One of the questions often asked is about the current accounts of a number of traditional European deficit countries. Some of them record surpluses today and people wonder if this is not a positive signal. Italy, which has turned its deficit into a meagre surplus, is an example. The argument that the European economy is improving because the current accounts deficits of some countries are decreasing is often made in the media. For example, Martin Sandbu made a lot of this in The Financial Times on 9 December 2015. But how does the deep recession in Europe fit into this picture? Did it influence the development of current accounts or not?

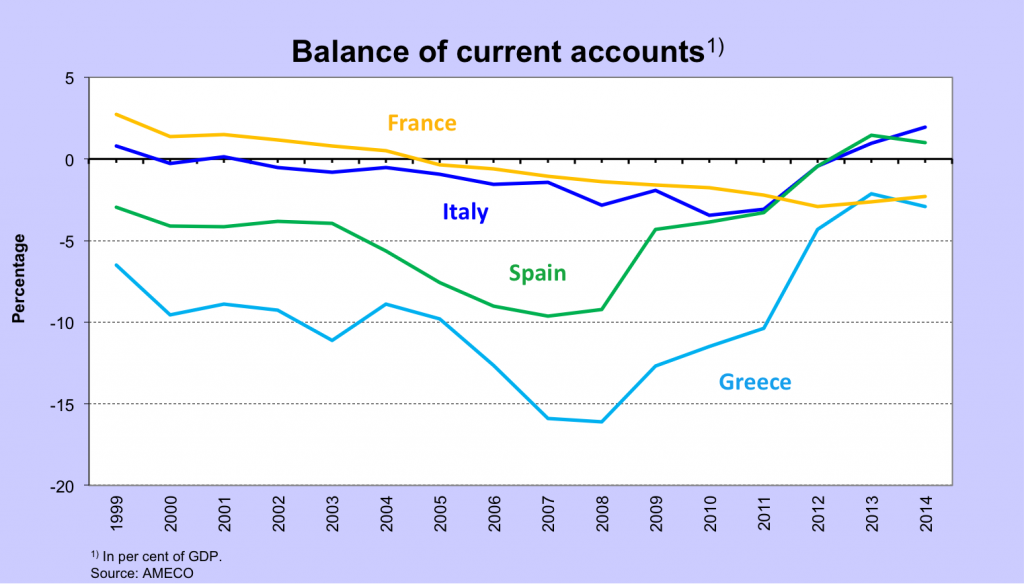

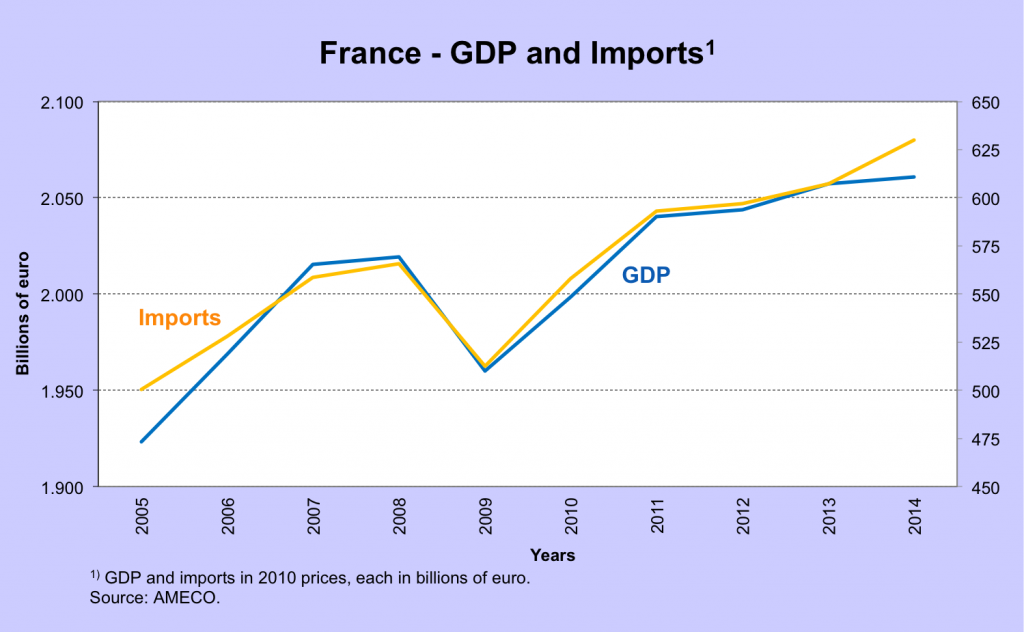

The fact that the trade balance depends to a very high degree on the level of economic development can be shown empirically. To do so, we look at the evolution of GDP and the evolution of imports in four countries, France, Italy, Spain and Greece. Each of these countries clearly slipped during the first years into a current account deficit. Figure 1 shows the evolution.

