When European Monetary Union (EMU) was established more than 20 years ago, there was widespread hope that a large single European market, enhanced by a single currency and a single monetary policy, would make a significant contribution to permanently reducing unemployment in Europe. Things have turned out differently. High unemployment has taken root in Europe at least since the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, and it seems almost impossible to escape it.

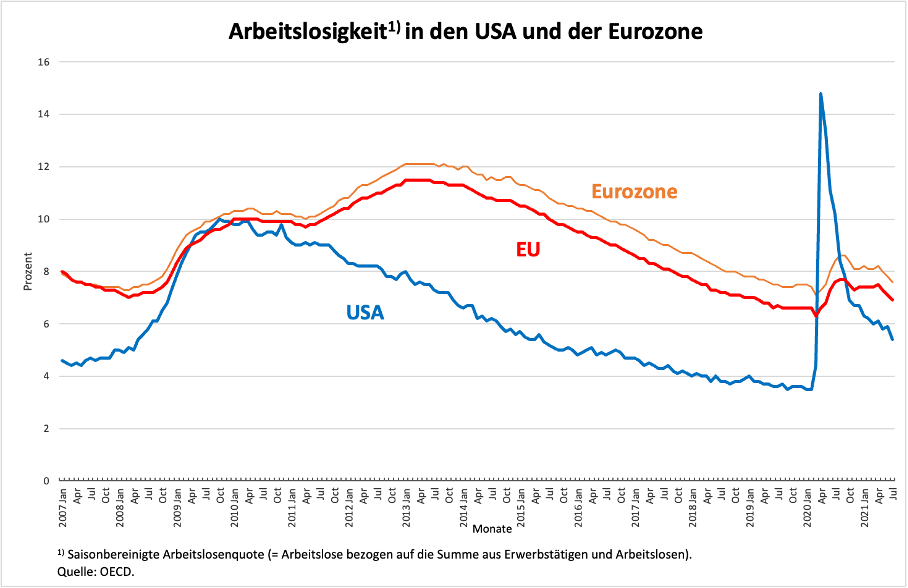

Even a simple comparison of the EMU with the U.S. in Figure 1 shows that the monetary union was far less successful than the U.S. in fighting unemployment after 2009. Although both regions had started from the same level after the 2008/2009 crisis, the U.S. reached a rate of 3.5 percent, which can be described as close to full employment, until shortly before the Corona crisis in February 2020. At the time, the eurozone recorded a figure of 7.4 percent, which was more than twice as high

Figure 1

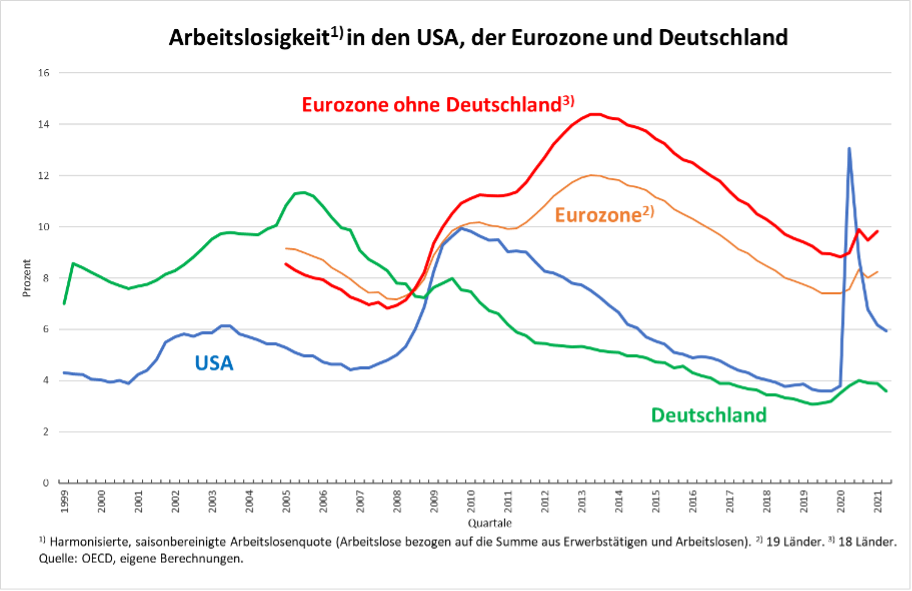

Europe is in an even worse position today if you remove from the calculation the country that is so immensely proud of its employment successes, namely Germany. Figure 2 shows that, excluding Germany, the eurozone, at 9.8 percent at last count (Q2 2021), remains at the level of unemployment it reached in the second quarter of 2009, just after the financial crisis.

