel. This level was nearly halved by the 1990s, when between three and four minutes of average paid labor time was enough to purchase a liter of fuel, despite the two oil price crises in the mid- and late 1970s, which, after all, caused the price of crude oil to skyrocket. The increase in the 2000s, which briefly returned to the 6-minute level, was followed by another decline to well below five minutes. Even the current increase through October 2021 does not change the finding: measured in labor time, fuel is cheaper today than it was at the time of the oil price crises. On average over the past 40 years, it has been below the five-minute mark. Those who complain about high prices at the pump today are complaining at a low level.

If we also consider that the efficiency of internal combustion engines and consumption-related details of passenger car technology have increased enormously since the 1950s (data on diesel-powered industrial engines show that it increased by a quarter between 1952 and 2015), meaning that today you can travel more kilometers on one liter of fuel with the same weight of vehicle than 40 years ago, the price of fossil-fueled mobility has fallen even more than shown in Figure 5. The fact that many vehicle manufacturers and consumers have put this technical efficiency gain into higher horsepower figures and more luxurious equipment for their cars does not detract from this finding. All this means is that, from the point of view of the driver who is interested in comfort, a journey of the same length made on diesel or gasoline has become cheaper.

Price signals necessary for the ecological transformation of the economy, …

Against the background of this empirical finding, demands such as those cited at the beginning of this article to reduce the state’s share of the final price for super or diesel at the pump are incompatible with any market-based strategy for combating climate change. The curbing of fossil fuel consumption, if it is to be achieved by market mechanisms and not primarily by bans, needs a clear signal from the price side. Fossil fuels will only be substituted by climate-neutral energy sources if their price rises sharply and permanently compared with other goods.

However, such ecologically urgent price developments entail negative and, above all, very unequally distributed income effects, which must not be neglected under any circumstances if one wants to organize political majorities for a transformation of the economy toward climate neutrality. It should be noted that the calculations presented here refer to the average net hourly wage or the average net hourly salary of a worker in Germany. Since the wage spread and thus the inequality of income distribution began to increase in the 1990s, there has not been such a significant reduction in the price of fuel measured in working hours for the low-paid since then as there was in the decades before. For those in the upper income brackets, on the other hand, this trend has been all the more pronounced; their labor requirements to obtain large quantities of fuel are much lower than the figures cited above. Accordingly, they can be wasteful with this commodity despite all the taxes levied on it to date – and they have been doing so for years, as evidenced, for example, by the rising share of SUVs in new car registrations.

… but not feasible without compensation for the lower income groups

The answer to the economic and social problems arising for the poorer income groups from the price increases for fuels therefore lies in state redistribution and in wages. The state must cushion additional burdens on low earners through taxation and social policy, and the wage spread at the level of primary incomes must be curbed significantly and as quickly as possible. The envisaged increase in the minimum wage to 12 euros per hour is a step in the right direction, as it should put the wage structure at the lower end on an upward trajectory. A dynamic increase in the minimum wage and a citizen’s income that enables citizens in need to participate appropriately in social life are building blocks for cushioning the undesirable income effects of an ecologically intended increase in prices among the poorer strata of the population.

The decisive factor here is: Only the support of the individual allows to master the balancing act between the desired price-driven change in behavior by all and the socio-politically unacceptable reduction in the prosperity of the lower income groups. The individual, who is supposed to adapt but must not be overburdened with the adjustment effort. However, the climate is not served by the promotion of the demand for fuels, for example, by raising the commuter allowance, lowering the VAT rates on fuels or reducing CO2 taxes. This slows down the necessary adjustment process or eliminates it altogether. On top of that, the unequal distribution of the burden of adaptation is exacerbated by this kind of support. Those who hardly pay any income tax because of their low income will benefit much less from an increase in the commuter allowance than those who earn well. Those who cannot afford a long vacation or a large apartment because of their low income will benefit less from a reduced VAT on fossil fuels than rich long-distance travelers or residents of luxury homes.

The international dimension of the problem

But what our politicians must pay at least as much attention to: A price signaling strategy must start at the global level to be successful. A look at fuel prices in various European countries illustrates the problem: In Poland, the state levies an energy tax on gasoline of 37.4 cents per liter, about a third less than in Germany (65.45 cents), which leads to fuel tourism in the border region. In the Netherlands, on the other hand, the tax of 81.3 cents is around a quarter more than in this country. In the USA, driving a car is dirt cheap compared to Europe due to considerably lower taxation. Fundamentally changing this is likely to be even more difficult to implement in the USA than on this side of the Atlantic, if only because of the less dense local and long-distance public transport network.

Not to mention the protests of the auto industry on both sides of the Atlantic, which can use the killer argument of job losses if the price of individual transportation rises too high to gain the backing of politicians and large sections of the population at any time. How it is possible to complain at the same time, largely unchallenged, about a shortage of skilled workers and of workers in general in Germany remains a secret of the PR art of influential lobbyists.

No, as long as we seek to avoid a real increase in the price of fossil fuels instead of allowing it and, in parallel, compensating for the loss of income for poorer people, we will not come one step closer to a socially acceptable and thus democratically supported solution to the climate crisis with market-based instruments.