Figure 1.

The biggest changes in the current account occurred where the largest declines in economic activity took place, it is to say in Spain and Greece. Italy, which has been in a recession for years by now but without ending up in a major slump, is somewhere in the middle and in France, where economic activity plummeted the least, the current account changed only minimally.

Two of out of these four countries (Spain and Greece) made great efforts to overcome their crisis. Stringent neoclassical ‚structural reforms‘ were implemented. Strong downward pressure was put on wages. Labour markets were further ‚liberalised‘. We commented on this evolution many times in the past. In the two other countries, the same neoclassical policies were not implemented, or certainly not near anywhere to the same degree as in Spain or in Greece.

For all countries, one single feature stands out: imports very closely follow overall GDP. France shows an extremely close relationship between the evolution of GDP and the evolution of imports (we show this evolution on two scales for clarity’s sake). Both during the decline in 2009 and, later, during the weak upward movement, imports evolve in a way that is extremely similar to the evolution of GDP.

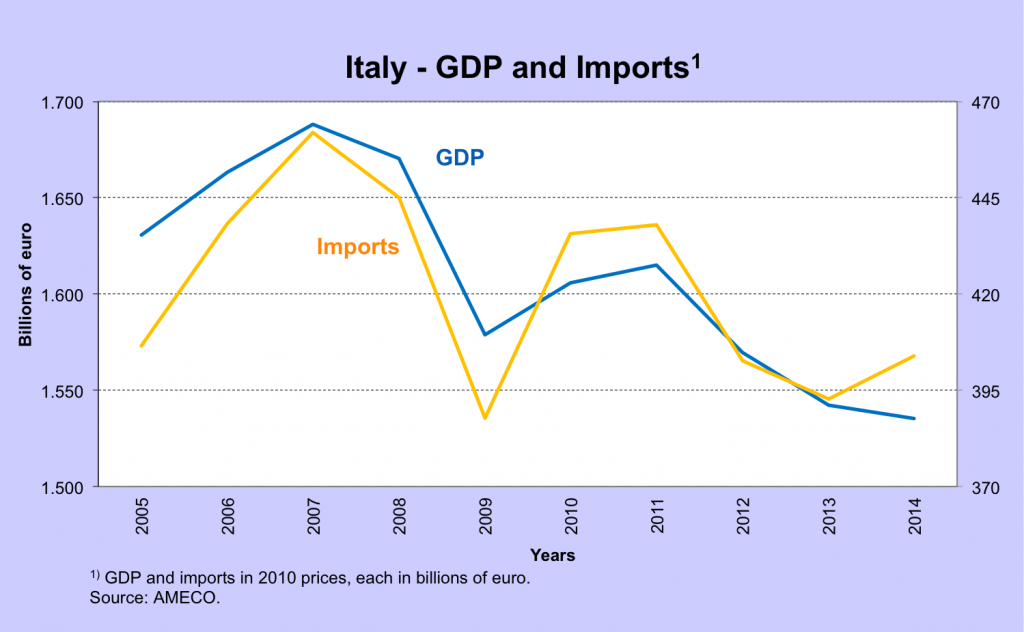

Figure 2.

The same close relationship can also be observed in Italy. In the course of the prolonged recession, imports fell substantially but, unlike France, after 2011 the country fell back into a recession.