Figure 2

What the figure does not show, however, is actual underemployment. This includes not only “open” unemployment but also, among other things, short-time work. This labor market policy instrument was used on a massive scale during the Corona crisis in Europe and in particular in Germany – in contrast to the USA. If we take into account this part of concealed unemployment, the German rate is currently well over 8 percent. The other countries in the monetary union would also have higher figures.

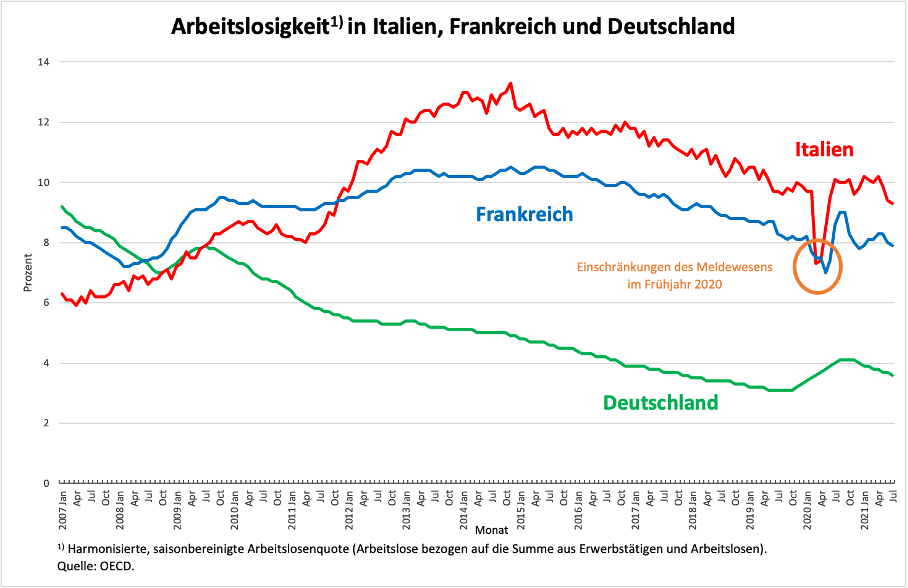

In other words, Europe is doing much worse than the USA. Unlike the U.S.A., if Germany is left out of the average analysis, Europe has never managed to significantly reduce unemployment after the financial crisis. As figure 3 shows, only Germany, thanks to its mercantilist strategy, which continues to have an impact on the real exchange rate today, was able to build up a low-wage sector at the expense of its currency partners, putting the labor market statistics in a favorable light and cushioning the inevitably parallel sluggish domestic demand with foreign surplus demand. Italy, in particular, is still well above the level it had reached before the financial crisis, but France has also reduced unemployment only slightly.

Figure 3

Surprisingly, this clear finding for Europe plays no role in the German election campaign. There is no opposition party accusing the government of having fundamentally failed here. One simply ignores the obvious connection that without Germany’s special role and without the failure of German economic policy, this finding would not exist. The political right blames Europe as such for the failure. And from the center to the left, there is in any case no economic policy concept for combating unemployment and, of course, there is no call in the media campaign theater to present one. The fact that a country that has joined a monetary union that aims to realize a single market cannot be successful in the long run without the partners in this union is not addressed. Instead, the consequences of Germany’s low-wage sector in the form of child and old-age poverty are discussed completely separately.

The high unemployment in countries like France, Italy or Spain and the lack of prospects, especially for young workers there, are not perceived as the downside of German economic policy. As a result, there is also no forward-looking policy with regard to the economic and political consequences for Germany. Not even climate protection, which is now constantly invoked by all democratic parties, seems to broaden the horizons of German politicians. For if already in Germany the solution of the social question is considered a prerequisite for successful climate protection, how much more must this apply to countries struggling with double the level of unemployment and more?

The central consideration…

To understand the crucial relationships means to turn to the empirical finding that already played the central role in my recent piece on inflation. The relationship between unit labor costs and inflation is also central to labor and unemployment because it shows that the signals attributed by the prevailing doctrine to a general reduction in wages do not exist for firms. Let us first consider a closed economy, i.e., the world.

A decline in nominal wages across the board can either immediately trigger a decline in demand, namely if prices do not fall at the same rate as wages. In that case, real wages will fall while employment initially remains unchanged, and private households will respond by reducing spending on consumer goods. This reduces the capacity utilization of companies and their profits, which, despite lower wages, then lay off workers who are not needed at a lower level of production.

In the medium and longer term, as the close correlation between unit labor costs and inflation shows, companies must expect to have to lower prices, so that the supposed advantage of lowering labor costs almost completely disappears again. Both falling demand in the short run and the prospect of falling prices in the longer run do not trigger the reactions expected by the prevailing neoclassical doctrine of a restructuring of production in the direction of higher labor intensity. Thus, wage reduction or wage restraint at the level of the entire world is clearly counterproductive in combating unemployment.