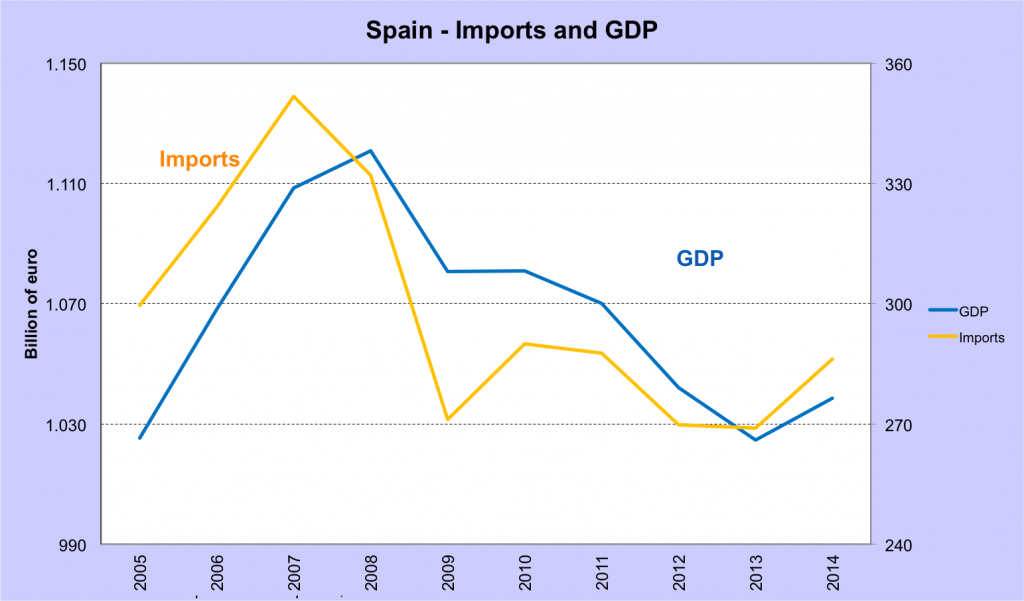

Figure 3.

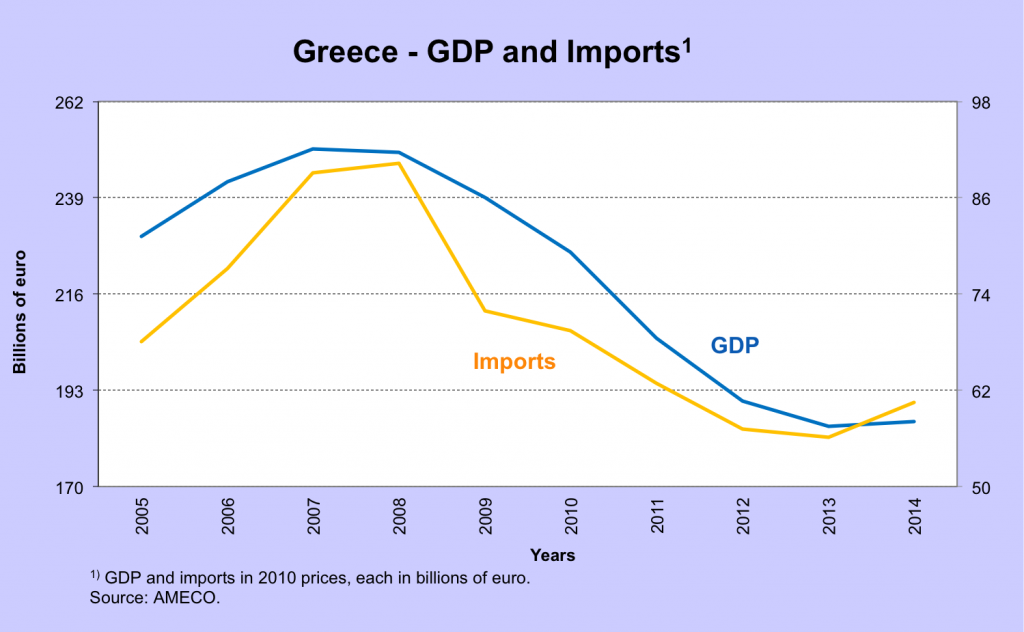

The situation is completely different in Spain and in Greece. The ‚reforms‘ were followed by an extremely deep slump in GDP, which was followed by a massive slump in imports.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

The relatively strong increase in current account balances in Italy, Spain and Greece (in this order from smallest to largest increase) exactly corresponds to the respective slump in economic activity in these countries. As to the question whether the adjustment programs have worked to turn the economy around, the answer is a definite no, but this is another story. But it is obvious that the evolution of the current account balance cannot be used as a valid indicator for an economic improvement.

These results perfectly reflect the logic that tells us that changes in current account balances occur either because of quantity adjustments or because of price adjustments; there is no other possibility. In the past (when economists where still thinking in a straightforward way!), people knew that such changes take place, either because of demand side expenditure reductions, this is lower demand caused by lower incomes, or because of switching of expenditure, which are changes in consumption behaviour that are triggered by changes in price. Adjustments in import volumes very much reflect changes in GDP. Adjustments in prices are usually triggered by wage adjustments or, in systems of variable monetary conditions, by changes in exchange rates (specifically real devaluations and depreciations).

It is really that simple and at the same time that difficult. Those who really want to change circumstances for the better in the deficit countries cannot rely on adjustments in quantity, but must instead rely on changes in prices. A shrinking GDP cannot be the goal of any rational policy. For nominal GDP to rise and to return to a normal growth trajectory without running into current account deficits again, expenditure switching induced by wage and price changes is indispensible. This is the truth about it, regardless of what second rate economists cook up about so-called price elasticies in exports and imports.