…and its “overcoming” on the level of the nation state

Any entrepreneur who tries to understand such considerations will immediately object that on his level, the level of the company, it is beneficial after all if wages fall, because he can then offer his products more cheaply, which gives him larger market shares and increasing profits. The same is true for all companies in a country: If wages and prices fall at the national level, it is to the advantage of all companies in the country if the exact same thing does not happen abroad. This is called a real devaluation or an improvement in competitiveness at the level of the nation. This kind of policy, which aims at job gains through wage sacrifice and at building external surpluses, has been called mercantilism some 200 years ago.

However, it is also obvious that the attempt of all countries in the world to improve their situation by lowering wages must fail. Either an appreciation of the domestic currency will compensate for the competitive advantage, or the other countries will react by increasing tariffs for the wage-reducing country, or sooner or later they will do the same, i.e. put pressure on domestic wages, which can only lead to global deflation, but cannot bring any improvement in terms of unemployment.

Only if the real devaluing country finds a niche in the sense that its trading partners’ hands are tied as far as devaluing its own currency and imposing tariffs are concerned, can it hope to benefit from going it alone even over a longer period of time. But even then, it will suffer in the long run if its trading partners pursue the same deflationary wage policy as it does, because this threatens the “world” scenario described above, where wage pressure leads to nothing but more unemployment.

Germany found exactly this niche when it exerted political pressure on wages under Red-Green in the early 2000s and, as a result, managed to devalue in real terms within EMU. It dramatically increased its export share of GDP and build up a huge current account surplus. At the same time, Germany has imposed an economic policy regime in EMU – and this is the great European paradox – which boils down to the fact that you can only be successful in fighting unemployment if you run current account surpluses. But this is precisely the path that Germany, with its early decision to move in this mercantilist direction, has blocked for everyone else.

Neoliberalism is not a European invention, but a German one

The fact that these issues are not even addressed in a German federal election campaign shows how far Germany has strayed into an untenable position across almost the entire political spectrum. The dominant parties in Germany have never wanted to acknowledge what is indisputable: the European area, which – like the U.S. – is a largely closed economy, needs a completely different set of policies than a small open economy. If Germany were to aggressively advocate this realization and its economic policy consequences in EMU, the entire European Union would be on a completely different course within a few weeks. Many countries have been waiting (in vain) for years for such thinking to finally prevail in Germany.

All those from the left and from the right who accuse the EU, the EMU and the European Commission of neoliberalism are addressing the wrong institution. European neoliberalism not only has German roots, but is German at its core because a German government that wanted to could eliminate it immediately. The European institutions were “converted” to neoliberalism by German politicians and diplomats behind the scenes in the 1980s, when Reagan, Thatcher and Kohl proclaimed the intellectual-moral turnaround, in a way that can only be called politically brutal.

This is deliberately ignored by all those who – for whatever reason – have chosen Europe as their supreme enemy. For them, the undeniable European neoliberalism offers a welcome target. It is declared, with all sorts of flimsy justifications, to be the natural accessory of an international organization, without wanting to understand that these organizations are always only faithful images of their most powerful members. European neoliberalism could be ended as early as the week after next if there were a German government coalition as of September 26 that set itself precisely that goal. Europhobia that focuses at Brussels or Frankfurt institutions without naming the real sources of neoliberalism is ridiculous and stupid.

The theoretical source of confusion runs deep

It is more than astonishing how difficult even left-wing or pro-union economists find it to criticize the mainstream on unemployment. They are still blinded by the notion that there could be such a thing as a labor market in which supply and demand reactions similar to those in simple goods markets are to be expected. The potato market analogy has often been criticized, but nevertheless union members and the economists who advise them keep acquiescing to the managerialist view rather than criticizing it aggressively and radically.

Wage levels must be a macroeconomic objective if economic policy is rational, and union leaders must present exactly this to the public if they want to be taken seriously. Any concession in the sense of the argument that companies are doing badly and therefore employees must also tighten their belts is out of place. If they tighten their belts, as they did last year and again this year because of the Corona shock, they will worsen the situation overall for employees and companies at the same time.

It is impossible to understand why union officials and left-wing economists are always at the forefront of warning the state against procyclical policies (policies that exacerbate the situation instead of improving it). But households respond in a procyclical manner as a matter of course when their revenues fall. If their revenues fall, they respond by reducing their spending. In the case of government, almost everyone criticizes such a reaction as procyclical. With wage policy, however, the logic is exactly the same. Since workers cannot be expected to reduce their savings rate when incomes fall, any wage cut or wage restraint is immediately as damaging to employment as an austerity drive by the state in the wake of lower revenues. In labor relations, a macroeconomic expenditure-revenue logic rules, not the microeconomic market logic of supply and demand.